VOL. 3 EPISODE 4: AMERICAN EMPIRE

At the turn of the 20th century, America flexed its power globally and claimed a small empire. We tell the messy story of American imperialism and the ideas which shaped the process.

INTRODUCTION [0:00-02:06]

In 1897, future president Teddy Roosevelt reflected on the state of the Nation, “I should welcome almost any war,” he said, “for I think this country needs one.”1 Roosevelt did not have to wait long.

The following year, the US declared war on Spain. Roosevelt then resigned his position as Assistant Secretary of the Navy and became a national hero by leading a rag-tag cavalry unit in Cuba called the Rough Riders.2

Roosevelt was a unique individual, but his comments on war were actually quite normal for his day. There was something in the national mood, in the American zeitgeist, that welcomed, even craved, war. Many wanted new territory, others thought war would rejuvenate the Nation. Some, like Roosevelt, were motivated by both.

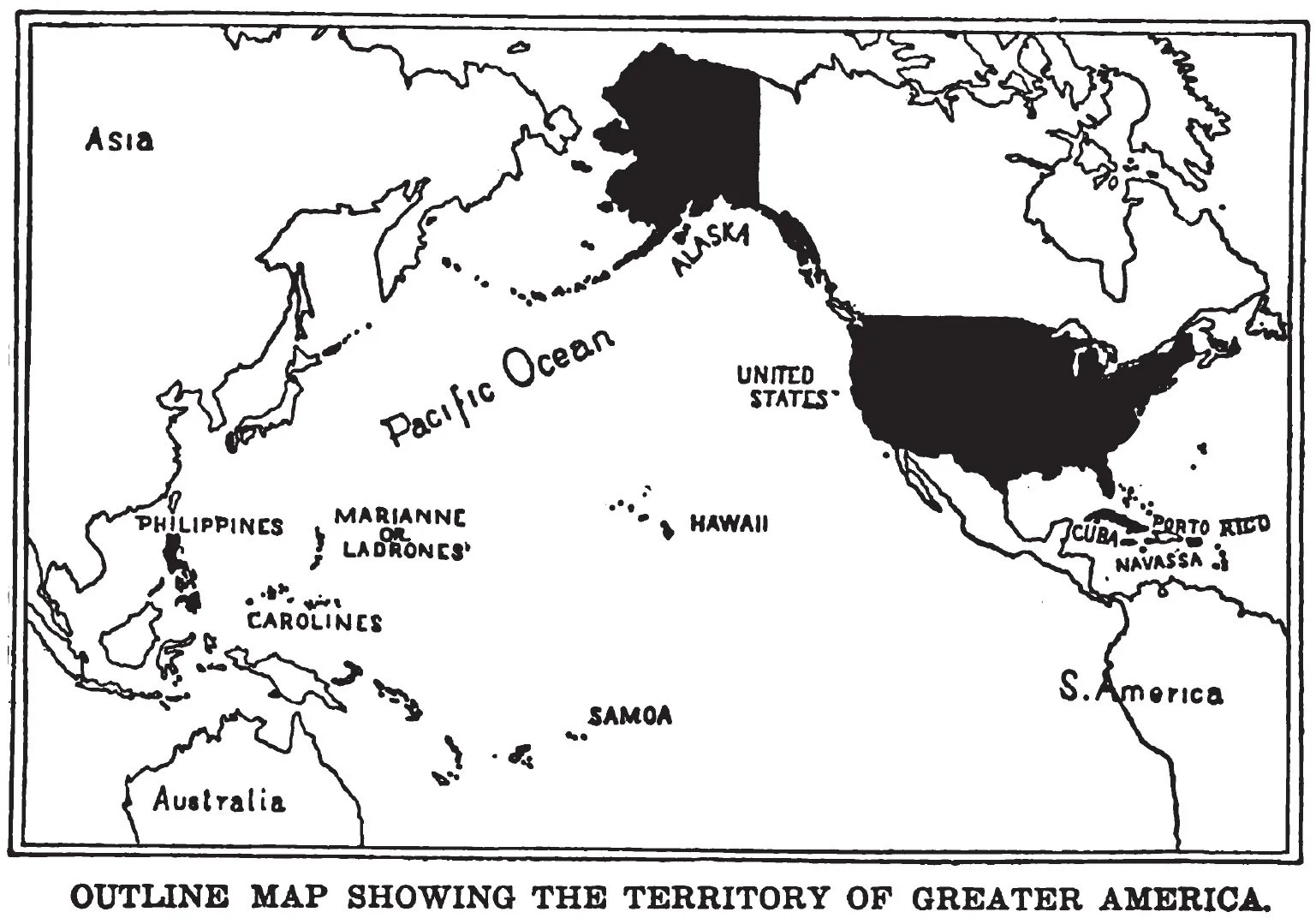

So, in the 1890s, the United States embraced an expansionist foreign policy that led to the acquisition of Hawaii, Cuba, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, Guam—and influence in Central America. The story of colonization also reveals the conflicting ideas Americans held about race, gender, civilization, economics, and religion.

American imperialism was filled with complexities, tensions, and contradictions.

Let’s dig in.

— Intro Music —

[Welcome to American History Remix, the podcast about the overlooked and underexplored parts of American history. We’re glad you’re here!]

BACKGROUND [02:06-04:10]

In 1796, in his farewell address to the Nation before retiring from office, George Washington offered the country a series of thoughts on how to preserve the republic. He reflected on the importance of religion, education, and morality among the people. He spoke of the dangers of regionalism and political parties. And he warned of the danger of foreign affairs. The relationship with other nations, particularly European nations, should be commercial. He argued that America should “have with them as little political connection as possible.”3

For a long time, the United States followed this advice. The policy was formalized in 1823 when President James Monroe issued his Monroe Doctrine—the United States would only concern itself with events in the Western Hemisphere.4

At the end of the century, the United States abandoned this policy of only engaging in continental affairs in favor of global imperialism. But why?

