VOL. 3 EPISODE 7: THE GREAT DEPRESSION & DUST BOWL

The Great Depression sucked, the Dust Bowl made it even worse. We discuss how American greed destroyed both the economy and the land. Buckle up.

INTRODUCTION [00:00-03:50]

In the early 1920s, American real estate developers sought to make Florida a travel destination. They dredged swamps, constructed canals, built new cities, homes, resorts, and hotels. Then, they advertised it as America’s version of Europe’s Riviera. Their ad campaign worked. The region boomed, and the population of Miami doubled.

Miami Biltmore Hotel during its opening month in January, 1926. Florida Memory, State Library and Archives of Florida, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Speculators swarmed the state, quickly purchased land, and caused property prices to soar. The market peaked in 1925, but it had grown so fast it inflated the actual value of the land. Then, the bubble burst and property values collapsed. Speculators had been so eager to buy land that many purchased it with only 10% down, hoping to recoup the cost when they later resold it. But now, with prices spiraling downwards, many were left with huge debts on land worth a fraction of what they paid.1

Then, while they were down, the natural environment decided to kick Floridians in the balls.

In the early morning of September 18th, 1926, the Great Miami Hurricane hit South Florida. The storm flooded the region. The sea levels swelled to 11 feet over their high tide mark while winds over 150 miles an hour whipped through the state. The storm destroyed 4700 houses, displaced 25,000 people, killed nearly 400, and injured another 6000. The hurricane destroyed much of the property that developers had constructed in the real estate boom.2 And it led to the collapse of banks across both Florida and neighboring Georgia.3

Looking east on Flagler St. from 13th Ave in Miami, 24 hours after the hurricane of September 18, 1926. Verne O. Williams, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Economic collapse and an environmental disaster proved a devastating combination, but it was just a prelude of what was to come.

The 1920s were an era of growth. The thriving economy offered new forms of comfort and convenience. It’s why we call them the Roaring Twenties. But that decade of exuberance came crashing down in the fall of 1929 as America entered the Great Depression.

Then, while reeling from the economic collapse, farmers in the Great Plains were struck by an ecological disaster—the Dust Bowl. The land itself was dying and blowing away in the wind. Monstrous storms of dust swept across the Plains, swallowed whole towns, and blocked out the sun.

Today we are going to tell the story of those two disasters—one economic, one ecological—and how the Nation struggled to endure both. Though very different on the surface, both were in part caused by the same thing—America’s blind belief in progress and unlimited growth.

Let’s dig in.

—Intro Music—

[Welcome to American History Remix, the podcast about the overlooked and underexplored parts of American history. We’re glad you’re here!]

WORLD WAR ONE & WHEAT [03:50-07:06]

Both of our stories begin with World War One.

The First World War, fought between 1914 and 1918, killed 10 million soldiers. Another 20 million were wounded. And it destroyed $300 billion of the world’s wealth.4

And if that wasn’t bad enough, it also drove up the price of wheat. The war disrupted the global grain supply. Hungry Europeans turned to American farmers on the Great Plains. The US government printed flyers proclaiming “Plant more wheat! Wheat will win the war!”

And so, Americans rushed to fill the need. In 1917, farmers from Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Colorado, and Texas harvested 45 million acres and exported 133 million bushels of wheat. In 1919, they harvested 74 million acres, which yielded 952 million bushels. Meanwhile, prices soared. American wheat in 1919 sold for over twice the amount it had in 1914.5

Farmers were able to expand their production thanks to mechanical agriculture. Machines revolutionized farming.

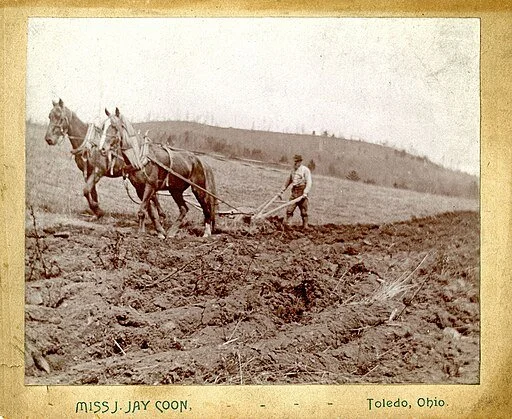

Farmers on the Plains began using steam-powered tractors at the opening of the century, then switched to lighter, gas-powered machines in the 1910s. The combine was pulled by a tractor and cut a 16-foot swath through a field of wheat. It separated the grain and poured it into the bed of a truck. The disk plow had a vertical beam with a series of plates which, when pressed to the ground, stirred up the top layer of soil to increase water absorption and kill weeds.6

In 1830, a farmer plowing with a mule would spend nearly 60 hours harvesting an acre of grain. By 1930, an acre could be plowed in 3-6 hours.7

Farmer plowing a field with a traditional plow, circa 1890. Toledo-Lucas County Public Library, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Ford tractor demonstration, between 1921 and 1922. National Photo Company Collection, Library of Congress, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The machines opened up new farmland. Farmers used to grow food to feed the animals which helped them farm. But as horses and mules were replaced by tractors, perhaps 30 million acres of land on the Great Plains opened up to grow cash crops.8

One large farm owner borrowed the arguments of Henry Ford and claimed that modern prosperity was only possible through “large-scale, collective, group, specialized, departmentalized activity.” In other words, industrial farming.9

Oh, to be a wheat farmer in 1919! Must have been pretty sweet. But…it wasn’t great for everyone.

1920s ECONOMY [07:06-09:29]

As often happens after a war, the economy entered a recession. Two million servicemen returned home and flooded the job market. At the same time, the government’s wartime contracts with private businesses expired. Those problems were magnified by post-war inflation. A recession began in 1920 and lasted into the following year. 100,000 companies went bankrupt, and 4 million people were unemployed.10

Soon, however, the urban economy recovered and, for most of the decade, America had a seemingly robust manufacturing economy.

The auto industry best demonstrates the growth.

