VOL. 3 EPISODE 5: AMERICAN BEER

Who doesn’t like beer? Lots of people, apparently. As Americans sought to remedy the ills plaguing their society, beer was caught in the cross hairs. We tell the story of how the American beer industry rose to defend itself against Progressive Era reforms in a decades-long fight. And it almost worked.

“To Alcohol—the cause of, and solution to, all of life’s problems.”

- Homer Simpson

INTRODUCTION [0:00-04:01]

In Chicago, in 1871, a cow in the barn of Catherine and Patrick O’Leary supposedly kicked over a lantern. The cow probably wasn’t malicious, but the bastard animal burnt down Chicago.

The flames from the lantern leapt out of the barn and spread across the neighborhood. The winds carried it north to the industrial district where it found stores of lumber and coal. Then, flames engulfed the city gasworks and exploded. The raging fire burned so hot that fire fighters could only flee. In downtown, the brick buildings collapsed under the heat. The fire raged for 20 hours before it finally burned itself out.

In the end, the “Great Chicago Fire” destroyed over 3 square miles of the city and 18,000 buildings, killed 300 people, and left 75,000 homeless.1

You know what else it did? It destroyed nineteen breweries. The people of Chicago were left with nearly no access to beer. The story goes that to fill the void, brewers like Schlitz and Pabst from Milwaukee, Wisconsin, some 90 miles north, shipped beer to the city. Pabst sent beer on steam ships down Lake Michigan. Schlitz sent barrels on a barge and even gave free beer to survivors of the fire.2 And that’s the story of how beer saved Chicago.

Beer was a favorite beverage of Americans. It was also one of the most controversial. A generation after Chicago’s Great Fire, Americans voted to amend the Constitution and prohibit the manufacture and sale of alcohol. How did this happen? How did beer go from being part of disaster recovery to an outlawed drink?

In the early twentieth century, various groups of Americans sought, in their own ways, to reform society. We refer to this time as the Progressive Era. Some wanted economic reforms, others fought to give women the right to vote. Some wanted to address public health, or immigration, taxation, environmental issues, workplace safety, etc. These were diverse but overlapping interest groups who believed their efforts would improve, or progress, the world, hence the “Progressive Era.”

Today, we’re going to make sense of the numerous, bewildering, and interrelated movements by taking one case study—beer.

Many Americans at the time believed alcohol was a social evil and waged a cultural and political war against it. But while reformers campaigned against alcohol, the beer industry sought to distinguish itself as a healthy alternative to hard liquor. It lost the fight, but it was a close call.

By exploring the fight over alcohol, especially beer, we see the overlapping interests and complex factors that shaped the Progressive Era.

Let’s dig in.

—Intro Music—

[Welcome to American History Remix, the podcast about the overlooked and underexplored parts of American history. We’re glad you’re here!]

BEER IN EARLY AMERICA [04:01-08:06]

The Progressive Era was roughly the first two decades of the 20th century, but the roots of progressive reform go back decades. Let’s back up.

Americans began brewing beer in the 1600s when colonists got tired of waiting for imported ale from Europe. Those in the English colonies brewed English-style ales, stouts, and eventually porters. Beer was a healthy alternative to the often-questionable drinking water.3

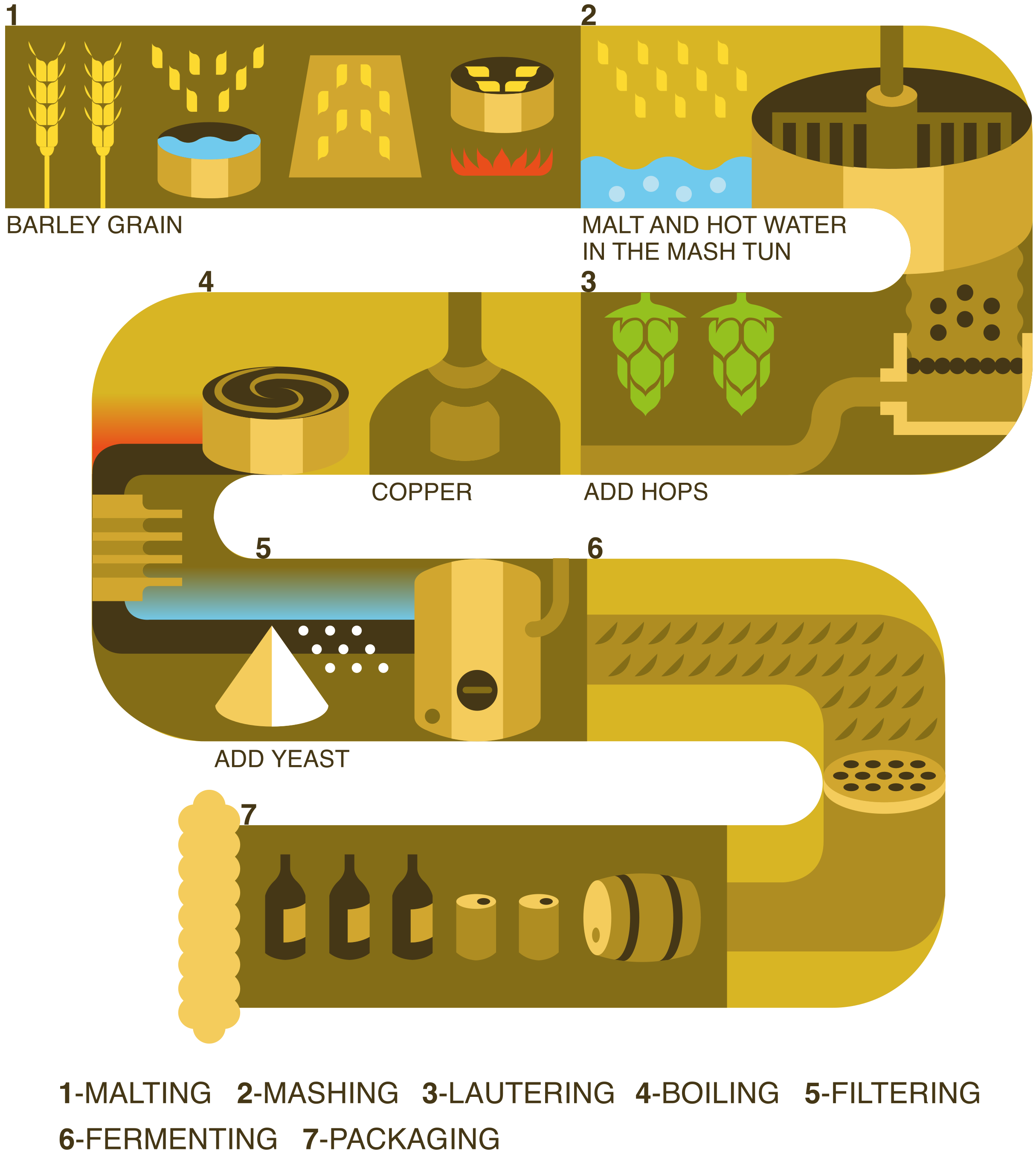

The specifics vary depending on the kind of beer, but there are some basic steps in the brewing process. Essentially, a cereal grain needs to be dampened, then heated, and then dried to create malt. The malt is then ground and either infused or decocted with water and then strained and cooled. Then, brewers add yeast and let it ferment.4

Brewing process. Image created during "DensityDesign Integrated Course Final Synthesis Studio" at Politecnico di Milano, organized by DensityDesign Research Lab in 2016. Credits goes to Piero Barbieri. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, via Wikimedia Commons.

In the colonial era, beer was commonly brewed at home or in small batches by local breweries. Colonists lacked the infrastructure and resources to support large-scale brewing. Other forms of alcohol were, therefore, more popular. Hard apple cider was easier to produce locally, colonists got rum from the Caribbean, and the wealthy preferred imported wine.