The period from the 1880s to the outbreak of WWI is called the “Age of Empire.” Imperialism is, of course, not new. But in this period, European nations competed with each other to claim areas around the globe, most especially in their “Scramble for Africa,” carving up and dividing regions of the continent among themselves. In Asia, China was weakened from war and internal conflicts, so Western nations moved in and claimed territory there as well.5 American imperialism is, therefore, part of a global story.

HAWAII [04:10-08:30]

The first signs of the change in policy came in Hawaii.

The remote islands of Hawaii, sitting in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, were settled by Polynesian explorers in the 4th century CE and united into one kingdom in the early 1800s.6

US involvement in Hawaii was not led by the government or military—they came later. Missionaries and merchants led the way.

Christian missionaries from the US arrived on the islands in the 1820s. They helped convert Native Hawaiians to Christianity and established churches, schools, and newspapers. American merchants came too. They traded for local resources and used the islands to facilitate trade with Asia.7

Mission school children, Lahaina, Maui, Hawaii. Internet Archive Book Images, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons.

But the two groups had conflicting goals. Merchants were frustrated with missionaries because their work interfered with local trade. Every day spent in church or school was a day not spent harvesting resources. One merchant remarked that business on the islands would surely grow, “if not for these canting missionaries.” Likewise, Reverend William Ellis referred to white merchants as an “enemy.”8

However, in the 1830s, the distinction between the two groups began to blur. An economic depression made businesses more desperate to extract wealth from the islands and also undercut missionary funding. Both groups then sought more economic control of the islands.9

Missionaries supplemented their income by establishing their own sugar plantations. They also pressured the chiefs to enact land reforms, which allowed for private rather than communal land ownership. Once these were enacted, even more foreigners were able to buy land.10

Native Hawaiians largely adapted to Western ways. Most converted to Christianity, embraced ideas of a representative government, and instituted the land reforms Westerners wanted. They hoped to demonstrate their civilized culture, legitimacy, and right to remain a sovereign nation in the face of imperialism. For a while, the method worked. France, Great Britain, and the US all recognized Hawaii’s right to remain an independent kingdom.11

However, Hawaiian westernization had unintended consequences. With the land reforms, more Americans were able to establish plantations and expand Hawaii’s commercial agriculture. And an 1875 treaty allowed Hawaii to export sugar to the US duty free, further tying the kingdom to the United States. As plantation owners brought in outside laborers, Native Hawaiians succumbed to disease. By 1890, Hawaiians made up less than half of the islands’ population.12

Though on paper Hawaii was a constitutional monarchy with a representative legislature, the rights of Natives were limited, and American merchants, planters, and the children of missionaries came to dominate politics. Voting was a privilege reserved for landowners. Native Hawaiians without land could not vote. Foreign citizens with land, like a sugar plantation, could vote.13 Several Americans even served as Hawaiian diplomats to America.

Thus, American missionaries and merchants began the informal colonization of Hawaii.14

BAYONET CONSTITUTION & COUP [08:30-11:50]

However, they still shared political power with the monarchy, and they were hungry for more.

In 1887, to strengthen their hold on the kingdom, a mostly Caucasian force wrote a new constitution, which gave greater power to the legislature (which they controlled) and reduced the power of the king. They marched into the royal palace and forced King Kalakaua to sign the document under threat of violence. With no real choice, he obliged. It became known as the Bayonet Constitution.15 Though still an independent kingdom, the Hawaiian government was in the hands of Americans.

But in the early 1890s, two events threatened that control. First, in 1890, the US eliminated the tax-free import of Hawaiian sugar, seriously threatening the profits of sugar planters. But… the planters were clever. No one would need to pay a tax to import goods to America if Hawaii was part of America….16

Second, Queen Liliuokalani ascended to the throne in 1891. Beloved by her people, she sought to restore power to the monarchy, resisted American influence, and fostered Hawaiian nationalism. Her goal was “Hawaii for the Hawaiians.”17

Signed photograph of Liliuokalani, the last sovereign of the Hawaiian kingdom, c. 1891. See file page for creator info, via Wikimedia Commons.

The solution to both problems was the same—the American annexation of Hawaii.

Lorrin Thurston and Sanford Dole, both the children of missionaries, led the way. They formed a secret organization called the Annexation Club. Thurston even visited Washington DC in the spring of 1892 and privately met with several members of President Benjamin Harrison’s administration, fostering support for Hawaii’s annexation.18

In 1893, the Queen made her move and revoked the Bayonet Constitution. The Annexation Club responded by staging a coup, removing the Queen from power, and establishing their control of the islands as the Committee of Public Safety.19 They then asked the US government for assistance. The American Navy showed up and helped secure the committee’s power and the overthrow of the Hawaiian government.20

Raising American Flag at United States Annexation Ceremony at ʻIolani Palace, Honolulu, Hawaii. Frank Davey, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

America, however, did not rush to annex the islands. Newly elected President Grover Cleveland opposed annexation, and Congress only recognized a new Hawaiian Republic. That’s where things sat until the end of the decade.21

CAPITALISM & CHRISTIANITY [11:50-16:48]

In the story so far, we’ve seen a fascinating process: the intermingling of Christianity with capitalism.

Proponents of imperialism saw Christianity and capitalism as united, nearly synonymous.

Minister Josiah Strong published Our Country in 1890. The book offered a robust and multifaceted argument that the United States ought to take a role in converting and civilizing the world. In Strong's mind, civilization depended on conversion to Christianity, capitalism would then follow suit, but only when a native population grew dissatisfied with its material conditions. That is, to want more things and desire wealth. This line of thought permeates his book. “What is the process of civilization but the creating of more and higher wants?” Elsewhere he said, “The millions of Africa and Asia are someday to have the wants of a Christian civilization.” Finally, “Men rise in the scale of civilization only as their wants rise.”22

In 1896, educator Merrill Gates reflected on Native American civility. “To bring him out of savagery into citizenship we must make the Indian more intelligently selfish.” The author went on: “We need to awaken in him wants. In his dull savagery he must be touched by the wings of the divine angel of discontent.” Discontent was needed “to get the Indian out of the blanket and into trousers, —and trousers with a pocket in them, and a pocket that aches to be filled with dollars!”23

Future president William Howard Taft claimed that modern civilization was driven by “the right of property and the motive of accumulation.”24

These ideas go back to economist Adam Smith, who argued that rational self-interest was the engine of economic progress. As men want more, they purchase more. As demand goes up, production likewise increases. As businessmen, pursuing their own interests, compete with each other, they naturally adapt and innovate. Since the origins of capitalism in the 1700s, self-interest has come to be seen as a universal economic law.25

Christianity, capitalism, and civilization were, in the minds of Americans, all united forces.