Henry Ford invented the assembly line in 1914 and revolutionized car production. By 1928, his factory could produce 6400 new cars in a day.11

Photo of the Ford Motor Company assembly line that accompanied an interview of Henry Ford in The Literary Digest, January 7, 1928. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Car manufacturing doubled in the decade, as auto companies began selling cars on credit. By 1929, there were 23 million cars for 123 million Americans.12

Like the railroads had done in the 19th century, the growth of auto manufacturing fueled other related industries such as gasoline, rubber, steel, and glass. Cars also offered Americans a sense of freedom and symbolized American achievement and progress.13

And they were far from the only luxury Americans purchased at the time. As electricity became more common, so did electric appliances, as did radios and records, cosmetics, and books. Americans simply purchased more material goods than they had in any prior generation.14

And they grew more comfortable acquiring debt in order to enjoy the luxuries of the day.15

OVERPRODUCTION OF WHEAT [09:29-11:09]

But while the cities were booming, rural Americans were now struggling. After the Great War ended, European farmers resumed work in their fields and international demand for American wheat declined.16 American farmers found they had overproduced wheat. Overproduction and decreased demand created a surplus, which caused the price of wheat to plummet.

In 1920, the average price per bushel of wheat was $2.16. By 1921, that price was cut by more than half, down to only $1.03. Throughout the 1920s and 30s, the average wheat price never rose above $1.50.17

Large farmers were better able to weather the storm. Ida Watkins was known as the “Wheat Queen” of Kansas. In 1928, she harvested 2500 acres of wheat. Dissatisfied with the price, she stored 50,000 bushels until the following year.18 Small farmers didn’t have the same capacity. Many went into debt trying to keep up with such large competitors. Facing declining prices, they planted even more, plowing millions of acres and tripling the output of wheat over the 1920s…which only added to the problem.19

CONSUMPTION & PROGRESS [11:09-12:49]

Regardless of international demand, American farmers were driving full speed towards a cliff. They sought to maximize their production at all costs, pursuing a dream of unlimited growth.20

It hadn’t always been that way. In the opening years of the 19th century, most Americans had sought self-sufficiency—to own their land and be free of debt.21

During the Industrial Revolution, Americans altered those traditional values. Many went to work for wages, factories produced as many products as possible, and merchants promoted them to the public. As one historian put it, “a multitude of goods were produced to satisfy needs that no one knew they had.”22

Self-sufficiency gave way to consumption as more Americans sought comfort, convenience, and the social status that came with it. By 1890, the American people had collectively amassed more than $11 billion in personal debt.23

Not all Americans participated in reckless consumption to the same degree, but by the 1920s, the ethos of consumption and the goal of limitless production had solidified in American culture. Farmers on the Great Plains acted a lot like the greedy day-traders on the New York Stock Exchange or the real estate developers in Florida.24

ECONOMIC DOWNTURN [12:49-14:03]

And beneath the surface were warning signs that the economy was in trouble.

The auto industry began slowing its production as early as 1925. Likewise, residential construction began to slow. But, regardless, the stock market continued to grow at an astounding rate. Like in the Florida land boom, speculators poured money into the market, inflating the cost of stocks to such a degree that they no longer had any relation to a company’s real value, its product, or the dividends it provided investors.25

International markets also showed warning signs. After WWI, Germany owed the Allies $33 billion in reparations. Their economy tanked, and the nation could not pay its war debts to Britain or France. Then, those countries struggled to repay American banks the $10 billion dollars they had taken out in war loans.26

The world was in debt. Yet…prices on Wall Street soared.

MARKET CRASH [14:03-16:04]

Then, in the Fall of 1929, the market came crashing down. On October 23, investors began to sell their stock. As they sold, the prices for those stocks declined, setting off a frenzy to unload the stocks before their prices fell further, which only caused them to plummet. Six million stocks were sold that day—so many that the ticker which recorded prices ran two hours behind. By the day’s end, $4 billion had been wiped out.27

President Herbert Hoover tried to reassure the American people. “The fundamental business of the country, that is the production and distribution of commodities, is on a sound and prosperous basis.”28 Hoover was wrong, but we might forgive him his lack of foresight. No one knew how bad it would get.

On October 29th, 1929—a day which became known as “Black Tuesday”—nearly 16.5 million shares were sold, sending prices in a free-fall. Investors and the American people looked on in shock and horror as the plummet lasted another three weeks. By mid-November, $26 billion of wealth had disappeared, and that’s in 1929 dollars.29

For the next decade, the American people lived through the Great Depression.

CAUSES OF DEPRESSION [16:04-19:45]

Significant as it was, the Stock Market Crash did not cause the Great Depression. In fact, though estimates vary, only about 3% of Americans owned any stock at all. The market crash itself was a symptom of an unhealthy economy.30

Throughout the 1920s, banks were already on shaky ground. An average of 500 died each year. The Depression just made it worse.31

Some banks had taken people’s deposits and lost them in the stock market. Others struggled to stay afloat when customers couldn’t repay their loans.32

