VOL. 3 EPISODE 8: THE ROAD TO WORLD WAR II

The shadow of the First World War hung over the world. The victors were exhausted and the vanquished wanted revenge. We discuss the death of European democracies, the global origins of World War II, and America’s reluctant journey to war.

INTRODUCTION [0:00-02:41]

On November 11th, 1935, George Earle, the governor of Pennsylvania, gave a speech to a crowd in celebration of Armistice Day, the day that commemorates the end of the First World War.

The war’s conclusion in 1918 had brought neither peace nor stability. Since then, both Italy and Germany had sunk into dictatorships, and within a few months of the Governor’s speech, a civil war would begin in Spain.

To Governor Earle, the lesson was clear. “Let us turn our eyes inward,” he declared, “If the world is to become a wilderness of waste, hatred, and bitterness, let us all the more earnestly protect and preserve our own oasis of liberty.”1 The governor spoke for many Americans at the time who desperately wanted the US to remain unentangled in world events.

For most of its history, the United States was concerned only with its own continent, not global affairs.

At the turn of the 19th century, however, America broke with its history and claimed a small Pacific empire and even joined World War I. But in the decades that followed, the country again retreated into itself.

As fascism spread across Europe and Japan conquered the Pacific, most Americans were committed to keeping the country isolated. Even in 1939, when World War II began, America did not rush to join. Over two full years lapsed before the Nation finally threw off its isolationism and entered the war.

Today we’re going to place America in its global context. We’ll explore the origins of the Second World War, and the long road towards America’s entry into it.

Let’s dig in.

—Intro Music—

[Welcome to American History Remix, the podcast about the overlooked and underexplored parts of American history. We’re glad you’re here!]

WORLD WAR I [02:41-07:04]

The roots of World War II are in World War I. Hailed as “The Great War” and the “war to end all wars,” the conflict was staggering.

It began in 1914 and lasted until 1918. Europe divided itself into two great alliances. The Central Powers consisted of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire. While France, Great Britain, Russia, and Italy made up the Allies.2

Europe during World War I. Department of History, United States Military Academy, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

It was the world’s first industrial war. Both sides fought with machine guns, hand grenades, flame throwers, airplanes, tanks, and poisoned gas. In the end, the “Great War” sent ten million men to their graves.3

America remained neutral for most of the conflict but was eventually drawn in. US banks had made wartime loans to both Britain and France. Then, in 1915, Germans sank the British ship the Lusitania off the coast of Ireland. 1200 people were killed, including 128 US citizens.4

Finally, in 1917, Germany, fearful that America would enter the war against them, secretly encouraged Mexico to attack the US. If it did, Germany offered to help Mexico regain land in the American Southwest. This offer was called the Zimmerman Telegram. It was intercepted, made public, and it outraged the American people. In April 1917, American President Woodrow Wilson asked Congress for a Declaration of War. America entered the war at the eleventh hour and tipped the scales for the Allies.5

When the war concluded, President Wilson issued his Fourteen Points—his vision for a post-war world. He wanted arms limitations, freedom of the seas, he called for an end to secret treaties between nations, and he called for self-determination in colonial territories. His most ambitious plan was for a League of Nations—an international body where representatives of the nations could settle disputes without armed conflict.6

It was a noble but perhaps naive dream.

Leaders of the victorious countries converged in Paris in 1919 to settle the terms of the war. Britain and France, angry after four years of bloody warfare, wanted vengeance and to grow their empires. Their leaders cared little for Wilson’s vision. Wilson, too, was unprepared for diplomatic negotiations. Defeated Germany was left out of negotiations the entirely and simply had to sit there and let the other nations determine its fate.7

The final document—the Treaty of Versailles—was signed on June 28th, 1919. The terms crippled Germany. Though it had not started the war, it was forced to accept full blame and pay $33 billion in reparations to the Allies. At the same time, it also lost valuable economic resources. It lost its international colonies, and some of its most important industrial territory was ceded to France. One historian wrote that Germany had to bear the “economic burden of a vengeful peace.”8

US RETURNS TO ISOLATIONISM [07:04-09:15]

The carnage of World War I shook the American people. Many were left disillusioned. In one brief year of fighting, 116,000 American soldiers died.9

