VOL. 3 EPISODE 6: CULTURE IN THE 1920S

The 1920s was an era of contradictions. We deconstruct the popular image of the Roaring Twenties and examine the tensions at work in American culture. The decade was anything but simple.

INTRODUCTION [0:00-03:03]

In 1931, historian Frederick Lewis Allen published Only Yesterday: An Informal History of the Nineteen Twenties. Just two years removed from the decade, he looked back with familiarity. His lively book included stories of raucous parties where men and women flouted prohibition, smoked cigarettes, and danced late into the night.

“Women” he said, “who a few years before would have gasped at the thought that they would ever be ‘under the influence of alcohol’ found themselves matching the men drink for drink.”

Every Saturday, groups seeking a good time jumped from party to party. Some visited speakeasies, whispering a secret password to gain entrance into the bar. Others rented hotel rooms where men and women lounged on the beds and drank cocktails. At the country clubs, drunk women threw up in the coat closets, men tripped waiters for the fun of it, and young couples drove their cars onto the golf course to find a secluded place to make out.1

These and similar images live on in the public imagination of the 1920s. It was a decade-long party filled with liquor, jazz, and flapper girls before it all came crashing down when the stock market collapsed in the fall of ‘29.

…But this image of the twenties is more nostalgic than historical.2 Wild parties hardly capture the heart of the decade. The Roaring Twenties or Jazz Age or New Era, or whatever we might call it, was filled with tensions and conflicting movements.

Today, our goal is to complicate the image of the decade. We’ll look at a number of parallel stories or themes—misery and escapism, traditionalism and modernism, the changes and the limitations to women’s lives, and racial violence and art. We’ll explore the tensions and contradictions at work in American society.

Whatever the 1920s were, they were not simple.

Let’s dig in.

—Intro Music—

[Welcome to American History Remix, the podcast about the overlooked and underexplored parts of American history. We’re glad you’re here!]

Misery & Escapism

WORLD WAR ONE [03:03-06:03]

The image of the 1920s as an era of exuberance, materialism, and escapism is oversimplified, but not wholly inaccurate. There was an excitement and energy at the time. We’ll get to that. But what is striking is that the period that preceded the “Roaring Twenties” was absolutely awful.

The First World War lasted from 1914 until 1918.

European empires divided themselves into two great alliances. The Central Powers included Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire. The Allies included Britain, France, and Russia.3 Then, the United States joined the Allies in 1917.

Both sides used trench warfare, which is exactly what it sounds like. Soldiers dug trenches in the ground, usually six to eight feet deep, topped with sandbags and barbed wire.

Life in the trenches was a nightmare.

Men spent weeks or even months in the same trench. Soldiers lived in the dirt among the pools of stagnant water, rats, and fleas. In the winter cold, their food and drink would often freeze.4

American soldier Alan Seeger described life in the trenches as “the test of the most misery that the human organism can support.”5

A German trench occupied by British soldiers from the Cheshire Regiment during the Battle of the Somme, 1916. John Warwick Brooke, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Soldiers were surrounded by death and lived under constant threat of attack. If a man peaked out for a view, he could be picked off by an enemy sniper. In battle, men faced tanks and machine guns, new weapons capable of mowing down lines of advancing soldiers.

And they encountered the horror of chemical warfare. The Germans developed mustard gas which, when inhaled, burnt the inside of the lungs. Men died in agony, coughing up blood and gasping for air.

After a battle, “No man’s land,” the place between the two sides, was scarred with craters and filled with mounds of soldiers. The screams and moans of dying men sometimes lasted for days.6

The First World War was like nothing the world had ever seen. Ten million men were killed. Twenty-one million more were wounded, and seven million were left permanently disabled.7

Industrial warfare sucked.

SPANISH FLU [06:03-08:55]

On the heels of the war came an even more deadly catastrophe—the Spanish Flu.