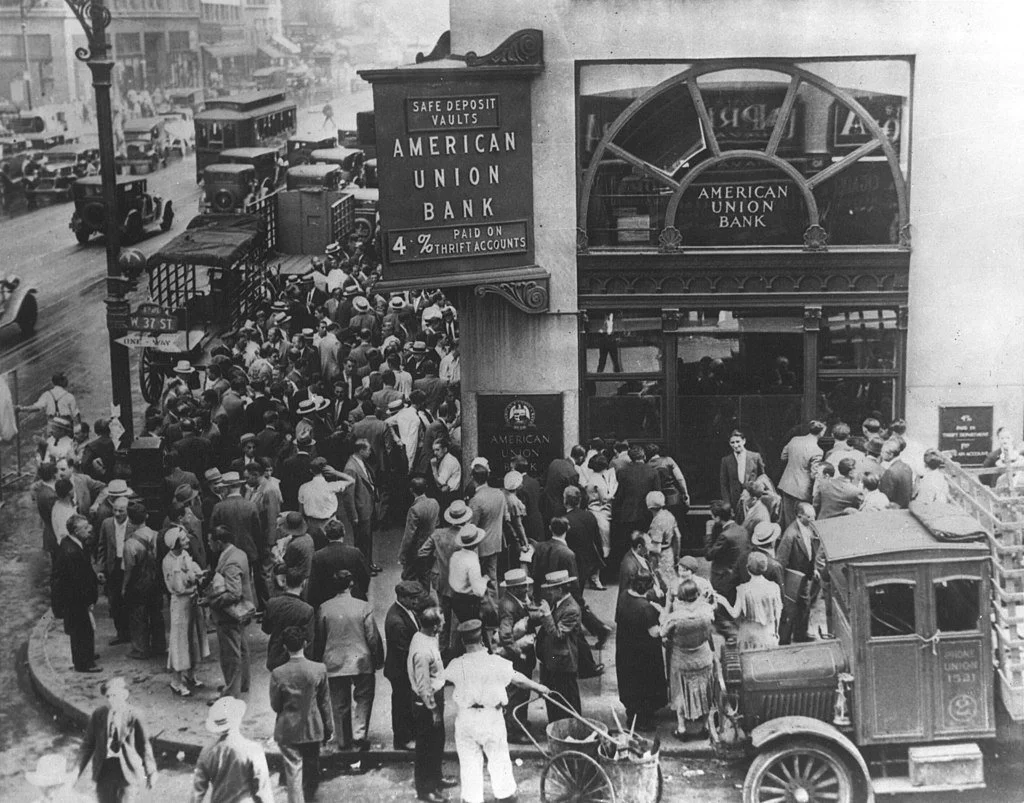

There was not yet any deposit insurance which meant that if a bank failed, a person’s money just disappeared. Poof. Their life savings gone—through no fault of their own. With so many banks failing, sometimes panic would set in. Fearful that a bank might fail, depositors would rush to withdraw their funds. It’s called a bank run. If a bank didn’t have the cash on hand to give everyone their funds at the same time, they would begin calling in their loans. If they couldn’t gather the cash in time, the bank died. Bank runs could wipe out even a healthy bank.

In 1930, the first full year of the Depression, 1352 banks died.33

Bank Run on American Union Bank, New York City, April 26, 1932. See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Inequality of wealth also contributed to the unhealthy economy. Though the economy had been growing, income rose unevenly. The middle class made gains, but the wealthy made more. Even in a booming industry like steel, profits soared but wages for workers remained stagnant. Overall, 30% of the Nation’s income went to just 5% of Americans.34

A stagnant middle class will, eventually, limit the economy. For example, the car was a major engine of economic expansion in the 1920s. But without a growing middle class, eventually everyone who could purchase a car already had one. And when demand decreased, the industry shrunk, and it sent ripples through other industries.35

Finally, some economists and historians argue that the Depression would not have lasted so long, had the US government not mismanaged the crisis.36

President Hoover believed the government should have minimal interference in the economy. But in 1930, he did sign the Smoot-Hawley Tariff, made famous by Ferris Bueller’s boring history teacher.

By raising taxes on goods imported to the US, it would protect farmers and manufacturers from international competition. It was a popular idea in the 1920s, but by the time Hoover signed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff, most farmers actually opposed it. Manufacturers likewise worried it would harm the economy. The critics were right. When Hoover signed the bill, international trade declined, likely prolonging the Depression.

THE GREAT DEPRESSION—GENERAL [19:45-20:57]

Overproduction, world debt, unregulated banking, inequality, and government mismanagement all contributed to the Great Depression. The problem was no one thing caused it. It was a systematic failure. Which made it incredibly difficult to solve. And the results were terrifying….

By the end of 1930, over 26,000 businesses had failed, and nearly 9% of the workforce was unemployed.37 By 1932, unemployment reached a shocking 23%. Unemployment numbers only scratch the surface, because they don’t capture families—the women, children, and the elderly—who depended on a worker to bring home a paycheck. At the Depression’s worst, around 30 million Americans were without an income.38

LIFE DURING THE DEPRESSION [20:57-25:34]

Families bore the brunt of the Depression. Marriage rates declined and by 1933, the birthrate had declined by 15% of the pre-Depression average. Americans at the time expected men to be the primary providers for their family. Without a job, many men struggled with self-worth. One unemployed man reflected, “I lost something. Maybe you can call it self-respect, but in losing it I also lost the respect of my children, and I am afraid that I am losing my wife.”39

Because of the prevailing idea of a male breadwinner, women were among the first to be laid off during the Depression. However, women workers also benefited from the gender division of labor. The auto and steel industries had overwhelmingly male workforces and suffered huge layoffs. Industries dominated by women, like education, experienced wage reductions but fewer layoffs overall.40

The African American community had its own unique struggles.

After WWI, many Southern Blacks had moved to Northern cities. It’s called The Great Migration. Broadly speaking, they had been in the cities for a shorter period and therefore had less time to develop careers before the Depression hit. When businesses shrunk, employers usually practiced a policy of “last hired, first fired.” Let the newest employees go first, rather than the workers who had been with the company for years or decades.41 It makes sense, but, of course, racial prejudice also influenced this policy.

In the urban centers of the North, overall unemployment reached as high as 25%. But in cities like Chicago, New York, and Pittsburgh, African American unemployment reached 50%. In Detroit and Philadelphia, it was even worse. There, 60% of African American workers were unemployed.42

Perhaps no one suffered more during the Depression than Black Americans.

Nearly everyone, however, struggled to find work, food, or shelter.

In a reversal of a decades-long population trend, Americans fled the cities. Some rode the rails, sneakily hopping on train cars and riding from town to town, looking for work.43

Others lived in shantytowns which sprung up on the outskirts of major cities across the country. Down on their luck Americans constructed shacks made of scrap wood, tarpaper, and cardboard. The people called them “Hoovervilles.”44

Hooverville on the Seattle tide flats, Seattle, Washington, 1933. Seattle Municipal Archives, CC by 2.0 Generic license, via Wikimedia Commons.

Charities distributed food to the hungry but were frankly overwhelmed. Lines wrapped around city blocks as men waited to receive bread, soup, or a cup of coffee.45

One of the most popular songs during the Great Depression was Bing Crosby’s “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?” The lyrics recounted the promise of America, written from the perspective of the men who had built it. But now the promise had crumbled, and the men were left with nothing.