Americans came to regret their participation in the war. They later called it “the European war.” In 1935, Senator Homer T. Bone reflected “the Great War was utter social insanity, and was a crazy war, and we had no business in it at all.” The senator was not alone. By 1937, 70% of Americans believed joining World War I had been a mistake.10

Those who now favored isolationism were a diverse group, spread across political parties and geographic regions. They believed that the problems in Europe and Asia were not a threat to the US. European nations were stuck in an endless struggle for power and empire. But who cares? The US broke free of that struggle with its independence, right? So, leave Europe alone.11

One historian described the post-war sentiment as a “hostility towards the outside world.” America refused to even join the League of Nations, even though their president had proposed it. Then, in 1921 and ‘24, it instituted severely restrictive immigration quotas. In 1935, Texan representative Maury Maverick declared, “We don’t like foreigners anymore.”12

ITALY & THE RISE OF MUSSOLINI [09:15-11:19]

Other nations felt the aftershock of the war even more severely. Italy’s government, which was a constitutional monarchy, struggled to maintain order. Many Italians were bitter that their country did not receive more territory under the Treaty of Versailles.13

Meanwhile, soldiers returned from the war and swelled the number of the unemployed. Poor farmers began squatting on the land of the wealthy, and competing political parties fought for power.

In 1919, Benito Mussolini founded a new political party, the National Fascist Party—a rightwing, authoritarian party.14

It was the wealthy Italian landowners who helped bring the Fascists to power. The liberal government wanted to tax the wealthy and to recognize the land grabs of the poor. Outraged, the wealthy provided funds for bands of fascists to attack communists and socialists. In 1921, Mussolini and other party leaders were elected to Parliament, giving credibility to the extremists. Bands of fascists wreaked havoc across the country, attacking political institutions. Mussolini, titling himself “the Duce” or leader. He claimed he stood for law and order and blamed communists and socialists for the violence his men caused.15

Then, in October 1922, Mussolini marched on Rome and pressured Italian King Victor Emmanuel III to appoint him as prime minister. And the king did.16 The Fascists were now in control.

THE PHILOSOPHY OF FASCISM [11:19-13:30]

Fascism was not a coherent political philosophy. It was about political control—power through violence. But it did promise Italians two things. First, greatness. Italy would become a mighty militaristic state.

Second, order. Mussolini transformed Italy into a one-party, authoritarian state. Even as he revoked civil liberties, he developed a cult-like following. His subordinates learned to never question him. “My own animal instincts are always right,” he claimed.17

To understand Mussolini’s rise, we need to understand nationalism. Nationalism can be a tricky word to define. Think of it as rampant, unhealthy patriotism. The idea is that a nation has one unified culture and identity, with ethnic, religious, or racial unity among the people. In that unified society, the people believe they are superior to other nations because of their ethnicity, religion, race, or whatever. The interests of their nation come above all else, and the goals are often militaristic. The people desire to see the nation grow in power and prestige.

The American people remained aloof to the events in Italy. Or, perhaps, they offered a little admiration. Time Magazine featured Mussolini on its cover in August of 1923. The US ambassador regarded Mussolini’s rise as “a fine young revolution.”18

Benito Mussolini on Time cover 1923. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

GERMANY’S DEFEAT [13:30-15:29]

Nowhere did the shadow of World War I hang heavier than in Germany.

With Allied victories stacking-up in the summer of 1918, German leaders saw that defeat was imminent. Rather than let the Allies ravage the German heartland, the military leaders sued for peace. The German people were shocked and didn’t understand why the military agreed to an armistice while the army was still intact.19

In the fall of 1918, a young Adolf Hitler, serving as a private in the Imperial German Army, was recovering from wounds in a military hospital when news of the surrender reached him. “So it had all been in vain,” he reflected. “The war, the hunger, the death, it had amounted to nothing.”

To the Germans, surrender felt like betrayal. Unable to understand how it could happen, they looked for a conspiracy. Someone to blame. A common myth was that Jews and Communists were somehow responsible. The consequences of this conspiracy were devastating.