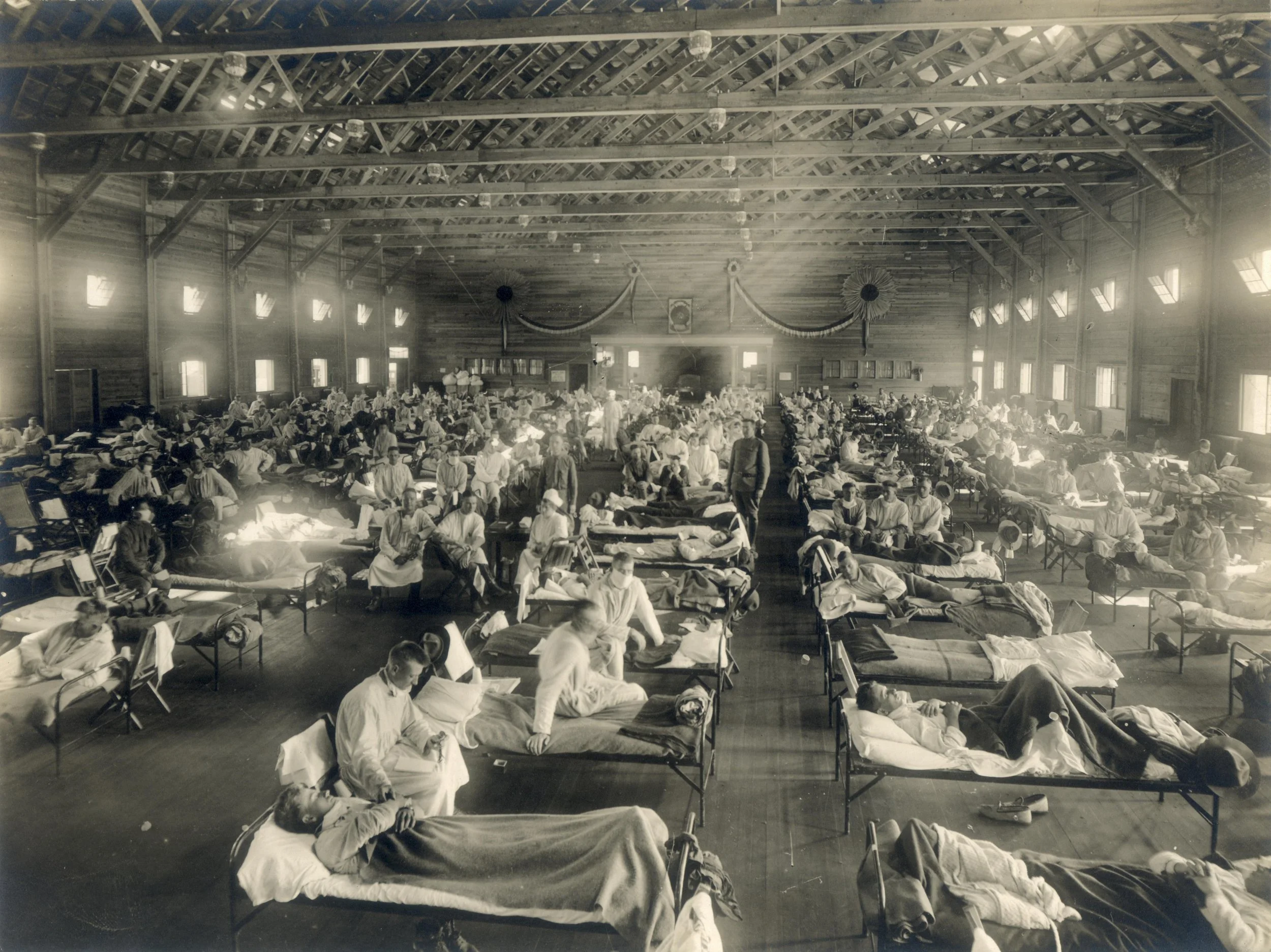

The pandemic roared across the globe in a series of waves. The first in the spring of 1918. The exact origins are unknown, but the first recorded case came in March at an army camp in Funston, Kansas, which is nowhere near Spain. It’s a total misnomer. Soldiers there came down with headaches, fevers, and backaches. The flu then spread across the country. And American soldiers brought the disease to Western Europe.8

Emergency hospital during influenza pandemic, Camp Funston, Kansas. Otis Historical Archives, National Museum of Health and Medicine, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

In June, it spread into Central Europe, Scandinavia, India, Australia, and China. It spread rapidly but the initial mortality rates were low. Then came the second wave.9

In August of 1918, the virus mutated and exploded across the Atlantic world. It hit seaports in Massachusetts, France, and Sierra Leon. Then it spread up the rivers of the Congo and along the Trans-Siberian Railroad. By January 1919, it reached nearly every inhabited place on the planet.10

During a typical pandemic, mortality rates rise across the board but are highest for the young and the elderly. The Spanish Flu was different. It was most deadly for young adults, those in the prime of their lives.11

Victims bled from their noses and coughed up bloody mucus. Before dying, many turned blue. Autopsies later revealed their lungs were swollen, filled with blood and foam.12

Recent estimates suggest that the Spanish Flu killed somewhere between 30 and 40 million people worldwide.13

It killed at least 550,000 Americans. For comparison, every major military conflict of the 20th century—WWI, WWII, Korea, and Vietnam—killed a total of 423,000 Americans. The Spanish Flu killed more than all of them combined, and it did so in one year.14

CONSUMER CULTURE [08:55-10:52]

Historians have traditionally viewed the Roaring Twenties as a response to the death and misery that came before. On its own that explanation is too simple. Many of the trends that culminated in the 20s began well before the war.15 However, there is something to that argument. The 1920s were, in part, a new era of materialism and escapism.

Americans, overall, embraced a consumer culture—a culture based around what a person could buy.

Electricity, mechanization, and the assembly line made factories more efficient and able to produce more. Between 1920 and 1930, industrial production increased by 64%.16 Middle class Americans also benefited from modern convinces like indoor plumbing and electricity. Comfort and leisure were now attainable without having to employ a houseful of servants.17

It became normal for people to buy things with the explicit understanding that those things were disposable. For example, with ready-made clothing available, people could buy new fashions and then throw away old clothes or donate them before they were in need of replacing. Car manufacturers began updating their models every year to encourage drivers to purchase new cars simply to have the latest style.18

By the end of the decade, American spending on leisure and entertainment increased an incredible 300%.19

ENTERTAINMENT [10:52-13:43]

Spectator sports also had growing appeal, in part, because of WWI. Across the country, the military had organized recreational programs that promoted competitive sports as a means to physical fitness.

After the war, college sports grew in popularity as more state-sponsored universities dotted the country. Meanwhile, newspapers, photography, and radio broadcasts provided greater access to sports.20

Football was especially popular. In fact, in 1919 God Almighty founded his own football team—the Green Bay Packers. Boxing was another favorite, but, in the 20s, baseball was king. As one historian said, “Whoever wants to know the heart and mind of America had better learn about baseball.”21

President Calvin Coolidge throwing out baseball at game, 1924. Harris & Ewing, photographer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

In the 1920s, Babe Ruth grew to superstardom as a member of the Boston Red Sox and then the New York Yankees. Ruth introduced a new style of play based on home runs. In 1919, he set a record with 29 home runs in a season. He broke that record in 1920 and then again in 1921. Athletes became the heroes Americans craved after the war. Babe Ruth, boxer Jack Dempsey, and football player Red Grange all became American icons.22

Movies, too, offered Americans a new form of entertainment and escapism.