They used to tell me I was building a dream,

And so I followed the mob,

When there was earth to plow, or guns to bear,

I was always there right on the job.

They used to tell me I was building a dream,

With peace and glory ahead,

Why should I be standing in line,

Just waiting for bread?

Once I built a railroad, I made it run,

Made it race against time.

Once I built a railroad; now it’s done.

Brother, can you spare a dime?

The song gave voice to what millions of Americans were feeling.

BONUS ARMY [25:34-27:39]

This brings us to the Bonus Army.

Back in 1924, Congress approved a special bonus payment to the veterans of WWI. They would receive a one-time payment either in 1945, or their family would receive it upon their death. In the thralls of the Depression, many veterans hoped the government would issue the payment early.

In June of 1932, Congress considered a bill to issue the bonus. To show their support, 20,000 former soldiers, dubbed the “Bonus Army,” descended on Washington D.C. The Secret Service infiltrated the group, worried the men might be communists. But they found very few radicals and concluded that the men were “Americans, down on their luck.”

Their protests failed, however, and Congress refused to grant the bonus early. Rather than leave Washington, thousands of men camped outside the city in their own Hooverville. In late July, the local police tried to expel them, and, in the ensuing riot, they shot two veterans dead.

The Bonus Army encampment in Washington, D.C., 1932. Signal Corps Photographer, National Archives and Records Administration, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

President Hoover then sent in Army Chief of Staff General Douglas MacArthur, who was intent to “break the back” of the Bonus Army.

A force of bayonet-bearing infantry, cavalry, and six tanks descended upon the veteran camp, fired tear gas, and then set the encampment on fire. The event horrified the public, many of whom were sympathetic to the veterans. The event shows the desperation of the American people.46 Neither they nor their government knew what to do.

LEGACY OF THE DEPRESSION [27:39-28:23]

It’s difficult to fully comprehend how traumatic the Great Depression was. With hindsight, we can see that it lasted a decade. But those who lived through it had no idea how long it would last, or how long they would fear losing their income, their home, or food.

In 1980, the writer Alfred Kazan looked back upon his childhood. He said, “no one who grew up in the Depression ever recovered from it.”47

DUST STORMS [28:23-33:40]

In the midst of the economic depression, farmers on the Plains, who were already in debt, facing foreclosure and falling crop prices, experienced yet another disaster—drought.

In the spring of 1930, a drought struck the Eastern states. By 1931, its center had shifted to the Great Plains where it lasted another ten years. Record high temperatures followed. In 1936 alone, 4500 people died from excessive heat.48

Droughts, even severe ones, are natural. They have occurred before and since. But this one was different.

As we discussed earlier, farmers on the Great Plains were hell-bent on maximizing yields which not only led to the overproduction of crops but also destroyed the topsoil. They had farmed too much with equipment too powerful.

The sun baked the ground, evaporating any moisture it held. Without natural plants and grasses to hold it together, the dirt cracked and turned to dust. Then, the winds came and literally blew the earth away. Dust storms swept over the Plains.

On the Southern Plains—Texas, Oklahoma, Nebraska, Colorado—storms became so common that the region became known as the Dust Bowl. The cause of the Dust Bowl was unrestrained capitalism and what one historian described as “an absence of environmental realism.”49

The worst of them were called “black blizzards,” where waves of dust reaching 8000 feet high blocked out the noonday sun. They swallowed whole towns, derailed trains, and closed schools and businesses. Animals in the fields often choked to death. The people took refuge indoors, but that proved only a little better. Dust leaked through the windows and doors; covered food, beds, dishes, and the people themselves.50

With each storm, hospital admissions would surge. The American Red Cross set up emergency hospitals across the region.51

“People were scared,” recalled one farmer, “They were trying to figure out what was behind it. Some saw the end of the world, some the judgment of God in the storm.”52

On May 9th, 1934, a storm formed over Montana and Wyoming. It gathered dust as it moved over the Dakotas and then the Midwest, its winds reaching 100 mph. On May 11th, it reached the East Coast and blanketed Boston, New York, Washington D.C., and Atlanta. Over the following days, sailors in the Atlantic, some 300 miles from the coast, reported dust on the decks of their ships.53

1935 was the darkest year of the Dust Bowl era. In March alone, 5 million acres of wheat were destroyed by the storms.54

April 14th of that year became known as “Black Sunday.” The day began clear and warm. The people went about their work, went to town, attended church. But in the afternoon the weather suddenly changed. It dropped perhaps 50 degrees in only a few hours. Then, witnesses noticed ominous flocks of birds flying south, fleeing something yet unseen. Suddenly, in the north appeared a black blizzard—a wall of black dust headed their way.55

Dust storm approaching Stratford, Texas on Black Sunday, April 14, 1935. George Everett Marsh Jr., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

One family driving in their car realized they could not reach home. They pulled their car over and found shelter in an old building along the road. Inside, they found ten others also seeking shelter from the storm. They sat there together for over four hours, unable to even see their companions’ faces.56

One woman tried to reach home in her car, but the static electricity from the storm shorted out the ignition. Unable to see where she was going, she accidentally wandered into a field. Her husband arrived in his own truck just in time. He found her just as she was about to collapse, blind and struggling to breathe.57

“This is ultimate darkness,” remarked one newspaper, “so must come the end of the world.”58

OKIES [33:40-35:47]

Unsurprisingly, the Dust Bowl led many people to flee the region. Two hundred twenty-seven thousand left Kansas. Thousands more left Texas and Colorado. As many as 440,000 fled Oklahoma alone. Accordingly, they were all called “Okies.”59

Families packed all they could into a car or truck and left the rest. Most of them fled westward. On their journey, they camped along the roadside, finding shade under billboards or in camps of fellow vagabonds.

Their stories were captured in John Steinbeck’s captivating and incredibly depressing novel, The Grapes of Wrath.