As Hitler lay in his hospital bed grappling with defeat, he had a realization. “I became conscious of my own fate,” he later wrote, “I resolved to become a politician.”20

THE NAZI PARTY [15:29-18:00]

Prior to the First World War, Germany had been a constitutional monarchy. After the war, it formed a new government called the Weimar Republic. A president was directly elected by the people. Among his powers was to appoint a chancellor to be the leader of the Reichstag, the legislative body.21

In 1919, Hitler joined a newly formed political party, the German Workers Party, that attracted disillusioned soldiers like himself. It was renamed the German Nationalist Socialist Workers Party, or the “Nazi” Party in 1920, and Hitler was its unquestioned leader by 1921.22

Adolf Hitler as he appeared on his government issued card allowing him to carry weapons, 1921. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The Nazi Party was another far-right political party. It sought to overthrow the Weimar Republic, which it saw as weak, and replace it with a new German state that would unite all ethnic Germans together. This was, again, the idea of nationalism. The superiority of those from Northern Europe, the supposed Aryan race, was unquestioned. The nation would purge itself of all foreigners, especially Jews, and those it considered weak—criminals and the mentally ill. German men would be physically fit and disciplined. German women would bear healthy German children.

With a revitalized and robust German populous, the nation would launch a war for Lebensraum, the German word for “living space.” The nation needed land and resources to sustain itself.

The ultimate goal was to redeem the nation after its defeat in the First World War—to shake off the humiliation of the Treaty of Versailles and restore German power and prestige. The Nazis promised to make Germany great once again.23

THE WEIMAR REPUBLIC [18:00-19:51]

The Weimar Republic was under assault from both sides of the political spectrum. German democracy was new and feeble. Most Germans were uncommitted to it, and many outright preferred monarchy and militarism.

In 1919, leftists in Munich attempted independence and declared themselves to be a Soviet-like republic. It quickly fell. The following year, army officers and right-wing politicians attempted a coup. It also quickly collapsed. But the point remains—things were far from stable.

The debt was another problem. Remember how Germany owed all that money to the Allies? Well, in 1922, the Weimar Republic defaulted on its payments.

In response, France seized the Ruhr, Germany’s industrial center in January of ‘23. Under duress, Germany responded by simply printing more money, which created an economic disaster. The value of the German mark plummeted. The money became worthless. A trip to the grocery store required bringing literal wagons of cash. Half a pound of apples cost 300 billion marks. The price of a loaf of bread would cost in the trillions. Germans found that their lifesavings, sitting in a bank, were now worthless.24

Hyperinflation in Berlin, October 1923. CC-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons.

FAILED NAZI COUP [19:51-21:49]

In November 1923, hoping to capitalize on the crisis, the Nazi Party attempted to overthrow the Republic.25

On the night of November 8th, before a crowd of 3000 supporters, Hitler and other Nazi leaders declared a national revolution and marched on the war ministry in Munich. The event failed to incite the revolution that Nazi leaders had hoped. The coup was crushed the following morning, and fourteen Nazis were left dead.

Hitler and other party leaders were arrested. He served a brief prison sentence during which he wrote his manifesto called My Struggle, or in German “Mein Kampf.”26

New German leadership negotiated an end to the occupation of the Ruhr Valley, and the government stopped printing money. By 1924, the German economy was stable. In fact, the mid-1920s were the “Golden Years” of the Weimar Republic.27

Throughout the decade, the Nazi Party remained small and on the fringes. The core of the party were young men, particularly the disillusioned veterans of the First World War. It also appealed to the middle class by working against local officials whom they claimed were corrupt or by rallying the public against Jewish influence in German society. By 1928, the party had a total of 110,000 members.28

MANCHURIA [21:49-26:40]

Meanwhile, another conflict was growing in the Pacific.