In short, drinking alcohol was common and uncontroversial, and beer was just one option among many.5

Things began to change in the 19th century. The first decades of the 1800s were arguably the drunkest decades in American history. In 1830, the average American consumed over five gallons of distilled alcohol alone.6

And beer became more popular. You know who people blamed? The Germans. They immigrated to the US in large numbers in the Antebellum period. And Germans love beer. I know because I’m German.

Germany wasn’t yet a united country, but the German-speaking people of Northern Europe drank beer a lot. They drank to celebrate, they drank to solidify a political alliance, they drank before going to battle and killing their enemies. Many viewed beer as “liquid bread.” It was made from grain after all, and it was an important source of calories. When Germans came to America, they brought with them their knowledge of, and desire for, beer. They established their own breweries, bars, and beer gardens with alcohol and entertainment for the whole family.7

“Lager Bier,” Mensing & Stecher, lithographers, circa 1879. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

German-style lagers became especially popular. And it preserved their German heritage in a new land. One popular toast went:

“Twas drank in the ‘fader land’ first,

But now we drink it here,

Then drink it boys! Drink Freely!Three rounds for lager Beir!”8

It’s catchy, right?

That said, access to beer was still limited because transportation networks were primitive. If someone wanted to drink a beer from a specific brewery in their home, then they had to purchase by the barrel. Or they would send someone to a local saloon with a growler or a bucket. Often, this chore fell to children. Parents would send their kids to fetch buckets of beer.9 We used to be a proper country.

EARLY REFORM MOVEMENTS [08:06-11:54]

In this context, numerous voices began to call for temperance. They encouraged individuals to willingly abstain from alcohol or to at least drink less. From those voices came nationwide organizations like the American Temperance Society, founded in 1826.10

Temperance groups relied heavily on moral and religious arguments. Abstaining from alcohol is not a teaching of the historic church. Christian support for temperance was a new and distinctly American development. Nevertheless, preachers and temperance leaders increasingly equated drinking any alcohol with sinning. A willingness to resist alcohol was like resisting evil itself.11

“Come father, won’t you come home?” From Ten Nights in a Bar Room, 1854 printing. Immensely popular novel that was adapted into a play and several films in the 1910s-30s. Timothy Shay Arthur, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Lyman Beecher was a minister and one of the founders of the American Temperance Society. He preached, “Intemperance is the sin of the land and is coming in upon us like a flood.” Thus, more and more temperance leaders petitioned their listeners to sign a pledge to totally abstain from alcohol.12

Temperance was far from the only such movement at the time. A variety of reform movements organized and spread in the antebellum era. The American Anti-Slavery Society was founded in 1833. Other organizations promoted, education, sanitation, women’s rights, and prison reform.13 These were the predecessors to the reform movements of the Progressive Era.

These sorts of reforms were popular among middle-class, evangelicals, especially women. Americans in the 19th century conceived of the world as being divided by gender. So conceived, there were two spheres of life. A man’s place was outside the home. Work, politics, and public life were his sphere of influence. A woman’s sphere was the home, where she cared for her family. But voluntary religious organizations offered women a space to engage with public affairs. A space they could not find anywhere else.14

So, many women joined the temperance movement, or they joined other organizations championing Sunday school, orphanages, prison reform, etc.15 In many cases, the reform movements bled into one another. In fact, the origins of the women’s rights movement itself are in the abolitionist movement.

Angelina Grimke, a champion of women’s rights, came to that movement through abolitionism. In 1837, she wrote, “Since I engaged in the investigation of the rights of the slave, I have necessarily been led to a better understanding of my own; for I have found the Anti-Slavery cause to be the high school of morals in our land.”16

The temperance movement also aided the women’s rights movement. It gave women a public voice. Numerous women reformers embraced the moral and religious arguments against alcohol and participated in temperance societies and temperance education.17

BEER RESPONDS TO TEMPERANCE [11:54-12:46]

How did the beer industry reply? By claiming that beer was a temperance beverage. The industry’s whole argument rested on the fact that it was different from hard alcohol.

Beer has a much lower alcohol percentage, and, unlike liquor, beer provided the benefits of food, it was medicinal, and it could be consumed in moderation. They claimed this distinguished it from whiskey, rum, and gin. Those drinks were the real problem, not good old beer, so the argument went.18

Essentially, the beer industry tried to walk a middle ground between a heavily drinking society and the growing resistance to alcohol.

MODERATE SUCCESS [12:46-14:03]

Despite the novelty of the temperance movement, it enjoyed surprising success. By the late 1840s, the average yearly consumption of alcohol decreased from over five gallons a person to less than two.19

Furthermore, in the 1850s, temperance groups became more directly political. While religious and moral arguments did the trick in some communities, many temperance leaders sought more direct, legal intervention. They managed to enact prohibition in 13 states across the Northeast and the Midwest. It’s remarkable actually. However, nearly all of those states quickly overturned prohibition in the 1860s. By 1875, only Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont maintained prohibition.20

Killing beer wasn’t so easy after all, and the fight only got more challenging as the century wore on.

GROWTH OF BEER INDUSTRY [14:03-16:37]

Following the Civil War, the country grew geographically as Americans settled the far West, and it grew economically due to the Industrial Revolution. Both developments affected beer.

German brewers spread west to cities like Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Louis, Denver, San Francisco, Portland, and Olympia. Agriculture in the West also helped beer production. Hops, a key ingredient in lager, grew well on the West Coast.21 By the 1880s, German lager was the most popular style of beer in America.22

The Industrial Revolution brought changes to the brewing process, storage and distribution of beer. It allowed breweries to produce more beer and to ship it farther than ever before.

Successful companies turned their small breweries into multi-story, highly mechanized factories. Artificial refrigeration helped preserve hops during transportation, providing brewers with a better-quality ingredient.23

Pabst Brewing Company's Milwaukee Beer, New England Depot, 1898. See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

In the 1880s, pasteurization and improvements in bottle design made bottling beer an easy and stable method for shipping it across the country. Add this to the growing railroad network and refrigerated freight cars and beer transportation took off. Bottled beer was now sold in stores, hotels, and restaurants. Mail-order beer even became common.24

But don’t worry. Children still fetched buckets of beer for their parents and even made deliveries to factory workers on their lunch breaks.

Beer became so popular among Americans that it surpassed other alcoholic drinks by the mid-1880s. Between 1880 and 1895, beer production in the country more than doubled. The industry’s total capital increased from $91 million to $232 million. Companies like Pabst and Anheuser-Busch became national brands. By 1880, American beer production ranked third worldwide, behind only Germany and the UK.25

SECOND WAVE OF TEMPERANCE [16:37-17:46]

As industrialization fueled the beer industry, it also led to another wave of reform movements.

The new wave of temperance advocates retained the earlier generation’s moral and religious arguments and worked to educate the public on the “liquor problem” in the country. But the temperance movement was evolving into the prohibition movement.26

The most powerful organizations in the revitalized movement were the National Prohibition Party, founded in 1869, and the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, founded in 1874. Both organizations put on plays and published textbooks to educate children about the dangers of alcohol. They founded prohibition newspapers in the 1880s and 90s, and together their publications reached over 100,000 subscribers.27

And both groups somehow still exist today.

WOMEN, ALCOHOL, & WOMEN’S RIGHTS [17:46-21:30]

Women gained more public influence through the reform movements, including prohibition, even as their methods became more political.

But…recall America’s prevailing idea that men should engage in the public sphere while a woman’s place was at home. How then did so many women come to join and even lead the progressive movements?