Their forefathers had arrived on the Great Plains as pioneers, seeking land and the American Dream. In the 1930s, they fled the region as refugees.60

Photograph of Florence Owens Thompson, 32 year-old mother of seven and the subject of multiple images taken by Dorothea Lange at a pea-pickers camp in Nipomo, California, 1936. Dorothea Lange, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Okies escaped the dust, but not the Depression. Those who arrived in California hoped to find seasonal agricultural work, but they rarely received a warm welcome. In Los Angeles, the police formed a blockade to keep them out. They called it the “bum blockade.”61

Elsewhere in the state, Okies traveled from farm to farm, picking oranges, peaches, lemons, etc. With more workers than available jobs, Okies had little choice but to accept whatever pay was offered. If they were lucky, they’d work about six months and earn around $400.62

Depression and Bonus Army, Dust Bowl and Okies—what was America to do?

ROOSEVELT ELECTED [35:47-37:29]

President Hoover did not cause the Great Depression. There was no single cause of the Depression. But he was president during its first four years and had virtually no chance of winning reelection.

In 1932, his opponent was Democrat Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Roosevelt scored a crushing victory. He won 57% of the national vote and carried all but 6 states.63

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 1933. Elias Goldensky, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Since the Civil War, Republicans had dominated the federal government. Only two Democrats won the presidency between 1860 and 1932. But a new coalition of voters formed in the 1932 election, bringing together farmers from the South and West, urban industrial workers from the North, immigrants, and African Americans. This coalition made the Democrats the dominant party for the next 50 years.64

Furthermore, when it was founded, the Democratic Party favored states’ rights and opposed much federal intervention. During the Industrial Revolution, however, the party evolved and became more critical of big business. By 1932, the party had fully switched its philosophy and embraced a large and active federal government.65

The point we’re making is that the Great Depression reshaped American politics.

THE NEW DEAL [37:29-41:19]

Roosevelt campaigned that the American people needed a “new deal.” And that’s the name we give his reforms. Once in office, he created a flurry of new agencies, signed legislation in rapid fire, and sought to weaken the Depression’s grip on the country.

Several New Deal agencies were created with the specific intent of strengthening the urban economy.66

Roosevelt and Congress created the Securities and Exchange Commission (the SEC) to regulate Wall Street.67

He initiated a four-day mandatory holiday for every bank in the Nation in March of 1933. By giving them time to review their books, Roosevelt hoped to improve public trust in banks.68

To address both Wall Street and banking, Roosevelt signed the Banking Act of 1933, also called the Glass-Steagall Act. This act was a cornerstone of the New Deal. It separated commercial from investment banking, preventing banks from using someone’s deposits to invest in the stock market. It also created federal deposit insurance. If a bank died, the depositors’ savings would now be guaranteed by the government. Along with the banking holiday, these policies decreased bank runs.69

In 1934, Congress created the Federal Housing Administration, which insured mortgages and established the standard 30-year mortgage that allowed Americans to purchase homes with a lower downpayment. The Homeowners Loan Corporation of 1933 created standard methods for appraising homes and helped refinance home loans. These policies attempted to stabilize the housing market.70

Roosevelt’s administration also created agencies to directly employ Americans.

The Public Works Administration constructed roads, schools, and courthouses across the Nation. In New York, they built LaGuardia Airport and the Lincoln Tunnel. In the Florida Keys, they constructed the Overseas Highway.71

The Works Progress Administration (or WPA) was even larger, employing a total of 8.5 million people during its lifespan. They constructed 500,000 miles of highways and 8000 parks. Within the WPA was the Federal Art Project, which hired visual artists to teach in schools and commissioned murals in public buildings. The Federal Music Project hired musicians for symphonies or free public concerts. The Federal Theater Project produced everything from Shakespeare plays to marionette shows. The Federal Writers Project hired writers to interview former slaves and capture their stories. Their work is in the public domain and is a treasure trove for historians.72

And Roosevelt wasn’t done. Americans in the countryside also sought help from the government. “Please do something,” wrote one woman to the president.73 So, other parts of the New Deal targeted rural poverty.

RURAL REFORM [41:19-46:11]

While farmers on the Plains suffered from dust storms and drought, farmers elsewhere still overproduced crops and drove prices downwards. The Agricultural Adjustment Administration (or AAA), created in May of 1933, was tasked with solving this problem.

Under the AAA, farmers on the Great Plains were paid to decrease the acreage they farmed by 15%.74 The administration even paid farmers to dig up the cotton they had already planted. Afterwards, the administration set quotas for cotton production and taxed those who exceeded it. Facing a similar problem of excess pork, the AAA slaughtered millions of pigs.75

If it seems strange to destroy cotton and meat while Americans struggled to clothe and feed themselves, you’re right. But these policies sought to address longstanding problems of supply and demand. Rather than provide immediate relief, they addressed problems created by industrial farming a half century prior.

However, in 1936 the Supreme Court ruled that the AAA was unconstitutional. Its funding came from a tax on food processors which is not okay, I guess. Honestly, I don’t really understand it. Afterwards, Roosevelt signed the Soil Conservation and Domestic Allotment Act, which also paid farmers not to farm, but the funding came out of the general government revenues, which, I have read, is constitutional. Again, I don’t really understand it.76

Anyway, other policies addressed the land itself.

Roosevelt created the Soil Conservation Service in 1935. The purpose was to address the soil erosion which had led to the Dust Bowl. The service funded scientific research on erosion and created drainage projects to prevent flooding.77

The government also began a program to pay farmers 20 cents an acre to dig furrows in the fields across the Great Plains. This would slow soil erosion and make it more resistant to the harsh winds. From July 1936 to July 1937, farmers on the Plains dug furrows across 8 million acres.78

The Tennessee Valley Authority Act of 1933 created an agency to oversee the development of the Tennessee River, which included building dams to control flooding, fighting soil erosion and deforestation, and constructing hydro-electric power stations. It was ambitious and a success. It brought electricity to Americans who had no prior access.79

Map of the Tennessee Valley Authority, circa 1942. National Archives and Records Administration, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Roosevelt then took the same approach to the national level. He created the Rural Electrification Commission in 1935, which offered loans to build generating plants and construct power lines and help bring electricity to rural areas across the country. When the Commission began, only 20% of farms had access to electricity. Ten years later, 90% had power.80

If you’re tired, too bad, because the reforms didn’t stop there. In 1934, Congress granted $525 million for drought relief and hired farmers for manual labor, like building reservoirs.81 The Farm Credit Act addressed foreclosures of farms. Twenty percent of all farmers in the country refinanced their mortgages under the act.82 The Farm Security Administration educated farmers on more effective methods of farming. In 1937, 8000 farmers participated in the program.83

Agricultural aid became the single largest expense in the federal budget, costing $1.4 billion a year.84

We are just scratching the surface. If we covered every New Deal Agency, this episode would be 19 hours long, minimum.