But…this had little to do with traditional Christian ethics. Biblical authors referred to “wants” and “self-interest” as greed and covetousness. “Thou shall not covet” is one of the Ten Commandments.26 The Apostle Paul referred to covetousness as idolatry—that is the worshiping a false god.27 Jesus didn’t tell his followers to seek wealth. Instead, he said how hard it was for the wealthy to enter the kingdom of God. He said you cannot serve both God and money.28

In the Reformation, Protestant reformers like Martin Luther and John Calvin argued that economics must be subservient to ethics and theology. They spoke against selling goods at the highest price they could bear as well as charging interest for a loan. Economics, in their view, should be less about production, and more about fair distribution.29 Luther argued that economics should not be governed by self-interest but by benevolence.30

American Christians in the 19th century, however, flipped traditional Christian ethics inside out and equated greed with godliness and self-interest with God’s divine plan.31 It is both fascinating and bizarre.

AMERICA & CUBA [16:48-21:08]

The next step in American imperialism came in the Spanish American War, and the conflict with Spain began in Cuba.

A colony in the Spanish Empire, Cuba had long struggled to gain its independence. From 1868-1878, revolutionaries fought to overthrow Spanish rule, but the revolution was put down. Cubans tried again from 1879-1880 but remained a colony of Spain.32

Then, in 1894, American tariffs on Cuban goods hurt the island economically and contributed to further social unrest. The following year, José Martí, an exiled poet and revolutionary, returned to Cuba from the US to lead yet another war for Cuban independence.33

Antonio Maceo's cavalry charge during the Battle of Ceja del Negro, October 4, 1896. Jorge Wejebe Cobo, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The Spanish sent 190,000 soldiers to put down the rebellion. Fighting a war of attrition, Martí adopted a scorched earth policy—destroy everything and force the Spanish to leave the island. The Spanish responded with their own brutality. They rounded up nearly half a million civilians whom they believed were aiding the revolutionaries and forced them into detention centers, where 95,000 people died from malnutrition and disease. Cuban fighters responded by slaughtering Spanish soldiers—about 35,000 a year and, in the words of one historian, “littering the sugar and pineapple fields with the heads of Spanish soldiers.”34

The US had strong economic ties to Cuba. American businesses owned sugar plantations and ranches on the island. 87% of Cuban exports went to the US. Given the geographic and economic proximity, Americans were sympathetic to the Revolution. However, direct US involvement did not materialize right away. Some Cubans welcomed the potential of US aid, others feared that American intervention would mean the US would take control. “To change masters is not to be free,” Martí reflected.35

Republican President William McKinley, elected in 1896, embraced an expansionist platform and believed America should increase its influence in the world. He spent two years negotiating with Spain. After years of fighting, Spanish forces were greatly depleted. Spain, however, was still reluctant to grant Cuban independence.36

Then, in February of 1898, the New York World newspaper published a private letter written by Enrique Dupuy de Lome, the Spanish Minister to the US. In the letter, the minister called President McKinley weak, he simply followed the opinions of the crowd and wasn’t a true leader. The comments were nothing that Americans weren’t already saying. Teddy Roosevelt claimed McKinley had “no more backbone than a chocolate éclair.”37 But such an insult from a foreign minister was an insult to the whole nation, and the public grew angry.

Meanwhile, sensationalist newspapers, dubbed the “yellow press,” published stories about Spanish brutality. The yellow press often gets credit for inflaming the public and its support for intervention in Cuba. But support for the war was popular even in areas where the press did not circulate their papers. Other, deeper sentiments were at play.38

WAR & GENDER [21:08-24:46]

As America grew in size and population, modernized, and industrialized, the American people held a special pride in their country’s “progress.”39

But there was another side to this. Some feared that the comforts of civilization were making men soft. “Over-sentimentality,” said Teddy Roosevelt, “over-softness, in fact washiness and mushiness are the greatest dangers of this age and of this people.”40 Hence his comments about needing a war.

Senator Henry Cabot Lodge saw a similar problem. Anglo American men were, in his view, endowed with innate abilities, which he described as “an unconquerable energy, a very great initiative, an absolute empire over self.” But material comforts were distracting men. Wealth, comfort, and soft white-collar jobs threatened a man’s vitality.41

Furthermore, early 19th century Americans conceptualized the world as existing in separate spheres. Men occupied the public sphere of work and politics, while women remained in the private world of home and family.

By the end of the century, that division was seriously challenged. Though they did not yet possess the national right to vote, four states granted women full voting rights in 1896, and twenty-one others allowed women to vote on local issues. Women participated in politics in other ways too. They formed political organizations, attended rallies, and campaigned for candidates.42

Women also joined the workforce in greater numbers. If they were financially able, they attended college, rode bicycles, and participated in social reform movements.43

To older men, the public prominence of women in their realm was unsettling. Likewise, an economic depression in 1893 made it harder for men to provide for their families. It was yet another threat to American manhood.44

The combination of national pride mixed with anxiety over the country’s waning manliness created an atmosphere where many men embraced aggression and war. We call it jingoism. It was a sentiment akin to nationalism. It was aggressive, uncritical patriotism which saw war as a means to national glory.45

Jingoes came from a variety of backgrounds—young and old, upper and lower class. But they were united in their belief that war would strengthen the character of American men. The country, they believed, was becoming effeminate, and war was the antidote. “No greater danger could befall civilization than the disappearance of the warlike spirit…among civilized men,” remarked naval officer Alfred Thayer Mahan.46

And the Jingoes got their way. Let’s return to Cuba.