You see, women were allowed a greater voice in public affairs when issues affecting the home became societal issues. For example, women led the way in public sanitation reform, because cleanliness and sanitation were their responsibilities at home. It was therefore “an extension of their domestic affairs.” Likewise, by the late 1800s, many counties allowed women to vote on issues which directly affected children, like voting for local school boards since education was within their realm of responsibility.28

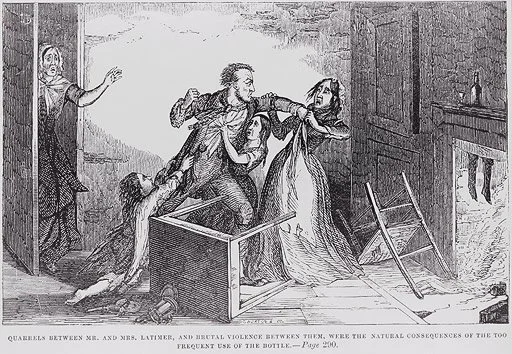

Other reforms centered on protecting the home itself. For many women, the desire to eliminate alcohol stemmed from the desire to protect the home from sexual and domestic violence exacerbated by alcoholism. Mother Stewart was a founding member of the Ohio Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. She often spoke publicly about alcoholism and domestic violence.29

Temperance illustration of drunkard hitting his wife, 1871. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, via Wikimedia Commons.

In her memoir, published in 1890, she shared story after story of abused women living in poverty due to their husbands’ drunkenness. For example, she shared the story of a woman with two young kids who kept the abuse she suffered from her husband a secret, even when he threatened to kill her. Finally, after eight long years, she took her children, fled, and found protection with her parents. The woman concluded “if women could only vote, how soon would the liquor dens be closed and all this suffering ended.”30

For many women, the fight against alcohol was personal, and it bled into the fight for women’s rights.

At the same time that women reformers worked to educate the public on the dangers of alcohol and supported legislation to limit the alcohol industries, there emerged another progressive movement—the suffrage movement, which sought to give women the right to vote nationally.

Abigail Scott Duniway signing first Equal Suffrage Proclamation ever made by a woman, 1912. Pictured with Oregon Governor Oswald West and acting president of the Equal Suffrage Association Dr. Viola M. Coe. Library of Congress, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

These movements, however, did not represent all women equally. They were primarily made up of upper or middle class, white, Protestant women. And some women’s rights advocates did not support prohibition outright. Abigail Scott Duniway argued that suffrage was more important than temperance. Temperance, while perhaps significant, was ultimately a distraction. Instead, she argued, women should fight for the right to vote and then, with their political rights secured, they could choose prohibition or not.31

BEER AS MEDICINE [21:30-24:04]

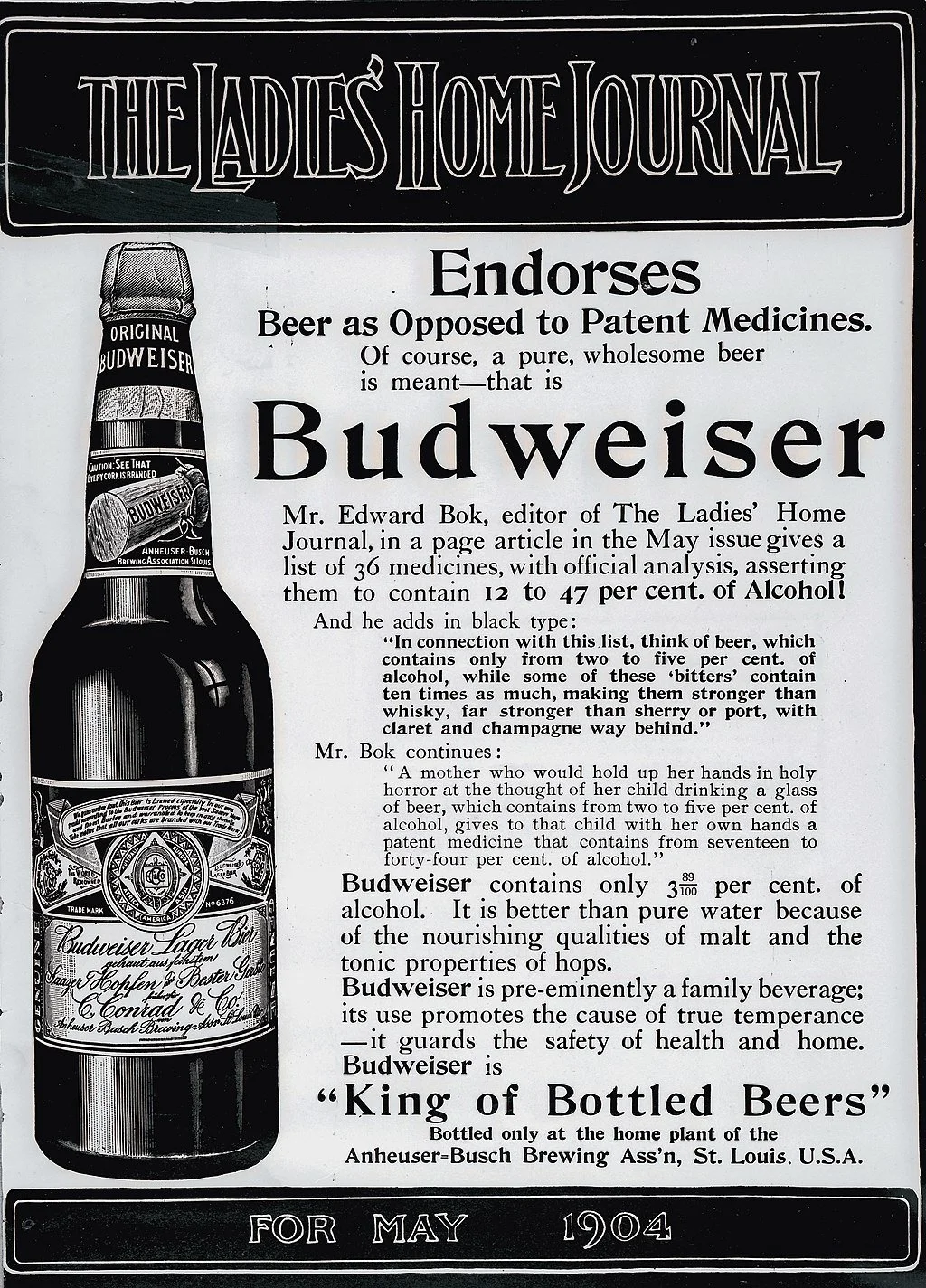

Without denying the arguments against alcohol, beer supporters continued to argue that beer was a healthy, wholesome drink, distinct from liquor. To bolster their position, they turned to the scientific community.

Beer advocates embraced the arguments of Benjamin Rush, one of the country’s Founding Fathers and a physician. He had warned of the dangers of hard liquor, but beer was nourishing…and tasted good.32 Advocates also noted how physicians still commonly prescribed alcohol to treat a number of ailments. Authors of a medical handbook published in 1879 warned against the consumption of hard alcohol but suggested that some alcohol could refresh the nervous system after intense physical or mental labor. It could increase a patient’s appetite and help indigestion. Hops, the book claimed, was a sedative that helped with sleep and could even treat rickets.33

…I don’t know if any of that’s true. But the arguments held weight based on the understanding of the day.

The United States Brewers’ Association, founded in 1862, was by far the most effective organization in the fight against prohibition. In 1880, they published a book featuring statements from physicians, chemists, and health officials that supported beer as a harmless, mildly alcoholic and nutritious drink. They recommended that beer be used instead of liquor in medical treatments.34

This resulted in a public debate over the healthiness of beer.

Advertisement for Budweiser beer featured in The Ladies Home Journal, 1904. See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Eventually, the American Medical Association joined in. They published a journal in 1893 which debunked much of the literature on the uses of alcohol and called for further study of the issue. That same year, the American Medical Temperance Association published its first journal issue, which included multiple articles again discrediting the uses of alcohol.35

In essence, the medical community was divided on the medicinal value of alcohol, and the debate continued into the 20th century.

BEER & THE ECONOMY [24:04-24:45]

Furthermore, the beer industry heavily contributed to local and federal government through taxes and license fees.