EVALUATION OF THE NEW DEAL [46:11-49:35]

What do we make of all of this?

Did the New Deal end the Great Depression? No. Did it bring back the rain? Also, no. The New Deal was far from perfect. It helped stop the bleeding, but it did not end the Depression. It was created ad hoc in an emergency, and it reflects those conditions. This makes its legacy difficult to evaluate.

The economy began to recover during Roosevelt’s first term, and he was reelected in a landslide—he won all but two states. But things turned sour again during his second term. In an attempt to balance the budget, the administration cut back government spending, which decreased the public’s purchasing power. A recession within the Great Depression began in ‘37 and lasted into ‘38. During the “Roosevelt Recession” nearly 4 million people lost their jobs.85

However, New Deal reforms were not simply about economic recovery. Judging them by that standard would be missing the point. Many reforms were intended to create long-term stability. By that standard, the New Deal looks much better. The 25 years after WWII were the most prosperous in American history, thanks in part to the stability the New Deal created in the stock market, banking, and housing.

But any evaluation of the New Deal goes beyond debates about economic policy. The conditions of the ‘30s inspired a deeper reconsideration of the proper role and responsibility of government.

Herbert Hoover remained a critic of Roosevelt and the New Deal. He claimed that the policies were “European”, and they would lead to “the crippling and possibly the destruction of the freedom of men.” Men would become slaves to a powerful government.86

Roosevelt defended the New Deal against such criticism, saying, “In our efforts for recovery, we have avoided on the one hand the theory that business should and must be taken over into an all-embracing Government. We have avoided on the other hand the equally untenable theory that it is an interference with liberty to offer reasonable help when private enterprise is in need of help.”87

The proper size and function of the American government is a debate as old as the Union itself. But in its modern form, the debate was shaped by the Depression and the Dust Bowl. As a country, we are still arguing over the legacy of these disasters.

WORLD WAR II [49:35-52:44]

To truly end the Depression, the Nation needed something colossal. One author summarized it well, “What made the Depression so appalling a human tragedy was that it could be overcome only by an event as awesome, as terrifying, and as irresistible as the Depression itself. And that was the Second World War.”88

During the Depression, much of the manufacturing capacity of the country lay dormant—unemployed workers, empty factories, machines gathering dust. But then America entered the Second World War in 1941, and the demands of war brought American manufacturing back to life.89 The war allowed the government to pour money into the economy without the criticism that such action was un-American.

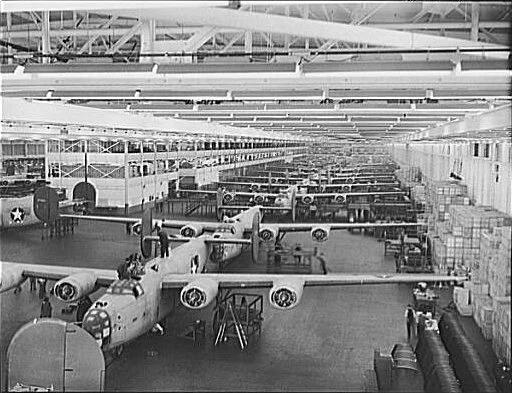

Within six months the government awarded $100 billion dollars in contracts to private businesses. Henry Ford turned to airplane production. His factory outside of Detroit employed more than 40,000 workers. By 1944, those workers produced a new B-24 bomber every sixty-three minutes.90

B-24E (Liberator) bombers being made at Ford’s Willow Run plant, circa 1942. Howard R. Hollem, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Businessman Henry Kaiser used government contracts to build shipyards along the West Coast. His shipyard in Richmond, CA employed 90,000 people. Among them were the refugees of the Dust Bowl who had fled west during the Depression.91

By the conclusion of the war, American factories had produced 40 billion bullets, 6.5 million rifles, 2.3 million trucks, over 630,000 jeeps, and nearly 300,000 airplanes.92

That was just military production, soldiers also needed to be clothed. The Army placed orders for 500 million pairs of socks, 250 million pairs of pants, and 250 million pairs of underwear.93

And who was wearing all that underwear? The 10 million men drafted into military service. Demand went up, the labor force shrunk, and suddenly there were jobs.94 By the end of 1943, Congress abolished New Deal agencies like the Works Progress Administration—they were no longer needed. Finally, in 1943, unemployment dropped below its 1929 level. One shipyard worker from Virginia remarked, “After all the hardships of the Depression, the War completely turn my life around.”95

DUST BOWL ENDS [52:44-54:51]

After a decade of drought, the rains finally returned in the ‘40s. By 1941, the land came back to life. With newly learned water saving techniques and government oversight, the Plains again produced an abundance. The crop yield of 1942 was the largest since 1931.

The war, too, revived the farms. Congress passed the Tydings Amendment in 1943, which declared that agricultural workers were exempt from the draft—their work was too important. During the war, nearly 2 million farmers stayed in the fields to feed the Nation and its soldiers.96

In fact, farmers returned to the Plains, once again seeking their fortune in the wheat harvest. Where before overproduction had led to plummeting prices, the war increased demand. In 1945, farmers harvested 2.5 million acres of wheat.97

Laura Briggs was about eleven years old when the US entered the war. After years of living in poverty, her family moved from their farm in Idaho to California to work in a defense plant. However, they ended up returning to the farm. As prices improved, so did their standard of living. They got electricity and indoor plumbing. And, because the farmer fed the soldier, they got respect. “Where before we were looked down upon, now we were important,” Briggs reflected.98

The economic and environmental disasters had finally subsided, thanks in part to another, even more deadly disaster—a world war.