THE USS MAINE [24:46-27:11]

The American government, concerned about its citizens in Cuba amidst the fighting, sent a battleship called the USS Maine to Havana. While in the port, on the night of February 15th, 1898, the ship suddenly exploded. 266 men died, and the wreckage sank into the sea. The yellow press immediately blamed the Spanish. Who else would have done it?47 The public went wild.

Explosion of the American battleship Maine, February 15, 1898. Fouquet at nl.wikipedia, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

“Remember the Maine, to Hell with Spain,” became the rallying cry. Spain refused to apologize and suggested that the explosion was actually caused by the sailors themselves. That just pissed off the public even more.48

Again, Americans understood the events in terms of gender. Spanish action—real or imaginary—was an affront to American manliness. America must respond. As one senator at the time claimed, “American manhood and American chivalry give back the answer that innocent blood shall be avenged.”49

Even congressmen who were reluctant to go to war understood the events in terms of honor and manliness. “Better far that this war should come… than the degradation of our country’s honor.”50

President McKinley asked Congress for authority to intervene in Cuba, and Congress granted it. The Spanish American War had begun.51

…. But here’s the thing: the Spanish didn’t blow up the USS Maine. Subsequent investigations revealed that the most likely cause was a coal chute fire, which spread to the armory and exploded. In other words, it was a freak accident, which occurred at the worst possible moment. Unless you were a Jingo and wanted a war… then it was great.52

SPANISH AMERICAN WAR [27:11-29:38]

The Spanish American War itself is often either overlooked or mythologized. The US Navy defeated the Spanish fleet in Santiago Bay and thereby cut off supplies to Spanish soldiers. American forces then moved inland. The Spanish fought hard, but after three years of war with Cuban revolutionaries, they were worn out. The Spanish American War lasted only four months, and less than 400 American soldiers died in combat. US Ambassador John Hay called it a “splendid little war.”53

But a closer look reveals it wasn’t quite as “splendid” as it appeared. General William Shafter, the commander of the invasion, weighed over 300 pounds and required a contraption of ropes and pulleys just to mount his horse. Not a very inspiring image. Meanwhile, volunteer soldiers were often unprepared for combat. The camps were crowded and dirty, and men complained that the food made them nauseous. Five thousand American soldiers died from disease.54

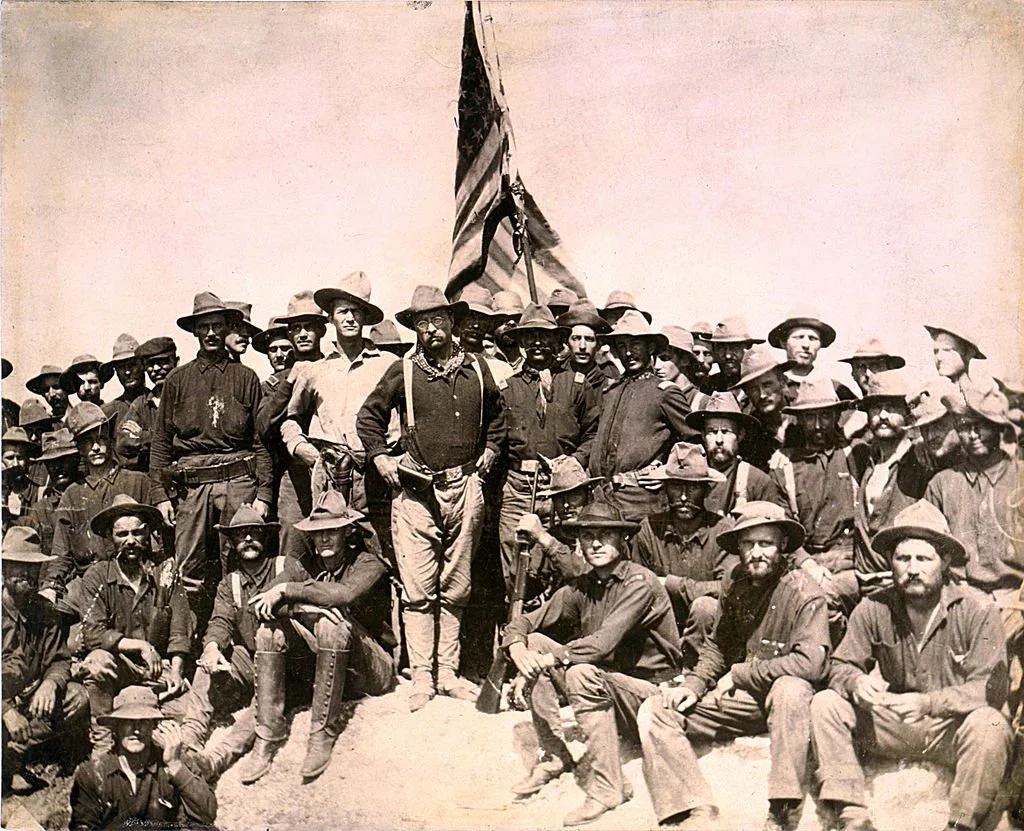

Teddy Roosevelt, however, emerged from the war as an American hero. As we said before, when the war broke out, he was serving as the Assistant Secretary of the Navy but resigned his position to form the Rough Riders and departed for Cuba. He famously led his men to take Kettle Hill, despite moving uphill into Spanish gunfire.55

“Colonel Roosevelt and his Rough Riders at the top of the hill which they captured, Battle of San Juan.” William Dinwiddie, photographer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Roosevelt long saw war as beneficial to the Nation. War, he believed, produced strong leaders, manly men who could best govern the Nation.56

He was partly right. Capitalizing on his success in the war, he won the governorship of New York in 1900, then became McKinley’s vice president, and then president himself.57

So, this romanticized but forgotten war had long-lasting impact on American politics. But there is still more to the story….