American filmmaking boomed during the 1910s. After European film companies were devastated by WWI, Hollywood came to dominate the world industry. Twenty to thirty million Americans visited a movie theater each week.23

Many films were stories of far-off fantastical places. The film The Thief of Bagdad from 1924 included flying carpets and mermaids. The films of Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton were light, physical comedies.24

These were all silent films. Text appeared on the screen to inform the audience of dialog or provide other important information. The first full length film with sound was The Jazz Singer, released in 1927. Audiences loved it! Soon, the whole film industry embraced sound.25

THE LOST GENERATION [13:43-15:31]

The 1920s was also a time of artistic innovation. Perhaps the most significant example was a group of writers dubbed The Lost Generation. The group included authors like Earnest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and T.S. Eliot.

These were artists who came of age during WWI. They were disillusioned after witnessing the carnage of the war, and, to them, the post-war era was no more satisfying. They found materialism to be hollow. Many of them relocated to Paris, and their work often criticized modern society. In Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, the wealthy are superficial and empty inside. Gatsby himself is unable to find the peace and love he desires. Likewise, many of Hemingway’s characters struggle to find peace in a post-war society.26

It’s hard not to notice the contrast between the years of misery and the decade of consumerism, escapism, and mass entertainment that followed. War and disease made many people seek material comfort, but others found materialism unsatisfying. It seems that, during the decade, the soul of society was conflicted. And we’re just scratching the surface.

Modernism & Traditionalism

A DIVIDED SOCIETY [15:31-16:51]

“The central paradox of American history,” wrote one historian, “has been the belief in progress coupled with a dread of change.”27 In the 1920s, America was caught between the competing forces of modernism and traditionalism.

Modernism is perhaps more easily seen than explained. Picture skyscrapers dominating the skylines of major American cities, cars filling the streets, the lights and glamour of Hollywood, radios broadcasting jazz and baseball games into American homes.

For decades, America had been becoming an ethnically and religiously diverse, urban society. The twenties were something of a tipping point. The 1920 census found that, for the first time, more Americans lived in cities than in the country.28

In some ways, there was not one America but two—one modern and urban, the other traditional and rural. And that divide touched every part of society.

IMMIGRATION [16:51-18:55]

Immigration to the United States surged during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Those immigrants changed the demographics of the Nation. Rather than coming from northern and western Europe, as most prior immigrants had, the “New Immigrants” came from southern and eastern Europe and were often Catholic or Jewish.

Anglo-American Protestants feared they were losing their cultural prominence and worried that the new immigrants could not be assimilated into American culture. Older stock Americans formed the Immigration Restriction League in 1894, which, big surprise, lobbied to restrict immigration.29

Cartoon printed in The Literary Digest, May 7, 1921 depicting Uncle Sam restricting immigration from Europe in accordance with the First Quota Act. Miscellaneous Items in High Demand, PPOC, Library of Congress, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The group finally found success when Congress passed the First Quota Act of 1921. It limited immigration to 3% per country of origin based on the 1910 census data.30 For easy numbers, let’s say there were 1000 Italians living in America in 1910. In that case, only 30 new immigrants from Italy could enter the US each year.

This law was followed by the National Origins Act of 1924. It lowered the quota to 2% based on the 1890 census. The goal was to weed out recent immigrants but allow those who resembled old stock Anglo-Americans to still enter. A Congressional report claimed that those from Northern and Western Europe possessed “the best material for American citizenship.”31

Thus, the rapid demographic changes inspired a reactionary movement. We’ll see this pattern again.

INTELLECTUAL TRENDS [18:55-23:14]

Another dimension to modernism was the new intellectual trends which reshaped our understanding of the world.

Competing schools of psychology offered various explanations for human behavior. Sigmund Freud’s ideas of sexuality, repression, and the unconscious became well-known to the American public.32

Meanwhile, Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity altered our understanding of the universe and supplanted Newtonian physics. We’re not going to explain relativity, the consistency of the speed of light, and time-dilation here…because we’re a history podcast. But it’s all mind-boggling and awesome, and you should look it up.

Ideas and discoveries like these challenged older understandings of human nature and the physical universe…and that change was uncomfortable to live through. As one contemporary explained, “The more we learn of the laws of [the] universe…the less we shall feel at home in it.”33

As modernist ideas took hold, the preeminence of religion in public life seemed to decline. This change was deeply unsettling. One author reflected, “Both our practical morality and our emotional lives are adjusted to a world that no longer exists.”34

And none of the new ideas were more troublesome than the theory of evolution. Evolution largely divided American Protestants.

On one side were the Modernist Christians who were more willing to embrace modern society and its intellectual trends. Modernists were willing to reinterpret certain passages of scripture based on the findings of modern science.

On the other side were the Fundamentalists who were militantly opposed to modernism. They were dogmatic and committed to what they saw as a literal interpretation of scripture. They also opposed the new sexual norms, dancing, theaters, card playing, and alcohol. In their view, theology and morality went hand in hand. Those loose in their theology would be loose in their morality. Therefore, to the fundamentalists, an attack on their interpretation of the Bible was an attack on civilization itself.35

Throughout the 1910s and ‘20s, the modernists and fundamentalists fought for control of the major Protestant denominations.36

The cultural tensions reached a fever pitch during the Scopes Monkey Trial of 1925. It concerned John T. Scopes and whether he violated Tennessee law by teaching evolution in the classroom. The trial was a media sensation and highlighted the cultural and religious tensions in the country.37

Scopes was found guilty, though the case was later overturned on a legal technicality. However, the results honestly weren’t that important. It was the process that mattered.

You see, in the cross examination, fundamentalists came off looking ignorant and foolish. They won the immediate case but lost in the court of public opinion. Ultimately, modernists got control of the major denominations, and fundamentalists retreated and formed their own churches. And this theological division still exists today.38

THE KLAN [23:14-25:14]

The 1920s also witnessed the rise of the second Ku Klux Klan.