CONCLUSION [54:51-56:40]

We’ve told the stories of two disasters: the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl. But, in many ways, they are the same story. They are the consequences of a blind belief in progress and a desire to maximize profits above all else. Americans don’t like being told they have limits. Central to the capitalistic view is theoretical limitless growth and continued production.99

Develop more real estate, buy more stocks, produce more goods, farm more land. More, more, more. This impulse can inflate prices until a bubble bursts and the market collapses, and it can literally destroy the ground.

It’s a frightening story of an economic disaster, compounded by an environmental one, bookended by the two bloodiest wars in human history.

Thanks for listening.

[American History Remix is written and produced by Will Schneider and Lyndsay Smith. For the latest updates, be sure to follow us on Instagram and Threads. Check out our website for episode transcripts, recommended reading, and resources for teachers. That’s AmericanHistoryRemix.com.]

REFERENCES

Barnes, Jay. Florida’s Hurricane History. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998.

Dickstein, Morris. Dancing in the Dark: A Cultural History of the Great Depression. New York: W.W. Norton, 2010.

Dumenil, Lynn. The Modern Temper: American Culture and Society in the 1920s. New York: Hill and Wang, 1995.

Edwards, Rebecca. New Spirits: Americans in the Gilded Age: 1865-1905. Oxford University Press, 2010.

Gerdes, Louise I., ed. The Great Depression: Great Speeches in History. San Diego, CA: Greenhaven Press, Inc., 2002.

Gromley, Ken, ed. The Presidents and the Constitution: A Living History. New York: New York University Press, 2016.

Harris, Mark Jonathan, Franklin D. Mitchell, and Steven J. Schechter, eds. The Homefront: America during World War II. New York: Putnam, 1984.

Hoover, Herbert. Addresses Upon the American Road by Herbert Hoover, 1933-1938. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1938.

Howe, David Walker. What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Kennedy, David M. Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Klein, Maury. Rainbow’s End: The Crash of 1929. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Leach, William. Land of Desire: Merchants, Power, and the Rise of a New American Culture. New York: Vintage Books, 1994.

Maisel, L. Sandy. American Political Parties and Elections: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Mulvey, Deb ed. 'We Had Everything But Money.' Greendale, WI: Roy Reiman, 1992.

Nardo, Don, ed. The Great Depression. San Diego, CA: Greenhaven Press, Inc., 2000.

Polenberg, Richard. The Era of Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1933-1945: A Brief History with Documents. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2000.

Rauchway, Eric. The Great Depression and the New Deal: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Sundquist, James L. Dynamics of the Party System: Alignment and Realignment of Political Parties in the United States. Washington, D.C: The Brookings Institution, 1983.

White, Eugene N. 2009. “Lessons from the Great American Real Estate Boom and Bust of the 1920s.” NBER Working Paper Series. National Bureau of Economic Research, December. http://www.nber.org/papers/w15573.

Worster, Donald. Dust Bowl: The Southern Plains in the 1930s. 25th anniversary ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

NOTES

1 Lynn Dumenil, The Modern Temper: American Culture and Society in the 1920s (New York: Hill and Wang, 1995), 303-304.

2 Jay Barnes, Florida’s Hurricane History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 112-13, 120-21, 126. “Devastation in Miami from the 1926 Hurricane,” Library of Congress, accessed December 28, 2023, https://www.loc.gov/item/2021670726.

3 Eugene N. White, 2009, “Lessons from the Great American Real Estate Boom and Bust of the 1920s,” NBER Working Paper Series, National Bureau of Economic Research (December), 44, http://www.nber.org/papers/w15573.

4 Maury Klein, Rainbow’s End: The Crash of 1929 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 23.

5 Donald Worster, Dust Bowl: The Southern Plains in the 1930s, 25th anniversary ed., (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 89.

6 Worster, Dust Bowl, 90-92.

7 Worster, Dust Bowl, 89-90.

8 Worster, Dust Bowl, 183.

9 Worster, Dust Bowl, 92-93.

10 Klein, Rainbow’s End, 24-25.

11 Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 59.

12 David M. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 22. Eric Rauchway, The Great Depression and the New Deal: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 13.

13 Rauchway, The Great Depression and the New Deal, 13. Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 59.

14 Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 76-77.

15 Rauchway, The Great Depression and the New Deal, 13.

16 Worster, Dust Bowl, 182.

17 “Wheat Data,” Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, last modified December 11, 2023, https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/wheat-data/.

18 The Hutchinson News, July 25, 1929, 1. The Dodge City Journal, Aug 29, 1929, 1.

19 Worster, Dust Bowl, 92-94.

20 Worster, Dust Bowl, 182-84.

21 Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 33-34, 44. Worster, Dust Bowl, 94-97.

22 William Leach, Land of Desire: Merchants, Power, and the Rise of a New American Culture (New York: Vintage Books, 1994), 16.

23 Rebecca Edwards, New Spirits: Americans in the Gilded Age: 1865-1905 (Oxford University Press, 2010), 94.

24 Worster, Dust Bowl, 80, 94-97.

25 Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 34-35.

26 Kennedy, Freedom From Fear, 72-73.

27 Kennedy, Freedom From Fear, 37.

28 Rauchway, The Great Depression and the New Deal, 25.

29 Kennedy, Freedom From Fear, 38; Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 305.

30 Kennedy, Freedom From Fear, 41

31 Kennedy, Freedom From Fear, 65.

32 Rauchway, The Great Depression and the New Deal, 30.

33 Kennedy, Freedom From Fear, 65.

34 Klein, Rainbow’s End, 84-85. Edward R. Ellis, “A Nation in Torment,” in The Great Depression, ed. Don Nardo (San Diego, CA: Greenhaven Press, Inc., 2000), 41. Dumenil, The Modern Temper, 306.

35 Rauchway, The Great Depression and the New Deal, 14.

36 Louise I. Gerdes, ed., The Great Depression: Great Speeches in History (San Diego, CA: Greenhaven Press, Inc., 2002), 14.