SEIZING TERRITORY [29:38-33:11]

The first battle of the Spanish American War actually occurred in the Philippines. For those listeners who struggle with geography, Cuba is just south of Florida. The Philippines are 9700 miles away in the Pacific Ocean. They’re an archipelago of over 7000 islands which, at the time, was a Spanish colony.58

Like in Cuba, locals challenged Spanish rule. A few years prior, Emilio Aguinaldo led a nationalist revolt against Spain. But it was unsuccessful, and he was forced into exile in Hong Kong.59

When the war with Spain began, the US saw an opportunity. Before resigning from the Navy, Roosevelt ordered Admiral George Dewey to attack the Spanish in the Philippines. Dewey destroyed the Spanish fleet stationed in Manila Bay without losing a single American life.60

President McKinley then looked to Hawaii. He actually wanted to annex Hawaii ever since he assumed office, but Congress was still unwilling to annex the Republic. The capture of the Philippines changed the situation. Hawaii would be a strategic location between the Philippines and the American west coast. And so, Congress approved Hawaiian annexation in July 1898. Native Hawaiians protested that they were not consulted, non-Natives cheered.61

McKinley also ordered the Navy to seize Guam, located between Hawaii and the Philippines. It was another strategic location also belonging to the Spanish. The island was (and still is) isolated. So, when American forces arrived in June of 1898, the Spaniards stationed there didn’t even know the nations were at war…. they were quickly captured.

The US then took control of Wake Island, hoping it could be used to establish cable communications in the region. Germany had claimed it, but they gave up the uninhabited island without a fight.62

Back in the Caribbean, the US also wanted to capture Puerto Rico, yet another Spanish colony. But quick success in Cuba presented a challenge. The US needed to take Puerto Rico before the Spanish could sue for peace. McKinley gave orders to invade the island as soon as Cuba was secure. American forces arrived on July 25, 1898 and were welcomed by most Puerto Ricans. Just two weeks later, Spain was ready to end the war altogether.63

The United States and Spain agreed to terms in the winter of 1898. The treaty ceded Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines to the US. Cuba, however, would become independent…sort of.64

CUBA INDEPENDENT? [33:11-34:52]

During the Cuban Revolution, the American press highlighted the brutality of the Spanish and overlooked the atrocities committed by Cuban revolutionaries. There were clear good guys and bad guys.65

But after America joined the war, the narrative shifted. The press portrayed Cuban forces as cowardly and unmanly. They overlooked how the war had devastated the island and simply portrayed it as underdeveloped and backwards. Likewise, they ignored the fact that Cuban forces actually cleared the way for American troops.66

America’s official policy towards Cuba shifted as well. Shortly after entering the war, Congress passed the Teller Amendment, stating that the US supported Cuban independence. They would not annex Cuba. But, in 1901, nearly three years after the Spanish American War ended, Congress passed the Platt Amendment which ensured that the US would control a naval base in Cuba—Guantanamo Bay. It also gave the US the right to intervene in Cuba as it saw fit. With independence on the line, the Cuban government essentially had no choice but to add the amendment to their constitution. It essentially made Cuba a protectorate of the United States.67

THE PHILIPPINES [34:52-37:03]

The situation in the Philippines wasn’t any better.

Like in Cuba, Filipinos had been fighting for their own independence from Spanish rule. Would America now withdraw its troops and allow for Philippine independence? No.68

For one, Americans viewed Filipinos as racially inferior. They regarded them as “savages” and animal-like. Withdrawing American troops from the nation would, according to one senator, lead to “loot, pillage, and rape.”69

Gender was another justification. Filipinos, many Americans argued, were effeminate. They claimed Filipino men did not work and were dependent on their wives. “These are not men,” wrote one American observer.70

President McKinley claimed he never wanted the Philippines; they simply fell into his lap during the fight with Spain. He said he was at first unsure what to do with them. But ultimately, he came to a series of realizations. First, he said, “we could not give them back to Spain—that would be cowardly and dishonorable.” Second, he could not give them to another empire, such as France or Germany, because “that would be bad business and discreditable.” Thirdly, he could not withdraw because “they were unfit for self-government.” Finally, he resolved that “there was nothing left for us to do but to take them all, and to educate the Filipinos, and uplift and civilize and Christianize them.”71

Honor, religion, economics, as well as racial and cultural prejudice all shaped the decision to keep the Philippines as an American colony.

RACE & CIVILIZATION [37:03-39:52]

McKinley’s explanation for taking the Philippines reveals another trend in American thought.

Many Anglo-American intellectuals at the time ranked human societies into a hierarchy. All human history flowed along the lines of progress, from lower forms of society to higher ones, with their own modern society being the highest.

As one author at the time put it, “It can now be assured upon convincing evidence that savagery preceded barbarism in all the tribe of mankind as barbarism is known to have preceded civilization. The history of the human race is one in source, one in experience, and in progress.”72

Often terms like “civilization” and “savagery” were poorly defined. But in 1877, Lewis Henry Morgan published Ancient Society, a book which divided societies into seven categories and arranged them into an imagined order of progress. There was lower, middle, and upper savagery; followed by lower, middle, and upper barbarism; then finally, a true civilization. According to Morgan, a lower savage society would fish and have fire. Middle savagery included the use of the bow and arrow. An upper savage society would develop pottery. And so on. Finally, civilization commenced with the phonetic alphabet.73

With such clear lines of development and progress, a modern “savage” society offered Anglo Americans a window into the distant past.74 Visiting a “savage” society in Asia or Africa was akin to traveling backwards in time.

In this view, the hierarchies between peoples and societies were cultural and therefore not permanent. Anglo Americans had simply progressed the furthest. But lower forms of society could be educated by higher forms. Hence McKinley’s argument to take the Philippines and civilize them. This perspective was also self-congratulatory. Anglo Americans could feel very comfortable sitting atop their invented chart of human progress while nobly taking lesser societies under their wings.

Or so the argument went.

PHILIPPINE AMERICAN WAR [39:52-43:21]

How then, did this play out in the Philippines? The situation on the ground was messy.