The original Klan died in the 1870s. But, in 1915, a new iteration emerged in Stone Mountain, Georgia. Exact numbers are hard to know, but by 1925 there were probably 5 million members nationwide. The Klan had a presence in cities but was strongest in rural areas.39

The first iteration of the Klan focused its hatred on African Americans. The second Klan had a broader scope. The enemies of America, in their view, were not just Blacks, but also Jews, Catholics, and immigrants—anyone who wasn’t white, Anglo-Protestant. “The Negro is not the menace of Americanism in the same sense that the Jew or the Roman Catholic is a menace,” said Imperial Wizard Hiram Evans.40

Ku Klux Klan members march down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington DC, 1928. See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The reemergence of the Klan was a reaction to modernism. Anglo-Protestants perceived a loss of power and cultural influence. They were confronted with new religious and ethnic communities, changing sexual norms, and the failure of Prohibition. In response, they supported immigration restriction and “racial purity.” They opposed prostitution, gambling, bootlegging, and evolution. The Klan was the first organization to sponsor state laws banning the teaching of evolution in schools.41 The Klan, through violence and intimidation sought a return to an older order.

PROHIBITION [25:14-28:19]

Now, cultural divisions and theological controversies have parallels in other eras. Prohibition, however, was a unique feature of the 1920s, and it illuminates the division within the country.42

Anti-alcohol advocates seemingly won the decades-long fight with the ratification of the 18th Amendment. The sale and manufacture of alcohol became illegal on January 1, 1920. The legal victory, however, accomplished little. Americans found ways to drink.

In the countryside, farmers turned excess grain into moonshine. Tequila crossed the Mexican border into the Southwest. Canadian liquor passed through Detroit or found its way into the US by sea. A stretch of ships anchored in international waters off the East Coast was known as Rum Row. From there, speedboats moved liquor to shore and caravans of vehicles brought booze inland.43

Mobsters offered protection to manufacturers and bribed law enforcement to keep the alcohol flowing. Al Capone oversaw the supply for Chicago. In Brooklyn, Mobster Frankie Yale paid families to maintain stills in their homes.44

Courtrooms and prisons filled-up with alcohol-related arrests. From 1920-22, two-thirds of criminal cases in New York City were Prohibition related. In Virginia, agents recorded over 147,000 arrests.45 On the one hand, this shows the power of the law. On the other, it shows the public’s disregard for it.

Faced with the failure of Prohibition, the Ku Klux Klan stepped up to the plate. “If local officials cannot enforce the law,” said one Klan leader, “we should teach them how.” The Fiery Cross, a Klan magazine said, “The Klan is going to drive bootlegging out of this land.”46

There had once been a strong anti-alcohol coalition. The failure to enforce Prohibition, however, fractured the movement. Many supporters became critics. Some Prohibition advocates took up other causes: anti-evolution or anti-jazz. Contemporaries eventually came to view Prohibition as just one of many traditionalist movements which pitted “ignorant ruralites against progressive city dwellers.”47

POLITICAL DIVIDE [28:19-30:40]

All these factors shaped the politics of the decade as well.

The Republican Party was the dominant party in the twenties, due in part to the fact that Democrats were divided among themselves. The regions of the South and West were more rural, white, and Protestant. The northern branch of the party was more urban and diverse. It included immigrants, Catholics, and Jews.

At the 1924 Democratic Convention, the party struggled to even nominate a presidential candidate. Rural constituents favored William Gibbs McAdoo. Urban constituents favored Al Smith, who was Catholic, the son of Irish immigrants, and represented the diversity rural members wanted to avoid. Literal fistfights broke out, and it took 103 ballots to reach a candidate. Ultimately, the sides compromised and nominated John W. Davis…who lost the election to Republican Calvin Coolidge in the fall.48

In the 1928 election, Al Smith actually won the Democratic nomination, but he lost soundly to Republican Herbert Hoover. Hoover was old stock American. Smith still seemed to represent everything traditionalists hoped to avoid. It wasn’t just that Al Smith was Catholic, though that was part of it. He was, as one contemporary described, “New York minded.”49

Change begets change. Some celebrate it, some resist it. As America modernized, many fought to preserve the culture and the traditions they had known before. The ensuing cultural tensions shaped everything from immigration policy to debates over religion, Prohibition, and national politics.

Traditional & “New Woman”

HOME & WORK [30:40-31:55]

The 1920s are often called a “New Era,” and the decade produced a “New Woman.” Indeed, the cultural shifts of the decade are perhaps best seen in the experiences of women.

The 19th Amendment, ratified in 1920, gave women the national right to vote and thus granted them equal political rights as men. Women also made up a growing portion of the labor force. While most worked as domestic servants, in sales, or as office clerks, pioneering women entered a range of professional fields.50

Gender expectations were changing in the home as well.

Those women who entered professional careers in the late 1800s usually did not marry. By the 1920s, the New Woman rejected the choice. “We all determined to combine marriage and careers, somehow,” wrote Nora Stanton.51

SEX [31:55-34:50]

The marriages they wanted would have to look different. The New Woman would not merely seek economic stability, but companionship.52

Sex, too, took on a new importance in marriage. In the Victorian era, the prevailing belief was that men were sexual and passionate, but women were gentle and chaste. Sex for a woman was not a need, it was a duty.53

The young women of the 1920s shed this older sensibility. Society came to acknowledge female sexual desire and recognize sex as an important part of a happy marriage.54

Middle class women increasingly used contraception. They could now limit the size of their families and enjoy sex without the fear of pregnancy. A survey a generation later found that, for many women, it became easier to achieve sexual pleasure.55

The customs outside of marriage changed as well.