Between 1873 and 1916, beer, wine, and liquor together generated between 20 and 40 percent of the nation’s total tax revenue. One statistic showed that brewers alone paid an estimated $1.2 billion to the United States Treasury between 1863 and 1909.36

The federal government was in no rush to prohibit such a valuable industry.

FAILURES OF SECOND WAVE OF TEMPERANCE [24:45-26:26]

Even so, prohibitionists pushed for a national law eliminating alcohol. In 1876, Republican Representative Henry W. Blair of New Hampshire presented the first prohibition bill to amend the U.S. Constitution. The bill targeted distilled liquor only, beer was left out. It never made it to the floor of Congress. In 1880, Republican Senator Preston Plumb of Kansas introduced a stronger amendment barring both beer and liquor. It also failed to reach the floor of Congress.37

In 1887, Blair tried again. With support from both the Prohibition Party and the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, he proposed another constitutional amendment to prohibit alcohol in the country. This one made it to a vote…but it failed. The next prohibition amendment brought before Congress would not surface until 1914.38

Despite its early failures, the switch from temperance to legal prohibition represented a broader cultural shift. Rather than relying on the willful action of individuals, Americans started to believe that the government should have a greater role in promoting public welfare. Many progressive reforms would require strengthening local and federal government.39

SALOONS [26:26-30:22]

In the late 1800s, the anti-alcohol movement was disorganized and disillusioned. Moral arguments hadn’t ended alcohol consumption and legal prohibition had failed. They needed a new direction.40 The Anti-Saloon League answered the call. Temperance advocates created the organization in Ohio in 1893. As their name suggests, they targeted saloons rather than focusing on radical prohibition laws.41 Saloons were incredibly popular and, in fact, had boomed during the Industrial Revolution. Between 1870 and 1900, the number of saloons in the United States tripled from 100,000 to 300,000.42

Temperance advocates viewed saloons as the embodiment of all kinds of evil. Not only did they serve alcohol, but many also housed other illicit activities like gambling and prostitution.43

Class and ethnic tensions colored the hostility towards saloons. They played a significant role in the everyday life of immigrants and the working-class, offering a place for relaxation and entertainment after work. Saloons were widely known as “workingman’s clubs,” or less glamorously as “poor man’s clubs.” Some saloons offered bowling, billiards, singing, and dancing. Others rented space to social clubs, making them important centers in their communities.44

Bartenders and patrons holding beer glasses at Hotel Globe bar, Seattle, circa 1910. University of Washington, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

In the late 1800s, saloons began offering a free lunch with the purchase of a drink. Workers could pay 5 cents for a beer and then get a whole meal. You can imagine the appeal. I was once at a bar, and the waitress put a plate of brownies in front of me. I clarified that I hadn’t ordered brownies, and she said “It’s Monday. Monday is brownie day. Eat up.” Best bar I’ve ever been to. It was Kroll’s West in Green Bay, Wisconsin, if you’re curious—across the street from Lambeau Field.

Anyway, workingmen had better luck finding a good meal in a saloon than anywhere else. Saloonkeepers cut deals with suppliers and acquired higher quality food at much lower prices than the average worker could, often making the free lunches better than the meals cooked at home.45

Anti-Saloon advocates argued that, despite their importance to the working class, saloons were ultimately harmful. At one anti-saloon gathering in 1894, Reverend John A. Watterson argued that saloons looked alluring, especially to young men working in the city, but they were in fact traps which corrupted the men and turned them into poor, miserable drunkards.46

“The Home vs. The Saloon.” Printed by the Detroit chapter of the Anti-Saloon League, circa 1910. See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

They drained government funds. Drunkenness and gambling contributed to poor houses, hospitals, asylums, and orphanages. In fact, alcohol was counterproductive for the working class. Hungover workers are less efficient workers; drunk workers are even worse.47

The attack on saloons was an indirect attack on the brewers themselves, because breweries often owned or invested in local saloons.48

And so, temperance advocates made saloons their primary target. Private drinking became a secondary issue.

LOCAL OPTION [30:22-32:29]

Temperance advocates looked to limit the institution through local option laws. These laws did not address consumption but outlawed the sale of alcohol. And they were geographically limited to a city, county, or perhaps a neighborhood. The goal was to confront the saloons by eliminating their most desired product.49

Local option laws achieved much on paper but affected little in practice. Several counties within a state could prohibit the sale of alcohol, but if they were sparsely populated, then few people were practically affected. Sometimes, cities voted separately from the county they were in. If one city still allowed alcohol, then nearby saloons could just relocate there and continue to operate in an otherwise dry county.50

And the beer industry responded to anti-saloon sentiment by promoting other ways to consume alcohol. Beer was already sold in grocery stores, restaurants, and hotels, but breweries increased their home-deliveries and promoted family-friendly beer gardens.51

Unfortunately, buckets of beer declined and have never recovered.

"Picnickers enjoying food and drink, including Weinhard beer," 1910. Gerald W. Williams Collection, Oregon State University, via Oregon Digital.

Industry advocates also took an offensive stance, arguing that prohibition was impossible. Robert Crain of the United States Brewers’ Association claimed that prohibition would not work because it was based upon “the insane delusion that the body politic can be prevented from drinking.” Instead of having licensed, tax-paying establishments serving alcohol, he argued that prohibition would foster illegal establishments—speakeasies—which already existed in dry areas.52

PURE FOOD MOVEMENT [32:29-36:20]

In the midst of this struggle, the anti-saloon movement found an ally in another reform group—this one fighting for pure food.

Food production at the time was unregulated and took place largely out of sight of consumers, which allowed companies to adulterate their products with secret, harmful ingredients. For example, “Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup” was advertised as medicine to help children sleep. But, in 1888, it was revealed that the brand’s medicine was an opioid.53 As a parent, I’d be pissed off too.

So, the Pure Food Movement fought for decades to ensure the health and quality of food, drink, and medicine. They finally achieved success when Upton Sinclair published his novel The Jungle in 1906. The book dramatized the plight of an immigrant family living in the meat-packing district of Chicago. Sinclair was a prohibitionist. His intent was to show the working conditions of the poor and how saloonkeepers manipulated patrons and kept them in poverty.54

Ironically, the American audience was drawn more to the depictions of the unsanitary conditions in the meat industry—how rotten meat was sold to the public. The success of the novel inspired real action. Within a year of its publication, Congress passed the first Pure Food and Drug Act, creating what we now call the Food and Drug Administration.55

Temperance advocates, meanwhile, were eager to expose any adulterants found in alcohol. Such evidence would only support their long-held argument that alcohol was poison.56

But nutrition science was in its infancy, and some leaders took a very broad definition of an “adulterant.” The term included supposedly harmful ingredients like pepper, sugar, and mustard.57 In 1879, one report claimed that adulterated beer commonly contained coriander seeds, cayenne pepper, and salt.58

It was probably a weird-tasting beer, but viewing cayenne pepper or mustard as an adulterant is an…odd position. But it gets even stranger, because the arguments made by Pure Food and Temperance advocates were colored by anti-immigrant prejudice.

Old stock Americans blamed immigrants for crime, political radicalism, and social unrest.59

Food has strong cultural ties, and those who disliked certain immigrant cultures also tended to dislike their diets. But some Pure Food advocates went further. They argued that foreign diets lead to immorality. They claimed immigrants overate and their food was too complex with too much seasoning. That caused indigestion, the remedy for which was alcohol. Put simply, poor diets lead to poor health, which lead to poor morals, which lead to vice and social decay.

Good Americans, they argued, don’t overeat and prefer plain food without alcohol…right.60

The Pure Food movement was born out of a real problem. But if you’re confused, don’t worry—because they embraced some weird arguments.

BEER & PURE FOOD [36:20-37:48]

The beer industry was thus scrutinized by both temperance and pure food advocates. How did they respond? By claiming that beer was a pure drink.