In 1898, the US had helped the exiled Emilio Aguinaldo return to the Philippines, believing he would help undermine Spanish control. Aguinaldo soon declared the Islands were an independent country and set up a “provisional dictatorship,” with himself as the head. The US, however, refused to recognize his government.75

Fighting broke out between American and Filipino forces in February of 1899. Thus, the Cuban American war gave birth to the Philippine American war.76

“Waiting for the word to advance,” the Philippine insurrection, 1899. Rockett, Perley Fremont, photographer. Miscellaneous Items in High Demand, PPOC, Library of Congress, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Aguinaldo had drawn many educated Filipinos to himself, but Americans also found Filipinos willing to aid them as scouts and guides. With local help, American forces were able to find and capture Aguinaldo in the spring of 1901. He then encouraged cooperation with Americans, but fighting continued…and it was brutal.77

Filipino forces conducted guerrilla warfare. The US then, unable to find their enemy in the open field, turned to the same tactics Spain had used in Cuba. They burnt down villages and forced civilians into concentration camps.78

In 1901, Filipino forces ambushed and killed about 50 soldiers on the Island of Samar. Americans responded by killing nearly all the inhabitants of the town of Balangiga. The US general who oversaw the fighting ordered his soldiers to kill every male over 10 years old.79

American forces also turned to torture, specifically a method called the “water cure.” Captured Filipinos were placed under a faucet with a stick in their mouth and forced to drink water until their bellies swelled. When that was insufficient, captives would have salt water injected up their nose.80

By the summer of 1902, resistance had quelled enough that Teddy Roosevelt, now serving as president, declared the war to be over. In reality, violent local resistance continued until 1912. Controlling an archipelago of 7000 islands was no easy task.81

During the war, the US lost 4000 lives, and another 2800 were wounded.82 Exact numbers for the Filipinos are hard to estimate. Perhaps 20,000 died in combat. At least 200,000 civilians died from the destruction the war brought to the land. Other estimates suggest perhaps 500,000-600,000 civilians died.83

ANTI-IMPERIALIST RESPONSE [43:21-48:05]

The Philippine-American War caused an intense national debate. Not all Americans were caught up in the expansionist fervor. Economics, national values, and race could both “justify” American imperialism and attack it.

Industrialist Andrew Carnegie warned that the islands would drain American wealth. Others feared that it would create competition and hurt American farmers.84

Some saw imperialism as anti-American and a betrayal of the American value of democracy. Philosopher William James dismissed the idea that the US was civilizing and “uplifting” Filipinos. He was shocked that America could, in his own words “puke up its ancient soul…in five minutes without a wink of squeamishness.”85

As we covered before, some thought the hierarchies between people groups was cultural and other societies could be educated and “lifted up.” That was McKinley’s argument.

But not everyone felt that way. Just as McKinley cited race as justification for seizing the Philippines, anti-imperialists cited race as a reason to give up the islands. Some believed race was deterministic and no amount of education or guidance could “uplift” certain populations. In the 1870s, John Fiske argued, “The capacity of progress…is by no means shared alike by all races.” He went on to elaborate, “Small-brained races…appear almost wholly incapable of progress, even under the guidance of higher races.”86

School Begins by Louis Dalrymple, Puck Magazine, January 25, 1899. Louis Dalrymple, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

According to this view, a race’s “innate” capacity determined its potential “progress.” Some features of a people group could not be overcome, and progress was therefore not inevitable.

Furthermore, some anti-imperialists argued that America was a white man’s nation. Its population should not be diluted with “debased and ignorant people,” as one contemporary described it.87

The cultural and racial views of society both had their adherents. In the late 1800s, most Americans tended towards the cultural view that the world could be educated and civilized. But the view that a race’s “innate” capacity determined its potential “progress” gained popularity in the early 1900s.

What’s more, many worried that America’s racial superiority was insecure. Eugenicist Madison Grant wrote The Passing of the Great Race in 1916. Grant argued that “Moral, intellectual, and spiritual attributes are as persistent as physical characters and are transmitted substantially unchanged from generation to generation.”88

The mixing of different races, Grant claimed, devolved to the lower form. “The cross between a white man and a negro is a negro; the cross between a white man and a Hindu is a Hindu.” This spelled trouble for America. Rather than saving the world, it was threatened by it. The millions of immigrants coming to the country were “the weak, the broken, and the mentally crippled of all races.” They were going to dilute the American character and overrun the Nation.89

American superiority was therefore fragile. National pride turned to national anxiety. This change in general attitude helps explain why in the late 1800s America claimed several colonies, but in the 1920s America more or less shut down immigration to the country.

COLONIES TODAY [48:05-49:40]

Management of America’s new colonies did not follow a single track. In fact, there was not a centralized office or department to oversee the territories. Instead, they each fell under a different government department. New Mexico and Arizona were also territories at the time, and they became states in 1912. The territories of Alaska and Hawaii, however, eventually became states, but remained for a long time under the oversight of the Department of the Interior. Puerto Rico and the Philippines fell under the War Department. Guam and Samoa under the Navy.90

The different paths help explain the different statuses of the territories today. The Philippines gained their independence in 1946. Alaska and Hawaii were granted statehood in 1959. Puerto Ricans today are US citizens and subject to American laws. They elect no senators but do send a member to the House of Representatives. That member, however, cannot vote.91

Map of "Greater America," 1899. Printed in War in the Philippines by Marshall Everet. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

PANAMA [49:40-52:49]

After the acquisition of these territories, American expansionism cooled. Rather than going to war and taking land, American intervention became more sporadic, but the Nation still showed a willingness to engage in international affairs. The prime example is Panama.

American and European nations had been interested in constructing a canal through Central America for decades. Particularly in modern Panama or Nicaragua, where the continent was narrow. A canal through the region would eliminate the need to sail around South America and increase access to the Pacific.94

French engineers had actually attempted to build a canal in Panama in the 1880s. The initial plan failed, but some Frenchmen remained in the region into the early 1900s. Panama, however, was not yet Panama. It was then part of Columbia, though it had fought several unsuccessful revolutions for independence.95

In 1903, the US offered a deal to Columbia. The US would build the canal and would gain a 100-year lease to a 10-mile-wide canal zone. Columbia would receive $10 million upfront and an annual payment of $250,000 for the duration of the lease.96

Columbia, however, knowing the true value of such a project, rejected the deal. They wanted more money. President Roosevelt was pissed. He called Columbian leadership “contemptible little creatures.”97

A satirical political cartoon reflecting America's imperial ambitions following victory in the Spanish American War of 1898. Victor Gillam, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

It was here the Panamanians saw an opportunity for their independence. Roosevelt and his Secretary of State secretly coordinated with a French official in the region and indicated that if the Panamanians revolted again, the US would not stand in their way—wink, wink. So, when they revolted in 1903, the US quickly recognized Panama as an independent nation, sent in warships to prevent Columbia from intervening, and the new country agreed to the deal the US had previously offered Columbia.98

The canal took ten years to construct, and it is an engineering marvel—it’s a canal through a continent. It facilitated quicker trade and contributed to a global economy. Panama, however, soon resented the deal. A canal through their country was their most valuable asset, and they sold it for much less than they could have.99

WESTWARD EXPANSION [52:49-55:52]

This brings us to our final theme—westward expansion.