The Chinese government in the early 20th century was weak and vulnerable to foreign influence. In 1905, Russia and Japan had fought a war for access to Manchuria, a region in northern China. In the end, though Manchuria was still technically part of China, Russia and Japan divided influence in there among themselves. Russia operated the Chinese Eastern Railroad while Japan operated the South Manchurian Railroad, giving each claim to the region’s resources. The Japanese were even allowed to station troops in China along the narrow railroad zone.29

In the late 1920s, however, the Chinese government attempted to regain control of Manchuria. Chinese president Chiang Kai-shek encouraged migration to the region and the boycott of Japanese goods. He looked to construct his own railroad line, running parallel to the one under Japanese control.30

Japan was alarmed. Manchuria provided food and resources that Japan needed, and there was growing sentiment that their country should not be reliant on outside resources from a foreign territory. Manchuria was sparsely populated, rich in resources, and it could buffer Japan from now-Communist Russia. Why not just take it outright?31

To understand what happened next, we need to understand the Japanese form of government at the time. Japan had a civilian government lead by a prime minister. It also had an emperor—Emperor Hirohito assumed the throne in 1926. Neither the prime minister nor the emperor held the true power.

The prime minister was essentially subservient to the military. Military leaders could withdraw their members from the prime minister’s cabinet, which would cause the administration to topple. And, in 1931, military leaders even assassinated Prime Minister Tsuyoshi. The military reported directly to the emperor. The emperor, however, was more of a figurehead and held little practical power. Bottom line, the military ran the show.

When the civilian government sought to negotiate an end to the tensions in Manchuria, the military grew frustrated and stepped into action. In September of 1931, they secretly blew up a section of their own railroad in Manchuria, then blamed China and used the incident to take full control of the region. China appealed to the League of Nations.32

The League, limited in authority to interfere, didn’t do much except call for a peaceful resolution—thanks guys, big help. Japan took full control of Manchuria over the following months. In 1932, they installed a puppet state headed by a member of the previous Chinese dynasty, lending it some credibility. But Japan held the real power. They sent over 600 men to be “advisors” to the new government.33

Map including Manchukuo, the Japanese controlled area historically known as Manchuria, circa 1939. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license, via Wikimedia Commons.

The League of Nations refused to recognize this new state. So, Japan withdrew from the League.34 The incident reveals both the League’s inability to halt a belligerent nation and the deep reluctance of Western powers to get involved in another conflict. The shadow of World War I hung over the world. And the Great Depression, which began in 1929, now absorbed the attention of the world’s political leaders.

NAZI BREAKTHROUGH [26:40-30:25]

The Depression spelled the end of the Weimar Republic. By 1930, 3 million Germans were unemployed. The economic crisis further radicalized the German public—they wanted someone to take control. The Nazis received 6.4 million votes in the 1930 election. They commanded 107 seats in the Reichstag, the second most of any party. Two years later they won another 113 seats. Though not an outright majority, they were now the largest party in Germany. Since Hitler was the leader of the party, President Paul Von Hindenburg appointed him as Chancellor.35

In February 1933, a fire broke out in the Reichstag building. The Nazis capitalized on the situation. Hindenburg granted Hitler emergency powers, which limited civil rights and allowed him to detain civilians without a trial. Then, in March ‘33, the Reichstag granted Hitler power which superseded the constitution and protected him from all political accountability.

But the Nazis did bring about a certain kind of order. They ended political violence on the street by crushing dissent. Hitler seized control of Germany’s press and universities. By July of ‘33, all other parties were made illegal, thus ending the threat of communism and parliamentary infighting. In short, the Nazis offered stability—authoritarianism often does.36

Then, on August 1, 1934, President Hindenburg died. The Reichstag then passed a law eliminating the office of President and conferred on Hitler a new title—Fuhrer. Later that month, all military and public officials were required to swear an oath of loyalty, not to Germany or the constitution, but to Hitler himself. He became the embodiment of the German nation.37

So, how did democracy die in Germany? Well, the people voted for the Nazis. Then, government officials voted to give Hitler his power. Democracy killed itself.38

Americans, meanwhile, caught in the throes of the Great Depression, were largely preoccupied and unconcerned.

Franklin Roosevelt was inaugurated in March of ‘33, as Hitler was consolidating his power. In Roosevelt’s inaugural address, he offered only one sentence on foreign policy. “I favor as a practical policy the putting of first things first.” The Depression, not global affairs, was the chief concern of the American people and its president.39

ETHIOPIA [30:25-31:55]

But the storm of war was brewing.

In Italy, Mussolini wanted an empire. He envisioned the entire Mediterranean again becoming a “Roman lake.” But first, he wanted Ethiopia. Italian forces had suffered a humiliating defeat there back in 1896. Conquering the country would restore national pride, which is important to nationalists.