One survey of high school students at the time found that about 50% engaged in what they called “petting.” Essentially, making out and groping each other. Fun stuff, but scandalous at the time. “None of the Victorian mothers….had any idea how casually their daughters were accustomed to be kissed,” wrote F. Scott. Fitzgerald.56

Promiscuity was still shunned, but younger Americans accepted sex within a committed relationship and as a prelude to marriage. These changes were significant. A survey of middle-class women in 1938 found that 74% of those born before 1900 were virgins when they got married. Among those born after 1910, less than 32% were virgins when they got married.57

Likewise, female sexuality appeared in advertisements and films, demonstrating a greater public openness regarding sex.58

Perhaps no image better captures this change than that of the flapper girl. Flapper girls wore short skirts and loose-fitting clothes, exposing their legs and shoulders. They wore their hair short, wore make up, smoked cigarettes, drank alcohol, and went dancing in jazz clubs.59

Victorian fashion, circa 1895-1899. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Flapper fashion, 1927. See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

It was a shock to those raised in the Victorian era, where women wore long dresses, kept their hair long, and wore over 29 layers of undergarments. The times were changing.

LIMITS TO THE CHANGE [34:50-37:15]

However, there were limits to the change, and the new environment created new problems.

While the new mores and greater sexual freedoms were shocking, they actually brought about minimal change to the daily life of women in America. A career would more fundamentally alter gender expectations and challenge the assumption that a woman was solely responsible for the home.60

And that was where change occurred the least. Between 1920 and 1930, the number of female lawyers doubled, but they still comprised only 2% of the field.61

Though women in the 1920s could engage in politics and could join the labor force, Americans still believed that a woman’s primary duty was in the home. A woman might work while she was young and single, but she would still eventually settle down.62

Additionally, the new gender roles could be difficult to navigate. One young woman complained to an advice column that while she enjoyed “petting,” she was also concerned that men only wanted to marry women they could respect for not “petting.”63

The new norms weren’t fully liberating, they presented their own challenges.

Sometimes, husbands were supportive of their wives’ careers. Amy Beach was a concert pianist. Though that career ended when she married, her husband encouraged her to begin a career as a composer, which she did successfully. Other times, a husband could be supportive of his wife’s career in theory but found it difficult to adjust in practice. The progressive reformer Frederic C. Howe wrote regretfully that, while he favored women’s rights generally, in his own marriage he still wanted “my old-fashioned picture of a wife rather than an equal partner.”64

Older expectations did not disappear overnight.

CONSUMER SOCIETY [37:15-38:28]

The growing consumer society was another complicating factor. Businesses, advertisers, and Hollywood embraced the New Woman. But that meant that youth and beauty and sexuality were monetized and commercialized. In 1920, there were 5000 beauty shops in the country. By 1930, there were 40,000. This environment fostered a new stereotype that women were materialistic and superficial—youth and beauty were all that mattered. For example, in the 1927 film Ladies Must Dress, a woman wins back her man by getting a makeover.65

Many in the Victorian era had failed to recognize female sexual desire. Many in the 1920s acted as though women only wanted to be young, pretty, and sexually desirable. One problem was replaced with another.

GENERATIONAL DIVIDE [38:28-39:58]

Finally, not all women approved of the cultural changes. The suffragists of the late 1800s disapproved of the New Woman. Some viewed the sexual liberation of the twenties as an “abuse of new freedom” and a distraction from social reform.66

To the older generation, the New Woman’s material interests were trivial and selfish. Charlotte Perkins Gilman offered her analysis, “This is the woman’s century, the first chance for the mother of the world to rise to her full place, her transcendental power to remake humanity, to rebuild the suffering world—and the world waits while she powders her nose.”67

Society was changing, but it was not a complete break from what came before. There was room for the New Woman to exercise some independence and find some sexual satisfaction within a romantic relationship. But Americans still held that a woman’s primary role was as a wife and mother.68

Racial Violence & Art

THE GREAT MIGRATION [39:58-41:12]

Now we reach our final theme—the paradox of racial violence and art.

In the early 1900s, the African American community lived mostly in the rural South. But between 1916 and 1918, 450,000 African Americans moved to the urban North. They settled in cities like Chicago, New York, and Pittsburgh. It was the beginning of a generation-long movement called The Great Migration.

There were several motives for the move. One was for parents to provide a better life and education for their children. Economics was another factor. Most African Americans in the South worked as sharecroppers who lived in poverty even in the best of times. But the manufacturing demands during WWI created new jobs. African Americans moved north to fill those positions.69

LYNCHING [41:12-43:50]

But, whether in the North or South, African Americans lived under the threat of mob violence.

Lynching is the killing of someone outside of the justice system, usually by hanging. A person would be accused of some offense, and then a mob would form. Law enforcement was often complicit with lynch mobs. In 1927 in Mellwood, Arkansas, African American Owen Flemming defended himself when his white employer pulled a gun on him. A mob then formed and caught Flemming. Rather than hold a trial, the local sheriff told them, “I’m busy, just go ahead and lynch him.”

Between 1877 and 1950, more than 4000 African Americans were killed in lynchings.

The story of Irving and Herman Arthur is especially horrific. The brothers lived in Paris, Texas and worked for white farm owners. In 1920, they attempted to quit their jobs, but their employers tried to force them back to work at gunpoint. After the brothers fled, the owners claimed the men had injured them….somehow.

Irving and Herman were arrested. A mob of 3000 people gathered. They tortured the brothers and then burnt them to death. Their bodies were chained to a car, drug through town, and dropped off outside the courthouse.

Meanwhile, their sisters were taken into police custody, supposedly for their own safety. The girls were gang raped inside the goddamn police station. No charges were ever brought against the white mob.

Soon afterwards, the Arthur family fled from Texas to Chicago. They were part of The Great Migration. This raises an important question. Perhaps calling it a “migration” is misleading? Perhaps it would be more accurate to say that it was, at least in part, the story of refugees fleeing terrorism.70

The Arthur family arrives in Chicago two months after two of their sons were lynched in Paris, Texas. Published in The Chicago Defender on September 4, 1920, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

TULSA RACE MASSACRE [43:50-46:58]

Let’s look at another story.

Greenwood was an affluent Black neighborhood in Tulsa, Oklahoma. It was home to nearly ten thousand African Americans and was a pocket of Black prosperity. There were several Black-owned businesses, a library, multiple churches, and two newspapers.