It’s not a coincidence that America expanded overseas in the late 1800s, just as it finished settling the western reaches of the continent.100

In the 1800s, Americans generally believed it was their nation’s manifest destiny to expand across the continent. At the end of the century, once they’d run out of frontier, imperialists used the exact same language to describe expansion in the Pacific. President McKinley said, “We need Hawaii as much as in its day we needed California. It was Manifest Destiny.”101

A New Map of Texas, Oregon, and California, with the Regions Adjoining, 1846. Samuel Augustus Mitchell, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Under the Monroe Doctrine, the US had stayed out of European affairs. But lest we think that meant peace, the country engaged in continual warfare throughout the 1800s, as it conquered the West.

The Indian Wars, in fact, provided the US experience in subjugating entire populations—experience it took overseas. Roosevelt compared Filipinos to the Apache and the Sioux, all of whom he regarded as savages. He argued if Anglo-Americans were “morally bound to abandon the Philippines, we were also morally bound to abandon Arizona.”102 Both ideas were, to him, ridiculous.

As one historian put it, “territorial expansion was as old as the Union itself.”103 In fact, it’s even older.

American settlement in the West looked very similar to British colonization in the North Atlantic. In the early 1600s, the British arrived in the region, established permanent settlements, and displaced the native population.104 It’s a form of colonization called settler colonialism. It’s pretty similar to American expansion across the continent. They arrived in the region, established permanent settlements, and through war, forced migration, and disease, they displaced the native population.105

Sounds similar, right? Some Americans made the connection explicit. In 1885, John Fiske reflected, “The work which the English race began when it colonized North America is destined to go on.”106

Maybe America was an empire all along….

CONCLUSION [55:52-57:38]

American imperialism was, therefore, both new and old.

The Nation’s interventionalist policy makes no sense removed from its historical context. It was deeply rooted in the economic, social, and intellectual trends of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As the US seized Hawaii, Guam, Puerto Rico and the Philippines and flexed its power in Cuba and Panama, Americans debated among themselves and expressed conflicting ideas about religion, economics, gender, race, civilization, and national destiny.

But long before that, the country had begun acquiring new territories and subjugating native populations. It’s a story as old as the Nation itself. The old imperialist impulse simply found a new expression.

Thanks for listening.

[American History Remix is written and produced by Will Schneider and Lyndsay Smith. For the latest updates, be sure to follow us on Instagram and Threads. Check out our website for episode transcripts, recommended reading, and resources for teachers. That’s AmericanHistoryRemix.com.]

REFERENCES

Adas, Michael. "From Settler Colony to Global Hegemon: Integrating the Exceptionalist Narrative of the American Experience into World History." The American Historical Review 106, no. 5 (2001): 1692-1720.

Dobson, John M. America's Ascent: The United States Becomes a Great Power, 1880–1914. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1978.

Foner, Eric, ed. Voices of Freedom: A Documentary History. Vol. 2. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2011.

Hahn, Steven. A Nation Without Borders: The United States and Its World in an Age of Civil Wars, 1830-1910. New York: Penguin Random House, 2016.

Herring, George C. From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Hoganson, Kristin, L. American Empire at the Turn of the Twentieth Century: A Brief History with Documents. Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2016.

Hoganson, Kristin L. Fighting for American Manhood: How Gender Politics Provoked the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000.

Jacobs, Margaret D. “Getting Out of a Rut: Decolonizing Western Women’s History.” Pacific Historical Review 79, no. 4 (Nov. 2010): 585-604.

Jacobson, Matthew Frye. Barbarian Virtues: The United States Encounters Foreign Peoples at Home and Abroad, 1876-1917. New York: Hill and Wang, 2001.

Kashay, Jennifer Fish. “Agents of Imperialism: Missionaries and Merchants in Early-Nineteenth-Century Hawaii.” The New England Quarterly 80, no. 2 (Jun., 2007): 280-98.

Mangeloja, Esa. "Martin Luther’s Business Ethics and the Economic Utopia." Journal of Economics, Theology and Religion 3, no. 1/2 (2023): 1-22.

Merriman, John. A History of Modern Europe: From the Renaissance to the Present. 3rd ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2009.

Newbigin, Lesslie. Foolishness to the Greeks: The Gospel and Western Culture. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1988.

Williams, Walter L. “United States Indian Policy and the Debate over Philippine Annexation: Implications for the Origins of American Imperialism.” The Journal of American History 66, no. 4 (Mar., 1980): 810–31.

NOTES

1 Kristin L. Hoganson, Fighting for American Manhood: How Gender Politics Provoked the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 39.

2 Steven Hahn, A Nation Without Borders: The United States and Its World in an Age of Civil Wars, 1830-1910 (New York: Penguin Random House, 2016), 493-94.

3 “Washington’s Farewell Address, 1796,” Mount Vernon, accessed May 9, 2024, https://www.mountvernon.org/education/primary-source-collections/primary-source-collections/article/washington-s-farewell-address-1796/.

4 “Monroe Doctrine (1823),” National Archives, accessed May 9, 2024, https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/monroe-doctrine.

5 Kristin L. Hoganson, American Empire at the Turn of the Twentieth Century: A Brief History with Documents (Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2016), 3. George C. Herring, From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 301-2. John Merriman, A History of Modern Europe: From the Renaissance to the Present, 3rd ed. (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2009), 839-40.