Italy launched an invasion of Ethiopia in the fall of 1935. Emperor Selassie appealed to the League of Nations for help. The League offered a half-hearted response. It placed sanctions on Italy but did not prohibit the sale of oil, which allowed Italian forces to continue. The British even allowed Italian ships through the Suez Canal on their way to Ethiopia. Italian forces captured Addis Ababa, the Ethiopian capital, in May of 1936. 500,000 Ethiopians were killed in the battle. The sanctions were lifted soon after, and Italy quit the League of Nations.40

AMERICAN NEUTRALITY [31:55-33:10]

How did Americans respond? Over the following years, Congress passed a series of neutrality acts aimed at keeping the US out of war. The first act prohibited loans and the sale of arms to nations at war. Roosevelt, who always sought maximum political flexibility, argued for allowing a distinction between an aggressor nation and its victim. But he needed the votes of isolationists to pass his New Deal legislation, and it wasn’t worth the political fight, so Roosevelt reluctantly signed the Neutrality Act in August of 1935.

In 1936, Congress renewed the Neutrality Act. The vote in the House was 353 to 27.41

Americans did not want to get involved in another war.

THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR & NEUTRALITY [33:10-37:04]

In 1931, a revolution had overthrown the Spanish monarchy and replaced it with a republic. Made up mostly of leftists, they attempted to weaken the military, decrease the power of the Catholic Church, and break up the estates of wealthy landowners. The wealthy, the church, and the military did not care for these policies.42

In the election of 1936, leftists won big. In response, Spanish General Francisco Franco, then stationed in Morocco, began a rebellion against the republican government.

The Spanish Civil War captured the attention of Europe. By the end of July, both Hitler and Mussolini provided Franco with tanks, planes, and soldiers. By November, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin provided aid to republican forces in Spain, since it included both leftists and communists. War-weary Britain refused to sell arms to either side.43

The American people were divided on the war in Spain. American Catholics hated the brutality of the Republic against the clergy. On the other hand, the cause of the Spanish fighting for their republic struck a chord with many young men. Several thousand Americans traveled to France and snuck across the Spanish border to join the fight against Franco.44

Most Americans, however, were indifferent. A survey in 1937 found that two-thirds of Americans had no opinion on the Spanish Civil War.45

That same year, when the Neutrality Act was again set to expire, Congress renewed and expanded it, applying it to international conflicts and civil wars. Roosevelt still preferred more flexibility but reluctantly signed the bill.46

Congress was also forced to grapple with the sale of non-military goods. America wanted to remain neutral, but a full embargo with nations at war would damage the economy. Could America have both peace and prosperity? The solution Congress reached was the so-called “Cash and Carry” system. Nations at war could buy non-military goods but only if they paid cash and transported them in their own ships, hence “cash and carry.”47

Germany and Italy, meanwhile, supplied Franco’s rebels, so America’s decision not to sell arms to either side really only hurt the Spanish Republic. And in 1939, Franco’s forces succeeded in overthrowing the Republic—yet one more dictatorship in Europe. Plus, the relationship between Italy and Germany grew stronger as a result of their mutual involvement in Spain. Mussolini even visited Germany in September of 1937.48

Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini in Munich, Germany, ca. June 1940. Eva Braun, part of Eva Braun's Photo Albums, ca. 1913 - ca. 1944, National Archives and Records Administration. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Roosevelt later reflected that failing to aid the Spanish government had been a great mistake. Many Americans later came to the same conclusion.49 But not yet.

JAPANESE IN CHINA [37:04-39:45]

Soon after the 1937 Neutrality Act was signed, Japan launched a full-scale invasion of China. Japanese troops captured Nanking, the capital city, in December.

What followed is called the “Rape of Nanking.” In the ensuing six weeks, Japanese soldiers pillaged the city, looting and burning down buildings. Chinese women were especially vulnerable. Countless women were raped. Some were even forced into prostitution. In mass executions, they killed men, women, and children. In the end, Japanese forces killed somewhere between 200,000 and 300,000 Chinese in Nanking alone.50

The Chinese continued to fight the Japanese invasion, and it was a long and bloody affair.