The white community of Tulsa was resentful of Greenwood’s prosperity.

On May 30th, 1921, Dick Rowland, a black nineteen-year-old shoe shiner shared an elevator ride with a white woman named Sarah Page. It’s unclear exactly what happened on that ride, accounts differ, but the most common explanation is that Rowland stepped on the shoe of Sarah Page, and she let out a scream. But a rumor spread that he had attempted to rape Page, and Rowland was taken into police custody.

The following day, a group of several hundred whites gathered outside the courthouse and demanded that they turn him over to the crowd. The authorities refused. Denied the opportunity to lynch Rowland, the crowd grew even angrier.

Meanwhile, black residents of Greenwood assembled at the courthouse to protect Rowland. At one point, a white man tried to take the gun of a black man. Somewhere in the skirmish, a shot was fired. We don’t know who fired first. But what followed was a massacre.

The Tulsa Police decided to deputize members of the lynch mob, giving them weapons and temporary police authority. Their instructions were to “get a gun and get a nigger.” The mob, as instructed, turned against the entire Black community. Cars of white men drove past Black homes and shot residents at random. At daybreak, the white mob, now thousands strong, poured into Greenwood. They looted homes and businesses. The Black community fought to protect their homes and property, but they were simply outnumbered.

Tulsa in flames during the race riot, 1921. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The mob then set fire to the buildings and homes and burnt Greenwood to the ground. In the end, 35 city blocks were a smoldering ruin and as many as 300 people were killed.71

Yet, no one was ever arrested.

THE BLUES [46:58-51:00]

Yet, amidst the constant threat of violence, African American music and art flourished.

Let’s talk about the blues.

As a distinct genre, it came into its own among the first generations of Southern Blacks born into freedom. The first blues musicians were itinerate performers of the Mississippi Delta. They played on the roadsides, in taverns, brothels, and railroad stations.

The first man to popularize the blues was composer W.C. Handy, who published the song “St. Louis Blues” in 1912. Handy first heard the blues from a man singing at a Mississippi train station. But he recognized the sound—it was similar to something he had heard as a boy growing up in Alabama.72

Around the turn of the century, a New Orleans fiddle player was asked where the blues came from. “The blues?” he answered, “Ain’t no first blues! The blues always been.”73

Blues music has several distinct characteristics. The singing is emotional, using groans, shouts, and falsetto.74 The lyrics are often sad, telling stories of misery, death, and loneliness. It’s honest and cathartic. Lyrically, it has an AAB structure. The singer sings a line, repeats it, then the final line of the verse is different. For example:

Woke up this morning, feeling sad and blue,

Woke up this morning, feeling sad and blue,

Didn’t have no body to tell my troubles to.75

There is also space in the verse that allows for a call and response. Between each line the singer can improvise, often adding words like “lord” or “yes, ma’am.”76

Typically, the blues uses three chords. The I, IV, V chords. Even if you don’t know music theory, you’ll still recognize how they sound.77 [PLAYS CHORDS].

The chord structure comes from the European musical tradition, but the blues is not bound by European harmony. While in the western tradition we have 12 notes, blues musicians use “blue” notes, pitches above or below standard tuning. Singers slide between notes, and guitar players bend the strings to reach notes between the frets.78 [PLAYS NOTES]

This, of course, was just a typical structure. It was folk music and flexible. It could be adapted by each performer as they saw fit.79

Now, all of these characteristics—this sort of singing, the call and response, and the AAB structure, were all used by the musicians of West Africa. This means that the musical traditions of Africa were preserved and passed down within the slave community for centuries. When those traditions were superimposed upon European chords, you got the blues— “the blues always been.”80

RAGTIME [51:00-53:00]

In the 1890s, another African American genre emerged called ragtime.

It’s piano music distinguished by its rhythmic complexity. Ragtime uses a musical technique called syncopation which accents the off beats. For example, a typical rhythm might have four beats. 1-2-3-4. But there is space between those beats. 1-AND-2-AND-3-AND-4-AND.

Emphasizing these beats makes the rhythm feel ragged—hence the name “ragtime.” Syncopation is not new. But ragtime musicians took it and ran wild, creating music that was energetic and rhythmically complex.81

The pianist and composer Scott Joplin was the king of ragtime. His 1899 song “Maple Leaf Rag” is the quintessential example of the genre.82 Here’s a taste. [PLAYS SONG]

These highly syncopated rhythms were also used by the musicians of West Africa. Joplin himself refuted the idea that ragtime was new. “There has been ragtime in America ever since the Negro race has been here,” he said.83

BRASS BANDS [53:00-54:10]

At the turn of the century, cities across the country, both big and small, often had their own musical ensembles. They usually had 12-14 members, a trumpet, cornet, trombone, clarinet, drums, and perhaps a tuba. They performed for local dances, at funerals, or on election day. They played marches, hymns, and popular songs.84

Now, in New Orleans something peculiar happened. The African American ensembles incorporated stringed instruments. There’d be violin, guitar, a bass, plus a cornet, clarinet, trombone, and drums. The younger musicians there also incorporated elements of ragtime and the blues. Their music was really a collective improvisation. They would play a song’s melody once and then improvise upon it, creating complex, polyphonic music.85

JAZZ [54:10-54:57]

When the brass/string bands of New Orleans incorporated the harmonic complexity of the blues and the rhythmic complexity and energy of ragtime, do you know what you get? You get jazz.86 [PLAYS SONG]

King & Carter Jazzing Orchestra, 1921. From the Robert Runyon Photograph Collection, courtesy of The Center for American History, the University of Texas at Austin, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

That was “Jelly Roll” Morton. He and other jazz pioneers like Louis Armstrong and Joseph “King” Oliver hailed from New Orleans before they brought their music to cities like Chicago and New York.87

HARLEM RENAISSANCE [54:57-57:00]

Harlem, a neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, was one of the centers of The Great Migration. There, piano player Duke Ellington played for a nightclub called the Cotton Club, which catered to white audiences and helped further spread the popularity of jazz.88

In fact, during the twenties, the whole neighborhood hosted such a thriving Black artistic community that it’s called the Harlem Renaissance.