6 Hahn, A Nation Without Borders, 396.

7 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 208-9. Jennifer Fish Kashay, “Agents of Imperialism: Missionaries and Merchants in Early-Nineteenth-Century Hawaii,” The New England Quarterly 80, no. 2 (Jun., 2007): 281-82.

8 Kashay, “Agents of Imperialism,” 284-88.

9 Kashay, “Agents of Imperialism,” 294.

10 Kashay, “Agents of Imperialism,” 295-96.

11 Hahn, A Nation Without Borders, 396-97.

12 Hahn, A Nation Without Borders, 396-97.

13 Hoganson, American Empire at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, 10. Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 262.

14 John M. Dobson, America's Ascent: The United States Becomes a Great Power, 1880–1914 (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1978), 54.

15 Hahn, A Nation Without Borders, 396-97.

16 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 206.

17 Dobson, America’s Ascent, 63. Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 296.

18 Dobson, America’s Ascent, 60, 62.

19 Dobson, America’s Ascent, 63.

20 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 297.

21 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 305-06.

22 Jacobson, Barbarian Virtues, 54.

23 Jacobson, Barbarian Virtues, 52, 54.

24 Jacobson, Barbarian Virtues, 51.

25 Lesslie Newbigin, Foolishness to the Greeks: The Gospel and Western Culture (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1988), 109.

26 Ex 20:17.

27 Col. 3:5.

28 Matt. 19:21-26.

29 Newbigin, Foolishness to the Greeks, 106-08.

30 Esa Mangeloja, "Martin Luther’s Business Ethics and the Economic Utopia," Journal of Economics, Theology and Religion 3, no. 1/2 (2023): 7, 12.

31 Newbegin, Foolishness to the Greeks, 109.

32 Hoganson, American Empire at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, 10.

33 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 309-310.

34 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 310. Hoganson, American Empire at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, 11.

35 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 310.

36 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 312. Hoganson, American Empire at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, 11.

37 Hoganson, American Empire at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, 11.

38 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 311.

39 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 299-300.

40 Jacobson, Barbarian Virtues, 3.

41 Hoganson, Fighting for American Manhood, 37.

42 Hoganson, Fighting for American Manhood, 30, 32.

43 Hoganson, Fighting for American Manhood, 12.

44 Hoganson, Fighting for American Manhood, 34.

45 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 302.

46 Hoganson, Fighting for American Manhood, 12, 16, 36.

47 Hoganson, American Empire at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, 11.

48 Quote from Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 313. Hoganson, Fighting for American Manhood, 68.

49 Hoganson, Fighting for American Manhood, 68.

50 Quote from Representative James A. Norton (D-Ohio). Hoganson, Fighting for American Manhood, 69.

51 Hoganson, American Empire at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, 11-12.

52 Hoganson, American Empire at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, 11-12.

53 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 309, 316. Hoganson, American Empire at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, 13.

54 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 314-16.

55 Hahn, A Nation Without Borders, 493-94. Hoganson, American Empire at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, 13.

56 Hoganson, Fighting for American Manhood, 39.

57 Hoganson, American Empire at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, 72.

58 Hoganson, American Empire at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, 17.

59 Hahn, A Nation Without Borders, 494.

60 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 316.

61 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 317-18.

62 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 319.

63 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 318-19.

64 Hoganson, Fighting for American Manhood, 133.

65 Hoganson, American Empire at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, 12.

66 Hoganson, American Empire at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, 14.

67 Hoganson, American Empire at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, 13-14, 71.

68 Hoganson, Fighting for American Manhood, 133.

69 Hoganson, Fighting for American Manhood, 134-35.

70 Hoganson, Fighting for American Manhood, 134, 137.

71 “President McKinley on American Empire (1899),” in Voices of Freedom: A Documentary History, ed. Eric Foner (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2011), 2:68.

72 Jacobson, Barbarian Virtues, 140.

73 Jacobson, Barbarian Virtues, 146-47.

74 Jacobson, Barbarian Virtues, 140.

75 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 321.

76 Hoganson, American Empire at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, 20-21. Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 321, 327.

77 Hoganson, American Empire at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, 21.

78 Hoganson, American Empire at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, 20.

79 Hoganson, American Empire at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, 21.

80 Edward J. Davis, “They Held Him Under the Faucet (1902)” in American Empire at the Turn of the Twentieth Century: A Brief History with Documents, Kristin L. Hoganson (Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2016), 84-86.

81 Hoganson, American Empire at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, 21; Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 327.

82 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 329.

83 Hoganson, American Empire at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, 21.

84 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 323.

85 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 323.

86 Jacobson, Barbarian Virtues, 152.

87 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 323.

88 Jacobson, Barbarian Virtues, 160.

89 Jacobson, Barbarian Virtues, 161.

90 Hoganson, American Empire at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, 25.

91 Hoganson, American Empire at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, 2, 25.

92 Delegate to House of Representatives from Guam and Virgin Islands, U.S. Code 48 (1972), § 1711. https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?path=/prelim@title48/chapter16&edition=prelim.

93 “American Samoa,” U.S. Department of the Interior, accessed May 9, 2024, https://www.doi.gov/oia/islands/american-samoa.

94 Hahn, A Nation Without Borders, 498-99.

95 Hahn, A Nation Without Borders, 499. Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 367-68.

96 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 367. Hoganson, American Empire at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, 24.

97 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 368.

98 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 367-68.

99 Hahn, A Nation Without Borders, 499. Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 369.

100 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 301.

101 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 317.

102 Walter L. Williams, “United States Indian Policy and the Debate over Philippine Annexation: Implications for the Origins of American Imperialism,” The Journal of American History 66, no. 4 (Mar., 1980), 825.

103 Dobson, America’s Ascent, 13-14.

104 Michael Adas, "From Settler Colony to Global Hegemon: Integrating the Exceptionalist Narrative of the American Experience into World History," The American Historical Review 106, no. 5 (2001): 1704-1707.

105 Margaret D. Jacobs, “Getting Out of a Rut: Decolonizing Western Women’s History,” Pacific Historical Review 79, no. 4 (Nov. 2010): 599-601.

106 Williams, “United States Indian Policy and the Debate over Philippine Annexation,” 817.