Beer advocates generally supported pure food regulation. In fact, many brewers honored the conditions set by a Purity Law passed in Bavaria in 1516, which limited brewers to certain pure ingredients.61

Advertisement for Malt Rainier, a malt tonic produced by the Seattle Brewing & Malting Company, makers of Rainier Beer, 1909. See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

If advocates could show that beer was in fact a “pure food,” they could win big. So, brewers appeared before Congress in 1902 and voiced their own concerns about adulterants in food and drink. In 1906, an article published in an issue of the Western Brewer claimed that brewers were “anxious to have a standard of manufacturing set by the government and a government stamp on every keg.”62

Pabst even advertised their beer as an “ideal temperance beverage” and an “ideal family beverage” made with pure and high-quality ingredients. Dozens of other beer brands did the same, promoting their beer as a wholesome beverage.63

TAX REVENUE & REGULATION [37:48-41:18]

Pure Food advocates had so far been unable to convince the public that beer was poison, and the Anti-Saloon League had been unable to undermine saloons at the state and local levels. To eliminate alcohol for the greater good of the Nation, they again needed to change their strategy. In 1913, the Anti-Saloon League pledged their support to a new constitutional amendment making the manufacture and sale of all alcohol illegal nationwide.64

One of the major goals of the progressives was economic reform—to address the inequality and instability of the new and unregulated industrial economy. Check out our episode on class violence if you haven’t already.

Economic reformers, like temperance advocates, were forced to constantly change their tactics.

During the Civil War, the federal government instituted the first graduated income tax—a tax where those with more wealth are taxed at a higher rate than those with less. The tax, however, expired soon after the war. In 1894, Congress passed an act again instituting a graduated tax. But the following year, it was struck down by the Supreme Court which ruled that Congress had no authority for such a tax.

To address the growing gap between the wealthy and the poor, Congress had two options: pass another law and hope the court would overturn its prior ruling or add an amendment to the Constitution. They went for the second option. The House and Senate passed the 16th Amendment in 1909. The states ratified it in 1913, granting Congress the power to institute a graduated income tax.65

But what does tax reform have to do with beer?

Well, it transformed the federal budget. Income tax created a stream of revenue that made the federal government less reliant on the liquor tax, weakening the beer industry’s relationship with the federal government. It was exactly what the anti-liquor advocates needed in their journey to secure national prohibition.66

Meanwhile, reformers also sought to close the loopholes in the local option laws. In 1913, Congress passed the Webb-Kenyon Act which limited the transportation of alcohol between states. The Reed-Randall Act of 1917 made it illegal to transport beer in the mail to dry areas, limiting the transportation of alcohol even within a state. By addressing the issue at the federal and state levels, local laws prohibiting alcohol now had some teeth, and the Prohibition movement was gaining steam.67

The beer industry was now on the defense.

BEER ON THE DEFENSE [41:18-42:42]

To combat the rising tide of prohibition, the beer industry offered several arguments. Anti-beer advocates often argued that alcohol caused poverty. Rather than deny the relationship between alcoholism and poverty, the beer industry attempted to reverse the narrative and show how beer, unlike liquor, was a solution to social problems. Alcoholism, they argued, was not the only social issue associated with extreme poverty. Sanitation issues, malnourishment, and disease were all factors.68

But sweet, sweet beer, derived from pure ingredients in modern, clean breweries, provided much needed nourishment and vitality that could help combat poverty. Moreover, the beer industry, they pointed out, benefited families by employing thousands of Americans nationwide. So long as it was consumed responsibly, they still argued that beer was “liquid bread.”69

Furthermore, brewers argued that prohibition would deprive them of their personal liberty and their rights as Americans to operate legitimate businesses.70

WORLD WAR ONE [42:42-44:47]

Arguments back and forth between prohibitionists and beer advocates had been going on for years, with varying success and failure on either side. It took a massive event to definitively tip the scales. It was World War One that pushed the Nation over the edge and led to National Prohibition.

The war began in Europe in 1914. The US entered the conflict in 1917, and the Anti-Saloon League capitalized on the situation. They argued that production of alcohol was a waste of resources and manpower. The beer industry used millions of bushels of grain each month and took up valuable space on the railroads. The League argued that those resources should be redirected to the war effort, and enough lawmakers agreed.71

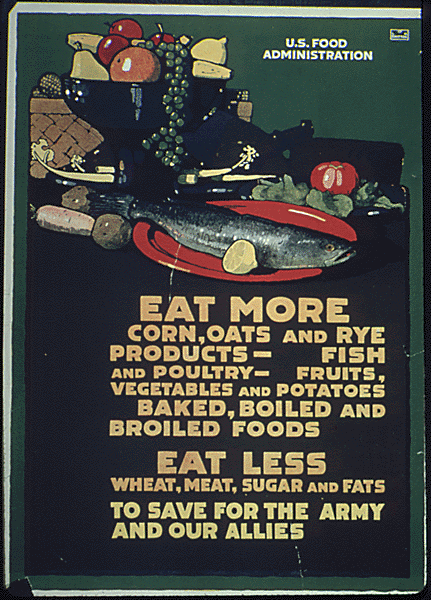

Poster from U.S. Food Administration, circa 1918. National Archives, Records of the U.S. Food Administration, World War I Posters series. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Congress passed the Lever Act in 1917. The act regulated the production and distribution of food, including the production of hard liquor. It almost prohibited beer as well, but enough senators fought to make it exempt. The act was limited and a temporary measure brought on by the war, but it finally achieved some level of national prohibition. It also set a precedent for greater government regulation of food and drink.72

The government began a public campaign with slogans like “food will win the war” and “victory over ourselves” to encourage those on the home front to eat meals without meat or grain.73 Saving those resources for the military displayed self-discipline and was in service to the soldiers on the front lines. Opposing alcohol, in this context, was patriotic.

ANTI-GERMAN SENTIMENT [44:47-46:23]

Furthermore, since the US was at war with Germany, prohibitionists capitalized on anti-German sentiment. The Anti-Saloon League condemned those damn German brewers who, supposedly, aided our enemies and undermined the war effort. Their argument had several layers. First, they claimed that beer made Americans too drunk to work or fight in the war. Second, they claimed that German brewers prevented immigrants from assimilating into American culture. Finally, they claimed German brewers were corrupting politicians through the revenue they provided to the government.74

A WWI recruitment poster showing an anthropomorphized Germany wading through a sea of dead bodies with the slogan, “Only the Navy can Stop This.” Cartoon by William Allen Rogers, 1917. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Anti-German sentiment was strong during the war, and these arguments caught public attention. In 1918, a Senate subcommittee investigated the United States Brewers’ Association. Senator Richard Palmer claimed that fifteen different brewing companies were unpatriotic and secretly funded newspapers which opposed the war. Palmer claimed that breweries were “organizations owned by rich men, almost all of them are of German birth and sympathy.”75

So, not only should Americans abstain from beer for the sake of the war, but the industry itself was, apparently, treasonous.

BEER & WWI [46:23-47:47]

The beer industry, then, had to prove itself loyal to the US. Some brewers changed the names of their products from German to English. Others invested in the war effort. Brewers made private investments in Liberty Bonds, which helped fund the war. Lily Busch was the widow of Adolphus Busch and the daughter of Eberhard Anheuser. She was pretty much brewing royalty and reportedly purchased $100,000 in Liberty Bonds alone. Altogether, her family contributed $500,000 to the American war effort, a clear demonstration of their patriotism.76

Lilly Anheuser Busch and Adolphus Busch. See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The efforts were not enough. Two laws soon restricted beer like distilled alcohol before it. In December 1917, President Woodrow Wilson extended the Lever Act restrictions to both beer and wine. Then, the Agricultural Stimulation Bill, passed in November 1918, prohibited the sale of beer after July 1, 1919. These were still temporary measures, but prohibitionists were already working on a permanent law.77

PROHIBITION & OTHER REFORMS [47:47-49:46]

Congress passed the 18th Amendment of the Constitution in the winter of 1917. When the amendment went to the states, it easily reached the three quarters approval required. By January 1919, 46 of 48 states ratified the amendment—faster than any other amendment to that point in US history. So, in January of 1920, National Prohibition went into effect. It was now illegal to manufacture or sell alcohol—liquor, wine, or beer.78

After decades of effort, the prohibition movement had succeeded. It was the victory they had been fighting for. And, it came with other progressive victories too.