The list of artists living and working in the neighborhood is staggering. They include poets like Langston Hughes and Countee Cullen. Novelists like Claude McKay and Zora Neale Hurston and writer and philosopher Alain Locke, who edited a definitive collection of writings called The New Negro.89

Their work celebrated Black culture. They drew on racial motifs and invoked Africa in their work. They saw their work as contributing to the struggle against racial discrimination. Langston Hughes wrote “We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame.”90

The 1920s are sometimes called the “Jazz Age.” The term captures the exuberance of the era. But that joyful, energetic music was created by a community largely impoverished and under constant threat of violence. Lynching and Tulsa alongside Jazz and the Harlem Renaissance—the African American experience captures well the paradoxes of the decade.

CONCLUSION [57:00-58:28]

The 1920s were a time of contradictions. It was a new era of material prosperity, modernism, a “New Woman,” and a “New Negro.” But materialism was largely a reaction to misery, modernism contended with traditionalism, the New Woman still had limited opportunities, and the New Negro still faced mob violence.

Every era has its own tensions and contradictions, but the 1920s were especially strange and fascinating.

Thanks for listening.

[American History Remix is written and produced by Will Schneider and Lyndsay Smith. For the latest updates, be sure to follow us on Instagram and Threads. Check out our website for episode transcripts, recommended reading, and resources for teachers. That’s AmericanHistoryRemix.com.]

REFERENCES

Allen, Frederick Lewis. Only Yesterday: An Informal History of the 1920's. 1931. Reprint, New York: Perennial Classics, 2000.

Ashby, LeRoy. With Amusement for All: A History of American Popular Culture since 1830. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2006.

Barkley, Elizabeth F. Crossroads: Popular Music in America. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 2003.

Carter, Paul A. The Twenties in America, 2nd ed. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley-Blackwell, 1975.

Chafe, William H. The American Woman: Her Changing Social, Economic, and Political Roles, 1920-1970. New York: Oxford University Press, 1974.

Crosby, Alfred W. America's Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918. 2nd ed. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Dumenil, Lynn. The Modern Temper: American Culture and Society in the 1920s. New York: Hill and Wang, 1995.

Gordon, Linda. The Second Coming of the KKK: The Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s and the American Political Tradition. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2017.

Howard, Michael. The First World War: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Jacobson, Matthew Frye. Whiteness of a Different Color: European Immigrants and the Alchemy of Race. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999.

Klein, Maury. Rainbow’s End: The Crash of 1929. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Magee, Jeffery. “Ragtime and Early Jazz.” In Cambridge History of American Music, edited by David Nicholls, 388-417. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Marsden, George M. Fundamentalism and American Culture. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Matthews, Jean V. The Rise of the New Woman: The Women's Movement in America, 1875-1930. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2003.

McGirr, Lisa. The War on Alcohol: Prohibition and the Rise of the American State. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2016.

Merriman, John. A History of Modern Europe: From the Renaissance to the Present. 3rd ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2009.

Patterson, K. David and Gerald F. Pyle. "The Geography and Mortality of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic." Bulletin of the History of Medicine 65, no. 1 (Spring 1991):4-21, https://www.jstor.org/stable/44447656 (accessed June 22, 2024).

Pegram, Thomas R. “Hoodwinked: The Anti-Saloon League and the Ku Klux Klan in 1920s Prohibition Enforcement.” The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 7, no. 1 (2008): 89–119, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537781400001742 (accessed October 9, 2024).

Rauchway, Eric. The Great Depression and the New Deal: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Rorabaugh, W.J. Prohibition: A Concise History. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Southern, Eileen. The Music of Black Americans: A History. New York: W.W. Norton, 1971.

Strasser, Susan. Waste and Want: A Social History of Trash. New York: Metropolitan Books, 1999.

NOTES

1 Frederick Lewis Allen, Only Yesterday: An Informal History of the 1920's (1931; repr., New York: Perennial Classics, 2000), 95-96.

2 Allen admits that such stories were “of course exceptional and in many communities they never occurred.” Allen, Only Yesterday, 96.

3 Michael Howard, The First World War: A Very Short Introduction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 29.

4 John Merriman, A History of Modern Europe: From the Renaissance to the Present, 3rd ed. (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2009), 892-93.

5 “Alan Seeger on World War I (1914; 1916),” The American Yawp Reader, accessed June 22, 2024, https://www.americanyawp.com/reader/21-world-war-i/alan-seeger-on-world-war-i-1914-1916/.

6 Merriman, A History of Modern Europe, 892-95.

7 Merriman, A History of Modern Europe, 923.

8 Alfred W. Crosby, America's Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918, 2nd ed. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 19-25. K. David Patterson and Gerald F. Pyle, “The Geography and Mortality of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 65, no. 1 (Spring 1991), 5-7.

9 Patterson and Pyle, “The Geography and Mortality of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic,” 8.

10 Crosby, America’s Forgotten Pandemic, 37. Patterson and Pyle, “The Geography and Mortality of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic,” 10-13.

11 Crosby, America’s Forgotten Pandemic, 21.

12 Crosby, America’s Forgotten Pandemic, 7-8.

13 Patterson and Pyle, “The Geography and Mortality of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic,” 19.

14 Crosby, America’s Forgotten Pandemic, 206-07.

15 Lynn Dumenil, The Modern Temper: American Culture and Society in the 1920s (New York: Hill and Wang, 1995), 9-10.

16 Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 58-59.