Now, back in the 1850s, the US had negotiated to keep a naval presence along the Yangtze River in China to protect American interests there. In 1937, when Japan took Nanking, one US ship, the Panay took aboard about a dozen Americans, most of them serving in the U.S. State Department, as well as several hundred Chinese civilians, who were working for American businesses.51

While waiting in the Yangtze Channel, Japanese aircraft dropped a bomb on the ship, killing two and wounding 30 more. Japan quickly apologized for the incident and agreed to pay the US reparations of $2 million.52 But how would the American people respond?

The Panay incident seemed to only reaffirm America’s commitment to isolationism. Only a generation before, in 1898, the sinking of the USS Maine had initiated the Spanish-American War. But in this case, one senator said the lesson was that Americans should “get the hell out of China war zones.”53

GERMANY REARMAMENT & THE RHINELAND [39:45-41:35]

Though they had been victorious, Britain and France were exhausted by World War I. They desperately wanted to avoid another war. Germany desperately wanted redemption.

In the fall of 1933, Germany withdrew from the League of Nations. Then, Hitler codified his racial beliefs in the Nuremberg Laws in 1935. The laws officially designated Jews as non-citizens, limited their employment options, restricted civil rights, and prohibited marriages between Jews and non-Jews, labeling it as “race defilement.”54

Hitler also built up the military. The Rhineland is a region of Germany which borders France. According to the Treaty of Versailles, the Rhineland was supposed to remain demilitarized. That is, German territory with no German military presence.55

In violation of the treaty, Hitler sent troops to the region in March of 1936. He quieted international resistance by calling for peace and suggesting that Germany may rejoin the League of Nations, thus exploiting the war-weariness of the Allies. Then, he ramped up military spending. By 1938, arms production consumed 52% of the German budget.56

AUSTRIA & CZECHOSLOVAKIA [41:35-45:27]

Austria and Czechoslovakia were the first targets in Hitler’s conquest of Europe. Unification of all German people was a core tenant of Nazi ideology, and both countries had large German populations.

In February of 1938, Hitler invited the chancellor of Austria to a meeting. Essentially, Hitler bullied him into legalizing the Austrian Nazi Party. The chancellor then called for a public vote on Austrian independence—the people could decide whether to join Germany.

Rather than leave it to that, Hitler sent German troops to invade Austria. Most Austrians welcomed Nazi forces. When a public vote was later held, both sides approved of Austria’s annexation. Hitler now had access to Austrian resources, gold, and manpower.57

Hitler then turned his attention to Czechoslovakia. There were 3 million ethnic Germans living in that country, most of them in the region of Sudetenland. In May 1938, Hitler sent German troops to the border, ready to move into Czechoslovakia.