The 18th Amendment was just one of four constitutional amendments added during the Progressive Era. As we saw, the 16th Amendment, ratified in 1913, allowed Congress to implement a graduated income tax. That same year, the 17th Amendment allowed voters to directly elect Senators. Previously, they were appointed by state legislatures. Coming on the heels of Prohibition, the 19th Amendment, ratified in 1920, granted women the constitutional right to vote.79

Then, in 1921, Congress passed the Johnson Act, the first in a series of legislation which limited immigration to the US by establishing a race-based quota system for entry.80 Consider these alongside the economic and public health reforms we covered earlier. The Progressive Era transformed American society and government.

CONCLUSION [49:46-51:58]

As the story of American beer shows, progressive reforms began long before the Progressive Era—their roots go back nearly a century. The Progressive Era itself was not simple.

The fight for prohibition overlapped with public health concerns, anti-immigrant prejudice, and was indirectly aided by tax reform. The movement was shaped by and simultaneously challenged the dominant gender roles at the time. In short, the progressive reforms were complex.

Further complicating the story is that Prohibition was a failure. Other reforms did succeed. Public health measures led to safer food. I’m glad my wife and daughters can vote. But Americans did not stop drinking. Instead, they drank bootleg alcohol at underground speakeasies and the profits went to organized crime.

So, in 1933, after only thirteen years of Prohibition, the country ratified the 21st Amendment and once again allowed for the manufacture and sale of alcohol. When legal beer came back, Americans embraced it like an old friend.

Cheers, America.

Thanks for listening.

[American History Remix is written and produced by Will Schneider and Lyndsay Smith. For the latest updates, be sure to follow us on Instagram and Threads. Check out our website for episode transcripts, recommended reading, and resources for teachers. That’s AmericanHistoryRemix.com.]

REFERENCES

Andreae, Percy. The Prohibition Movement: In Its Broader Bearings Upon Our Social, Commercial, and Religious Liberties. Chicago: Felix Mendelsohn, 1915.

Barleen, Steven D., “‘Rushing the growler’: can rushing and working-class politicization in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era." Labor History 55, no. 4 (October 2014): 519-537, https://doi.org/10.1080/0023656X.2014.948710 (accessed February 9, 2016).

Baron, Stanley. Brewed in America: A History of Beer and Ale in the United States. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1962.

Bordin, Ruth. Woman and Temperance: The Quest for Power and Liberty, 1873-1900. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1981.

Boydston, Jeanne. Home and Work: Housework, Wages, and the Ideology of Labor in the Early Republic. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Cherrington, Ernest Hurst. The Evolution of Prohibition in the United States of America: A Chronological History of the Liquor Problem and the Temperance Reform in the United States from the Earliest Settlements to the Consummation of National Prohibition. Westerville, OH: The American Issue Press, 1920.

Cochran, Thomas C. The Pabst Brewing Company: The History of an American Business. New York: New York University Press, 1948.

Duis, Perry R. The Saloon: Public Drinking in Chicago and Boston, 1880-1920. 1983; repr., Urbana, IL: Illini Books, 1999.

Duniway, Abigail Scott. Path Breaking: An Autobiographical History of the Equal Suffrage Movement in Pacific Coast States. 2nd ed. Portland, OR: James, Kerns & Abbott Co., 1914.

Dunlop, Pete. Portland Beer: Crafting the Road to Beervana. Charleston, SC: American Palate, 2013.

Foner, Eric, ed. Voices of Freedom: A Documentary History. Vol. 1. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2011.

Fox, Hugh F. “The Prosperity of the Brewing Industry.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 34, no. 3 (Nov., 1909): 47-57.

------ “The Saloon Problem.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 32 (Nov., 1908): 61-68.

Freidberg, Susanne. Fresh: A Perishable History. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009.

Hacker, Louis M. “The Rise and Fall of Prohibition.” Current History 36, no. 6 (Sept. 1, 1932): 662-72.

Hahn, Steven. A Nation Without Borders: The United States and Its World in an Age of Civil Wars, 1830-1910. New York: Penguin Random House, 2016.

Hamm, Richard F. Shaping the Eighteenth Amendment: Temperance Reform, Legal Culture, and the Polity, 1880-1920. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

Howe, David Walker. What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Kerr, K. Austin. Organized for Prohibition: A New History of the Anti- Saloon League. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985.

Kopp, Peter A. Hoptopia: A World of Agriculture and Beer in Oregon’s Willamette Valley. Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2016.

Krout, John Allen. The Origins of Prohibition. New York: Russell & Russell, 1967. First published 1925 by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

Levenstein, Harvey. Revolution at the Table: Transformation of the American Diet. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2003.

McGirr, Lisa. The War on Alcohol: Prohibition and the Rise of the American State. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2016.

Meier, Gary and Gloria Meier. Brewed in the Pacific Northwest: A History of Beer-Making in Oregon and Washington. Seattle: Fjord Press, 1991.

Mittelman, Amy. Brewing Battles: A History of American Beer. New York: Algora Publishing, 2008.

Nugent, Walter. Progressivism: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Odegard, Peter H. Pressure Politics: The Story of the Anti-Saloon League. New York: Columbia University Press, 1928.

Ogle, Maureen. Ambitious Brew: The Story of American Beer. Orlando, FL: Harcourt, Inc., 2007.

One Hundred Years of Brewing: A Complete History of the progress made in the Art, Science and Industry of Brewing in the world, particularly during the last Century. Chicago: H.S. Rich & Co., 1901.

Patterson, Mark and Nancy Hoalst-Pullen, eds. The Geography of Beer: Regions, Environment, and Societies. New York: Springer, 2014.

Powers, Madelon. Faces Along the Bar: Lore and Order in the Workingman’s Saloon,

1870-1920. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1998.

Pratt, J.T. Food Adulteration: or, What We Eat, and What We Should Eat! Chicago: P.W. Barclay & Co., 1880.

Rorabaugh, W.J. The Alcoholic Republic: An American Tradition. New York: Oxford University Press, 1979.

Ross, William G. World War I and the American Constitution. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Rush, Benjamin. An Inquiry into the Effects of Ardent Spirits upon the Human Body and Mind, with An Account of the Means of Preventing and of the Remedies for Curing Them. 6th ed. New York: Cornelius Davis, 1811.

Salem, F.W. Beer, Its History and Its Economic Value as a National Beverage. 1880; repr. New York: Arno Press Inc., 1972.

Skilnik, Bob. A History of Brewing in Chicago. Chicago: Barricade Books, 2006.

Smock, Raymond W., ed. Landmark Documents on the U.S. Congress. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly, Inc., 1999.

Stott, Richard Briggs. Workers in the Metropolis: Class, Ethnicity, and Youth in Antebellum New York City. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1990.

Szymanski, Ann-Marie. Pathways to Prohibition: Radicals, Moderates, and Social Movement Outcomes. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003.

Veit, Helen Zoe. Modern Food, Moral Food: Self-Control, Science, and the Rise of Modern American Eating in the Early Twentieth Century. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2013.

Ward, Jean M. and Elaine A. Maveety, eds. "Yours for Liberty:" Selections from Abigail Scott Duniway’s Suffrage Newspaper. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press, 2000.

White, Richard. The Republic for Which It Stands: The United States During Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, 1865-1896. New York: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Wilson, Bee. Swindled: From Poison Sweets to Counterfeit Coffee – The Dark History of the Food Cheats. London: John Murray, 2008.

Young, James Harvey. Pure Food: Securing the Federal Food and Drugs Act of 1906. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989.