17 Susan Strasser, Waste and Want: A Social History of Trash (New York: Metropolitan Books, 1999), 170-72.

18 Strasser, Waste and Want, 187-97. Christine Frederick, Selling Mrs. Consumer (New York: Business Bourse, 1929), https://archive.org/details/sellingmrsconsum00fredrich/page/n7/mode/2up?ref=ol&view=theater (accessed June 3, 2024). Frederick writes on obsolescence, including the role color plays, on pages 245-55.

19 Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 77.

20 LeRoy Ashby, With Amusement for All: A History of American Popular Culture since 1830 (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2006), 177-81.

21 Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 77. Quote from Maury Klein, Rainbow’s End: The Crash of 1929 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 19.

22 Ashby, With Amusement for All, 179-80, 184-86. “Babe Ruth #3,” MLB, accessed October 9, 2024, https://www.mlb.com/player/babe-ruth-121578.

23 Ashby, With Amusement for All, 186-97. Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 77.

24 Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 91-93.

25 Ashby, With Amusement for All, 216-18.

26 Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 149-52.

27 Paul A. Carter, The Twenties in America, 2nd ed. (Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley-Blackwell, 1975), 8.

28 Eric Rauchway, The Great Depression and the New Deal: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 74-75.

29 Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 204-05.

30 Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 207.

31 Matthew Frye Jacobson, Whiteness of a Different Color: European Immigrants and the Alchemy of Race (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999), 83.

32 Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 146-47.

33 Dumenil, The Modern Temper,148. Quote from Carter, The Twenties in America, 8.

34 George M. Marsden, Fundamentalism and American Culture, 2nd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), 3.

35 Marsden, Fundamentalism and American Culture, 4, 20, 36, 163. William E. Ellis, “The Fundamentalist-Moderate Schism over Evolution in the 1920’s,” The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 74, no. 2 (April 1976), 112.

36 Marsden, Fundamentalism and American Culture, 164.

37 Marsden, Fundamentalism and American Culture, 184-87.

38 Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 189-90. Marsden, Fundamentalism and American Culture, 19-94.

39 Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 236-25.

40 Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 235. Quote from Linda Gordon, The Second Coming of the KKK: The Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s and the American Political Tradition (New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2017), 41.

41 Thomas R. Pegram, “Hoodwinked: The Anti-Saloon League and the Ku Klux Klan in 1920s Prohibition Enforcement,” The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 7, no. 1 (2008), 89. Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 235, 241. Gordon, The Second Coming of the KKK, 51.

42 Carter, The Twenties in America, 71-72.

44 Lisa McGirr, The War on Alcohol: Prohibition and the Rise of the American State (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2016), 53-57. Rorabaugh, Prohibition, 65, 69.

45 Rorabaugh, Prohibition, 87. McGirr, The War on Alcohol, 78.

46 Rorabaugh, Prohibition, 63.

47 Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 245-46.

48 Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 201-202.

49 Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 232. Carter, The Twenties in America, 78.

50 Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 99-100, 114.

51 Jean V. Matthews, The Rise of the New Woman: The Women's Movement in America, 1875-1930 (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2003), 98-99.

52 Matthews, The Rise of the New Woman, 98.

53 Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 131.

54 Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 131.

55 William H. Chafe, The American Woman: Her Changing Social, Economic, and Political Roles, 1920-1970 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1974), 95. Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 136.

56 Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 136-37. Quote from Allen, Only Yesterday, 78.

57 Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 136. Chafe, The American Woman, 94-95.

58 Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 132-34.

59 Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 134-35.

60 Chafe, The American Woman, 96-97.

61 Matthews, The Rise of the New Woman,178-79.

62 Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 127.

63 Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 137.

64 Matthews, The Rise of the New Woman, 101-102.

65 Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 141-43. “Ladies Must Dress,” The Progressive Silent Film List, Silent Era, last modified December 24, 2024, http://www.silentera.com/PSFL/data/L/LadiesMustDress1927.html.

66 Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 138.

68 Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 141.

69 Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 284-85.

70 Information for lynching section from: “Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror,” Equal Justice Initiative, accessed December 27, 2024, https://lynchinginamerica.eji.org/report/. “Early Chicago: The Great Migration,” WTTW, accessed December 27, 2024, https://interactive.wttw.com/dusable-to-obama/the-great-migration.

71 Information for Tulsa Race Massacre section from: “Tulsa Race Massacre,” Oklahoma Historical Society, accessed December 27, 2024, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=TU013. “1921 Tulsa Race Massacre,” Tulsa Historical Society and Museum, accessed December 27, 2024, https://www.tulsahistory.org/exhibit/1921-tulsa-race-massacre/.

72 Eileen Southern, The Music of Black Americans: A History (New York: W.W. Norton, 1971), 332, 337.

73 Southern, The Music of Black Americans, 332-33.

74 Elizabeth F. Barkley, Crossroads: Popular Music in America (Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 2003), 101. Southern, The Music of Black Americans, 335.

75 Southern, The Music of Black Americans, 333-34.

76 Barkley, Crossroads, 101. Southern, The Music of Black Americans, 335.

77 Southern, The Music of Black Americans, 335. The chords are usually dominant 7th chords, but we’re keeping our music theory explanation simple.

78 Southern, The Music of Black Americans, 191-92. Barkley, Crossroads, 104.

79 Southern, The Music of Black Americans, 335.

80 Southern, The Music of Black Americans, 191-92. Barkley, Crossroads, 104.

81 Jeffery Magee, “Ragtime and Early Jazz,” in Cambridge History of American Music, ed. David Nicholls (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 389.

82 Southern, The Music of Black Americans, 318.

83 Magee, “Ragtime and Early Jazz,” 389.

84 Southern, The Music of Black Americans, 340-43.

85 Barkley, Crossroads, 122, 125. Southern, The Music of Black Americans, 356, 358, 377.

87 Magee, “Ragtime and Early Jazz,” 409.

88 Barkley, Crossroads, 130-32.

89 Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 160-61.

90 Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 162. Quote from "Langston Hughes, 1902-1967," Poetry Foundation, accessed October 9, 2024, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/langston-hughes.