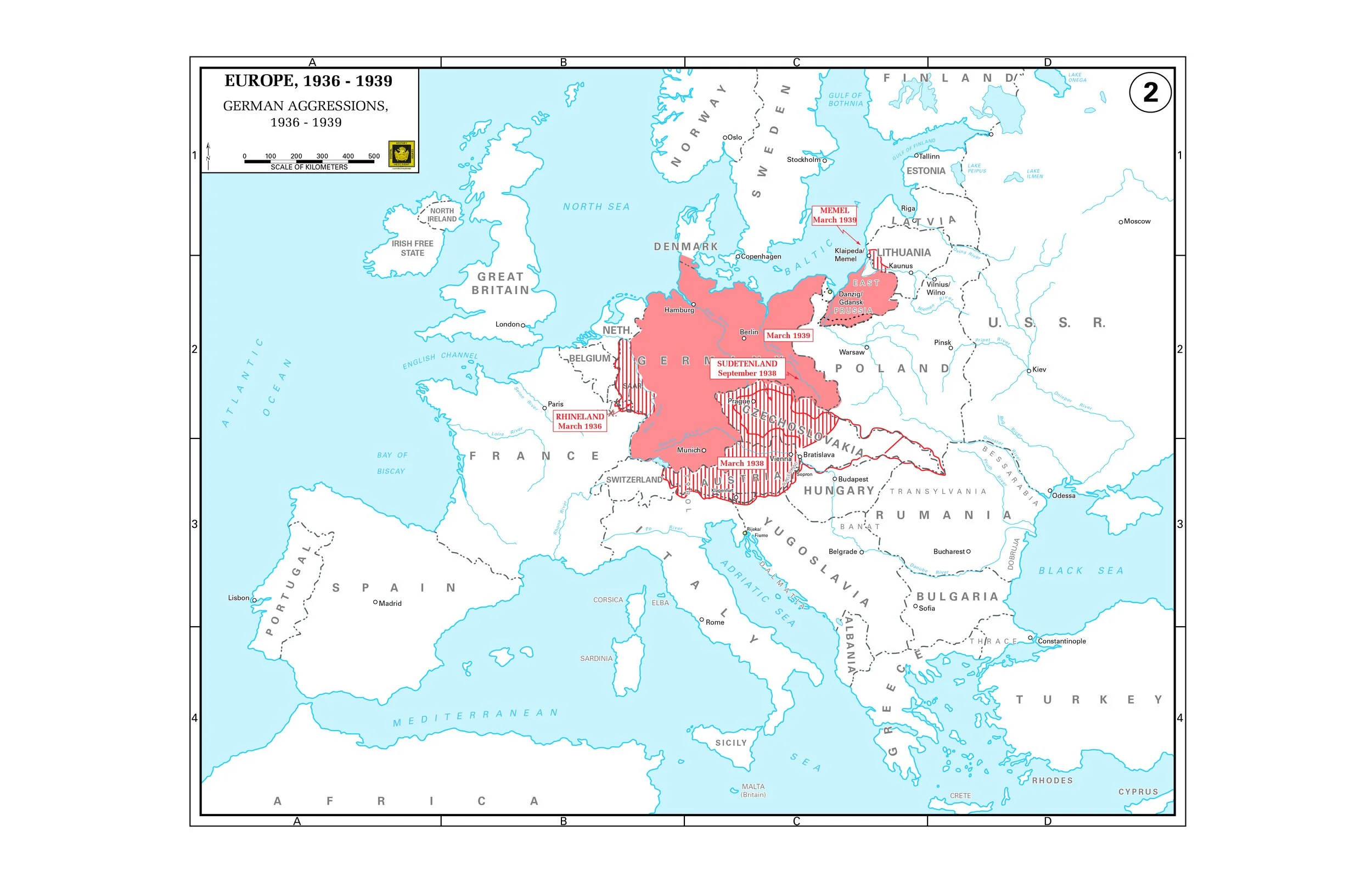

German expansion, 1936-39. Atlases, Digital History Center, Department of History at the United States Military Academy.

In Britain, Neville Chamberlain had been elected Prime Minister the previous year. His foreign policy was one of appeasement. Chamberlain believed that Hitler could be appeased with new territory and that war could be avoided. Chamberlain recognized that there was a logic in Hitler’s goal of uniting Germans into a single state—it was the logic of nationalism. But above all, appeasement was born out of a desire to avoid a repetition of the horrors of World War I.58

Chamberlain, joined by French Prime Minister Edouard Daladier and Mussolini, met with Hitler in Munich in September 1938.Without inviting anyone from Czechoslovakia to the meeting, the men agreed to cede the Sudetenland to Germany. Hitler promised, “This is the last territorial claim I have to make in Europe.”59

Chamberlain returned to London and was met by a crowd of cheering Britons. He declared that there would be “peace in our time.” Future Prime Minister Winston Churchill, however, said “this is only the beginning of the reckoning.”60

Of the two men, Churchill was right. The agreement bought time for Hitler to further prepare the German military. And, in March of 1939, six months after the Munich Agreement, Hitler broke the treaty and sent troops over the newly drawn border and seized all of Czechoslovakia.

It was natural that many men wanted to avoid another war, but appeasement was delusional. Even Chamberlain came around. There was no satisfying Hitler, and no treaty meant anything to him. Britain and France then declared their support for Poland, likely the next target in Hitler’s conquest.61

NAZI-SOVIET PACT [45:27-46:59]

Hitler knew that an invasion of Poland would bring war, so he secured his own alliance. In May 1939, Hitler signed the “Pact of Steel,” a military alliance with Italy. Their alliance was called the Axis.