NOTES

1 Richard White, The Republic for Which It Stands: The United States During Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, 1865-1896 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), 488-89.

2 Bob Skilnik, A History of Brewing in Chicago (Chicago: Barricade Books, 2006), 24-25. Iván Román, “How 19th-Century German Immigrants Revolutionized America’s Beer Industry,” HISTORY, A&E Television Networks, March 3, 2022, https://www.history.com/news/beer-history-german-immigrants-american-beer-industry-schlitz-pabst.

3 Ruth Bordin, Woman and Temperance: The Quest for Power and Liberty, 1873-1900 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1981), 5. Stanley Baron, Brewed in America: A History of Beer and Ale in the United States

(Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1962), 3-13, 58-59.

4 Baron, Brewed in America, 14-18.

5 John Allen Krout, The Origins of Prohibition (1925; reis., New York: Russell & Russell, 1967), 31-39. Baron, Brewed in America, 31-51, 56-9. Harry Levine, “The Alcohol Problem in America: From Temperance to Alcoholism,” The British Journal of Addiction 79 (1984), 110-11.

6 The average in 1910 was 2.3 gallons of distilled liquor per capita annually. W. J. Rorabaugh, The Alcoholic Republic: An American Tradition (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979), 5-10. Richard F. Hamm, Shaping the Eighteenth Amendment: Temperance Reform, Legal Culture, and the Polity, 1880-1920 (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1995), 19-21.

7 Maureen Ogle, Ambitious Brew: The Story of American Beer (Orlando, FL: Harcourt, Inc., 2007), 17. Baron, Brewed in America, 179-81. K. Austin Kerr, Organized for Prohibition: A New History of the Anti- Saloon League (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985), 27. Madelon Powers, Faces Along the Bar: Lore and Order in the Workingman’s Saloon,1870-1920 (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1998), 190-92.

8 Richard Briggs Stott, Workers in the Metropolis: Class, Ethnicity, and Youth in Antebellum New York City (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1990), 219-20.

9 Baron, Brewed in America, 242, 257-58. Steven D. Barleen, "‘Rushing the growler’: can rushing and working-class politicization in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era," Labor History 55, no. 4 (October 2014): 519-37, https://doi.org/10.1080/0023656X.2014.948710 (accessed February 9, 2016).

10 Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007),167-78.

11 Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 167. Hamm, Shaping the Eighteenth Amendment, 25.

12 Steven Hahn, A Nation Without Borders: The United States and Its World in an Age of Civil Wars, 1830-1910 (New York: Penguin Random House, 2016), 110. Hamm, Shaping the Eighteenth Amendment, 25.

13 Hahn, A Nation Without Borders, 55-56.

14 Jeanne Boydston, Home and Work: Housework, Wages, and the Ideology of Labor in the Early Republic (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 42-43. Barbara Welter, "The Cult of True Womanhood: 1820-1860," American Quarterly 18, no. 2 (1966), 162. Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 191.

15 Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 604.

16 “Angelina Grimké on Women’ Rights,” in Voices of Freedom: A Documentary History, ed. Eric Foner (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2011), 1:245.

17 Hahn, A Nation Without Borders, 109-10.

18 F.W. Salem, Beer, Its History and Its Economic Value as a National Beverage (1880;

repr. New York: Arno Press Inc., 1972), 11. One Hundred Years of Brewing: A Complete History of the progress made in the Art, Science and Industry of Brewing in the world, particularly during the last Century (Chicago: H.S. Rich & Co., 1901), 226.

19 Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 168.

20 Krout, The Origins of Prohibition, foreword. Hamm, Shaping the Eighteenth Amendment, 25.

21 Peter A. Kopp, Hoptopia: A World of Agriculture and Beer in Oregon’s Willamette Valley (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2016). Samuel A. Batzli, “Mapping United States Breweries,” in The Geography of Beer: Regions, Environment, and Societies, ed. Mark Patterson and Nancy Hoalst-Pullen (New York: Springer, 2014), 33-38.

22 Thomas C. Cochran, The Pabst Brewing Company: The History of an American Business (New York: New York University Press, 1948), 116. Hugh F. Fox, “The Prosperity of the Brewing Industry,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 34, no. 3 (Nov., 1909), 55.

23 Baron, Brewed in America, 257-64. Susanne Freidberg, Fresh: A Perishable History (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009), 93. Gary and Gloria Meier, Brewed in the Pacific Northwest: A History of Beer-Making in Oregon and Washington (Seattle: Fjord Press, 1991), 20, 23-27. One Hundred Years of Brewing, 42, 66-67.

24 Baron, Brewed in America, 241-46, 259-60. Meier and Meier, Brewed in the Pacific Northwest, 21-23. Fox, “The Prosperity of the Brewing Industry,” 51-53.

25 Kerr, Organized for Prohibition, 15, 21. Production went from 13,300 barrels to 33,600 barrels a year. One barrel equaled 31 U.S. gallons. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970, Bicentennial Edition, Part I Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1975), 690-91. Baron, Brewed in America, 258-62.

26 Ernest Hurst Cherrington, The Evolution of Prohibition in the United States of America: A Chronological History of the Liquor Problem and the Temperance Reform in the United States from the Earliest Settlements to the Consummation of National Prohibition (Westerville, OH: The American Issue Press, 1920), 165-68.

27 The National Prohibition Party published the Voice and the Lever while the WCTU published the Union Signal. Hamm, Shaping the Eighteenth Amendment, 22-26. Kerr, Organized for Prohibition, 35-36.

28 White, The Republic for Which it Stands, 516, 554. Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 490-91.

29 Erin M. Masson, “The Women's Christian Temperance Union 1874-1898: Combating Domestic Violence,” William & Mary Journal of Race, Gender, and Social Justice 3, no. 1 (April 1997), 165.

30 Masson, “The Women's Christian Temperance Union 1874-1898,” 180.

31 Hamm, Shaping the Eighteenth Amendment, 24. Abigail Scott Duniway, Path Breaking: An Autobiographical History of the Equal Suffrage Movement in Pacific Coast States, 2nd ed. (Portland, OR: James, Kerns & Abbott Co., 1914), 63-64. Abigail Scott Duniway, “Crusaders, What Think You?,” in “Yours for Liberty:” Selections from Abigail Scott Duniway’s Suffrage Newspaper,” ed. Jean M. Ward and Elaine A. Maveety (Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press, 2000), 106. Ward and Maveety, “Yours for Liberty,” 20.

32 Rush established his opinion that beer and light wines should be used in place of distilled liquors in a 1778 treatise titled Directions for Preserving the Health of Soldiers. His 1811 treatise expanded on his opinions towards alcoholic beverages. Benjamin Rush, An Inquiry into the Effects of Ardent Spirits upon the Human Body and Mind, with An Account of the Means of Preventing and of the Remedies for Curing Them, 6th ed. (New York: Cornelius Davis, 1811), 13. Krout, The Origins of Prohibition, 71-74.

33 Alfred Stillé and John M. Maisch, The National Dispensatory: Containing the Natural History, Chemistry, Pharmacy, Actions and Uses of Medicines, Including those Recognized in the Pharmacopoeias of the United States, Great Britain, and Germany, with Numerous References to the French Codex, 2nd ed. (Philadelphia: Henry C. Lea, 1879), 125-27, 716-18.

34 Salem, Beer, Its History, passim, 128-50.

35 “Medical Temperance Association,” The Journal of the American Medical Association 20, no. 19 (May 13, 1893), 540-41. The American Medical Temperance Quarterly 1, no. 1 (Jul., 1893), https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015069890856;view=1up;seq=7 (accessed May 15, 2017).

36 Fox, “The Prosperity of the Brewing Industry,” 55.

37 “National Prohibitory Constitutional Amendment,” Sixteenth Annual Report of the National Temperance Society and Publication House (New York: The National Temperance Society and Publication House, 1881), 38-39.