37 Kennedy, Freedom From Fear, 58-59.

38 Rauchway, The Great Depression and the New Deal, 33, 40.

39 Kennedy, Freedom From Fear, 165.

40 Kennedy, Freedom From Fear, 164.

41 Rauchway, The Great Depression and the New Deal, 46.

42 Mary-Elizabeth B. Murphy, "African Americans in the Great Depression and New Deal," Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History, November 19, 2020, https://oxfordre.com/americanhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.001.0001/acrefore-9780199329175-e-632.

43 Rauchway, The Great Depression and the New Deal, 46. Raphael Magelky, “Days of Riding the Rails Remembered,” in ‘We Had Everything But Money,’ ed. Deb Mulvey (Greendale, WI: Roy Reiman, 1992), 21.

44 Rauchway, The Great Depression and the New Deal, 44. Kennedy, Freedom From Fear, 91.

45 Cecile Culp, “Depression Hit Us Like a Tornado,” in ‘We Had Everything But Money,’ 14-15.

46 Rauchway, The Great Depression and New Deal, 50-52. Kennedy, Freedom From Fear, 92.

47 Morris Dickstein, Dancing in the Dark: A Cultural History of the Great Depression (New York: W.W. Norton, 2010), xv.

48 Worster, Dust Bowl, 10-12.

49 Worster, Dust Bowl, 28, 42-43.

50 Worster, Dust Bowl, 15-16.

51 Worster, Dust Bowl, 20-22.

52 Bill and Ocie Christian, “We Were There When the Dust Bowl Days Started,” in ‘We Had Everything But Money,’ 39.

53 Worster, Dust Bowl, 13-14.

54 Worster, Dust Bowl, 16-18.

55 Worster, Dust Bowl, 18.

56 Worster, Dust Bowl, 18.

57 Worster, Dust Bowl, 19-20.

58 Worster, Dust Bowl, 17.

59 Worster, Dust Bowl, 48. Kennedy, Freedom From Fear, 195.

60 Kennedy, Freedom From Fear, 195.

61 Worster, Dust Bowl, 52.

62 Worster, Dust Bowl, 52-53.

63 William D. Pederson, “Franklin Delano Roosevelt,” in The Presidents and the Constitution: A Living History, ed. Ken Gromley (New York: New York University Press, 2016), 411.

64 L. Sandy Maisel, American Political Parties and Elections: A Very Short Introduction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 38.

65 Kennedy, Freedom From Fear, 125-28. James L. Sundquist, Dynamics of the Party System: Alignment and Realignment of Political Parties in the United States (Washington, D.C: The Brookings Institution, 1983), 198-99.

66 John F. Bauman and Thomas H. Coode, “In the Eye of the Great Depression,” in The Great Depression, ed. Don Nardo (San Diego, CA: Greenhaven Press, Inc., 2000), 53.

67 Rauchway, The Great Depression and the New Deal, 62.

68 Kennedy, Freedom From Fear, 135-37.

69 Rauchway, The Great Depression and the New Deal, 59.

70 Kennedy, Freedom From Fear, 369-70.

71 Kennedy, Freedom From Fear, 252.

72 Kennedy, Freedom From Fear, 252-56. Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers' Project, 1936 to 1938, Library of Congress, accessed October 7, 2024, https://www.loc.gov/collections/slave-narratives-from-the-federal-writers-project-1936-to-1938/about-this-collection/.

73 Worster, Dust Bowl, 38.

74 Worster, Dust Bowl, 156.

75 Rauchway, The Great Depression and the New Deal, 78-80.

76 Worster, Dust Bowl, 157.

77 “Soil Conservation Service,” Living New Deal, accessed December 23, 2023, https://livingnewdeal.org/glossary/soil-conservation-service-scs-1935/.

78 Worster, Dust Bowl, 40-41.

79 Kennedy, Freedom From Fear, 148.

80 Rauchway, The Great Depression and the New Deal, 91-92. Kennedy, Freedom From Fear, 252.

81 Worster, Dust Bowl, 39-40.

82 William E. Leuchtenburg, “Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, 1932-1940,’” in The Great Depression, ed. Don Nardo (San Diego, CA: Greenhaven Press, Inc., 2000), 121.

83 Worster, Dust Bowl, 161.

84 Worster, Dust Bowl, 154-55.

85 Richard Polenberg, The Era of Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1933-1945: A Brief History with Documents (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2000), 15, 21.

86 Herbert Hoover, Addresses Upon the American Road by Herbert Hoover, 1933-1938 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1938), 173-74.

87 “FDR’s Statements on Social Security,” Social Security Administration, accessed October 4, 2024, https://www.ssa.gov/history/fdrstmts.html.

88 Louise I. Gerdes, ed., The Great Depression: Great Speeches in History (San Diego, CA: Greenhaven Press, Inc., 2002), 14.

89 Kennedy, Freedom From Fear, 617.

90 Kennedy, Freedom From Fear, 626, 653-54.

91 Kennedy, Freedom From Fear, 651. “Capturing Unity: Building Warships in Richmond,” Dorothea Lange Digital Archive, Oakland Museum of California, accessed October 4, 2024, https://dorothealange.museumca.org/section/capturing-unity-building-warships-in-richmond/.

92 Kennedy, Freedom From Fear, 655.

93 Kennedy, Freedom From Fear, 627.

94 Steven Horwitz and Michael J. McPhillips, “The Reality of the Wartime Economy: More Historical Evidence on Whether World War II Ended the Great Depression,” The Independent Review 17, no. 3 (2013), 329. Though these authors argue that this process did little to affect most Americans’ standard of living.

95 Rauchway, The Great Depression and the New Deal, 126-27. Quote from Kennedy, Freedom From Fear, 644.

96 Kennedy, Freedom From Fear, 634, 646.

97 As a result of heightened demand during the war, Southern Plains farmers had increased the acreage devoted to wheat by 2.5 million acres by 1945, much of that land having been reclaimed in response to the droughts through federally funded programs. Worster, Dust Bowl, 225.

98 Mark Jonathan Harris, Franklin D. Mitchell, and Steven J. Schechter, eds, The Homefront: America during World War II (New York: Putnam, 1984), 32-35, 163-65. Quote from p. 163.

99 Worster, Dust Bowl, 189.