38 Caswell reported the votes at 19,172 against and 7985 in favor of the law, or a ratio of thirty-three to thirteen votes against. John E. Caswell, “The Prohibition Movement in Oregon: Part 1, 1836-1904,” Oregon Historical Quarterly 39, no. 3 (Sept. 1938): 260-61.

39 Walter Nugent, Progressivism: A Very Short Introduction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 49.

40 Both the Prohibition Party and the WCTU struggled against national economic concerns, questions about how to operate in the changing political arena, financial issues, and leadership deficiencies. Hamm, Shaping the Eighteenth Amendment, 123-28.

41 The ASL promoted moderate, localized goals with the intention to gradually evolve into national reform, a process that political scientist Ann-Marie Szymanski termed “local gradualism.” Ann-Marie Szymanski, Pathways to Prohibition: Radicals, Moderates, and Social Movement Outcomes (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003), 5.

42 Pete Dunlop, Portland Beer: Crafting the Road to Beervana (Charleston, SC: American Palate, 2013), 38.

43 Day-to-day activities within and associated with saloons were often overshadowed by the folklore of the saloon. Madelon Powers’ study of saloon culture between 1870 and 1920 included folklore and the significance of saloons to local communities. Powers, Faces Along the Bar, passim.

44 Powers, Faces Along the Bar, 13-15. Dunlop, Portland Beer, 38. Lisa McGirr, The War on Alcohol: Prohibition and the Rise of the American State (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2016), 14-15.

45 Royal L. Melendy, “The Saloon in Chicago, II,” American Journal of Sociology 6, no. 4 (Jan., 1901), 433-464. Powers, Faces Along the Bar, 207-226. Perry R. Duis, The Saloon: Public Drinking in Chicago and Boston, 1880-1920 (1983; repr., Urbana, IL: Illini Books, 1999), 8.

46 John A. Watterson, Washington Gladden, Levi Gilbert, and John G. Woolley, “Unity, Persistency, Victory!” A Souvenir Selection of the Anti-Saloon Addresses Delivered at The Annual Congress of the Ohio Anti-Saloon League at Columbus, December 11-13, 1894 (Columbus, OH: The Ohio Anti-Saloon League, Hann & Adair, 1895), 7.

47 Louis M. Hacker, “The Rise and Fall of Prohibition,” Current History 36, no. 6 (Sept. 1, 1932), 662-663. McGirr, The War on Alcohol, 29.

48 Duis, The Saloon, 15-45.

49 Hamm, Shaping the Eighteenth Amendment, 28. Duis, The Saloon, 211-18.

50 Peter H. Odegard, Pressure Politics: The Story of the Anti-Saloon League (New York: Columbia University Press, 1928), 119-21.

51 Duis, The Saloon, 64-67.

52 “Against ‘Blind Tigers,’” The Western Brewer: and Journal of the Barley, Malt and Hop Trades 31, no. 3 (March 1906), 137.

53 Bee Wilson, Swindled: From Poison Sweets to Counterfeit Coffee – The Dark History of the Food Cheats (London: John Murray, 2008), 164.

54 The Jungle began at a wedding party in the backroom of a saloon, and saloons made several other appearances throughout the novel. Upton Sinclair, The Jungle (New York: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1906), especially 95-96.

55 Nugent, Progressivism, 44. James Harvey Young, Pure Food: Securing the Federal Food and Drugs Act of 1906 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989), 221-52.

56 George T. Angell, “Remarks of Mr. Angell,” Journal of Social Science 13 (1 Mar 1881), 130-32. De Lancy Carter, “Beer and Light Wines as Intoxicants,” in Ernest H. Cherrington, ed., Proceedings of the Fifteenth International Congress Against Alcoholism, Held at Washington, D.C., U.S.A, September 21- 26, 1920 (Washington, D.C.: n.p., 1921), 50-53. J.H. Kellogg, “Historical Sketch of the American Medical Temperance Association,” The American Medical Temperance Quarterly 1, no. 1 (Jul., 1893), https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015069890856;view=1up;seq=7 (accessed May 15, 2017), 22.

57 Wilson, Swindled, 164-66. Harvey Levenstein, Revolution at the Table: Transformation of the American Diet (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2003), 147-60.

58 J.T. Pratt, Food Adulteration: or, What We Eat, and What We Should Eat! (Chicago: P.W. Barclay & Co., 1880), 101-102.

59 White, The Republic for Which it Stands, 557.

60 Levenstein, Revolution at the Table, 103-04, 147-60. Wilson, Swindled, 164-66.

61 For bottom fermented beers, like lagers, only barley malt, hops, yeast, and water could be used. Wheat malt was allowed in top fermented beers, and pure beet-cane or invert sugar and coloring substances derived from sugar could be used in special beers. L. Narziss, “The German Beer Law,” Journal of The Institute of Brewing 90, no. 6 (Nov-Dec, 1984), 351.

62 Baron, Brewed in America, 264. “Against ‘Blind Tigers,’” The Western Brewer, 137.

63 Pabst Beer, “Judge Beer By Its True Worth,” advertisement, The Biloxi Daily Herald, January 1, 1907. Pabst Blue Ribbon, "When Company Comes," advertisement, The Morning Oregonian, January 19, 1911. “A Talk on the Advertising of Beer,” The Western Brewer: and Journal of the Barley, Malt, and Hop Trades 40, no. 6 (June, 1913): 245-249.

64 Anti-Saloon League of America, “The Saloon Must Go:” Proceedings Fifteenth National Convention of the Anti-Saloon League of America Twenty Year Jubilee Convention (Westerville, OH: The American Issue Publishing Company, 1913), 35-37. McGirr, The War on Alcohol, 21. Hacker, “The Rise and Fall of Prohibition,” 663-64.

65 Nugent, Progressivism, 83-86. McGirr, The War on Alcohol, 23-24.

66 Raymond W. Smock, ed., Landmark Documents on the U.S. Congress (Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly, Inc., 1999), 284. Amy Mittelman, Brewing Battles: A History of American Beer (New York: Algora Publishing, 2008), 77-79.

67 William G. Ross, World War I and the American Constitution (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 187-88.

68 Hugh F. Fox, “The Saloon Problem,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 32 (Nov., 1908), 532.

69 One Hundred Years of Brewing, 226.

70 Percy Andreae, The Prohibition Movement: In Its Broader Bearings Upon Our Social, Commercial, and Religious Liberties (Chicago: Felix Mendelsohn, 1915), passim.

71 Odegard, Pressure Politics, 67-69. Hacker, “The Rise and Fall of Prohibition,” 664-65.

72 Ross, World War I and the American Constitution, 58. Odegard, Pressure Politics, 166-71.

73 Helen Zoe Veit, Modern Food, Moral Food: Self-Control, Science, and the Rise of Modern American Eating in the Early Twentieth Century (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 14, 35.

74 Odegard, Pressure Politics, 70-72.

75 United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Brewing and Liquor Interests and German Propaganda: Hearings Before a Subcommittee on the Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, Sixty-Fifth Congress, Second Session, Pursuant to S. RES. 307, A Resolution Authorizing and Directing the Committee on the Judiciary to Call for Certain Evidence and Documents Relating to Charges Made Against the United States Brewers’ Association and Allied Interests and to Submit a Report of Their Investigation to the Senate (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1919), 1:3-4. The newspapers of concern were the Washington [D.C.] Times and the New York Evening Mail. Ogle, Ambitious Brew, 178-82.

76 “Is in Germany But Buys Liberty Bonds,” The Western Brewer: and Journal of the Barley, Malt, and Hop Trades 48, no.6 (June 1917), 226.

77 Ross, World War I and the American Constitution, 196. Cochran, The Pabst Brewing Company, 322.

78 Baron, Brewed in America, 311-13. Hacker, “The Rise and Fall of Prohibition,” 665. Smock, Landmark Documents, 309-14. McGirr, The War on Alcohol, 35.

79 Nugent, Progressivism, 90, 116.

80 Nugent, Progressivism, 122.