And in a move that shocked the world, Germany and the Soviet Union agreed to a nonaggression pact. They also secretly agreed to divide Poland among themselves. Hitler believed communists were “the scum of the earth.” He secretly planned to eventually invade and conquer the Soviet Union; but in the meantime, a pact would hopefully crush the will of Britain and France to fight.

After the Nazi-Soviet Pact, the world sat and waited. Then, on September 1st, 1939, 1.5 million Nazi forces invaded Poland. In response, on September 3rd, both France and Britain declared war on Germany. World War II had begun.62

AMERICAN RESPONSE TO WAR [46:59-48:24]

America hoped to stay out of World War II, but President Roosevelt understood the threat the Nazis posed earlier than most Americans and sought to aid Great Britain and France. To do so, however, he needed to revise the Neutrality Act. Only two weeks after the war began, he called for a special session of Congress. Roosevelt put his full political weight behind revising the act, something he had never done with a foreign policy issue.

The debate that followed lasted six weeks and, in the end, produced a compromise. Under the new act, the arms embargo was lifted. The US could again sell weapons to nations at war, but the “cash and carry” policy remained. This meant nations would have to pay cash and then transport the goods on their own ships. Roosevelt signed the Revised Neutrality Act in November of 1939, and America began selling weapons to Britain.63

But would it be enough to stop the Nazis?

GERMANY TAKES EUROPE [48:24-51:39]

Poland fell by the end of September of ‘39 and, as agreed upon, was divided between the Nazis and the Soviets. The Soviets also invaded Finland over the winter.64

In Western Europe, winter brought a pause in the fighting, but the conflict bloomed again in spring. In April, Germany invaded neutral Denmark, which surrendered without a fight. Then, German troops quickly moved into Norway. Paratroopers landed in the port cities and more soldiers followed by sea. French and British soldiers tried to repel the invasion but were overwhelmed. They pulled out, and Norway fell to the Nazis in May. The stunning defeat was the death knell for the Chamberlain government. He was removed as British Prime Minister, and Winston Churchill took his place.

The “Low Countries” fell next. German planes bombed Rotterdam in the Netherlands, destroying the city center and killing 40,000 people. 1800 German tanks cut through the forests of Belgium which, like Luxembourg and the Netherlands, also fell to the Nazis in May 1940.65

Before Belgium even surrendered, German forces moved into France, smashing through their defenses. The Nazis captured Paris on June 14th, and the next week Italy entered the war and invaded from the south. And France, too, fell to the Axis. Hitler did in a few weeks what the German army had been unable to do in all of World War I.66

Hitler in Paris, June 1940. Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-H1216-0500-002 / CC-BY-SA, CC BY-SA 3.0 DE, via Wikimedia Commons.

Americans watching this were likely thinking, “holy shit, is Hitler going to conquer Europe?!” After only eight months of fighting, Britain alone was left to oppose the Nazis.

How exactly did this happen?

The Nazi strategy was called the “blitzkrieg,” which is German for “lighting war.” The German army was built for speed. Soldiers moved on motorized vehicles in coordination with armed tanks. They launched surprise attacks, broke through enemy lines and snuck deep in their opponent’s territory, causing shock and confusion. Meanwhile, their air force bombed airfields, destroying enemy planes while they were still on the ground.67 Nazi soldiers fought with a terrible fury. It was the opposite of the trench warfare of World War One.

German expansion meant that vast numbers of European Jews were now under Nazi rule.

JEWISH REFUGEES [51:39-55:19]

Some Jews attempted to relocate to the United States, but American immigration laws presented a problem. Restrictive laws capped immigration at 150,000 immigrants per year. Within that number were quotas assigned by country of origin. Furthermore, American immigration laws made no exception for refugees or asylum seekers.68

When Germany annexed Austria in March 1938, many Austrian Jews attempted to flee to America. The American Consulate in Germany was overwhelmed. An average of 3000 Jews applied for visas every day, but the American Consulate was only allowed to issue 850 visas a month. Roosevelt took what little action he could. He merged the quotas of Germany and Austria and prioritized Jewish immigrants, allowing 50,000 Jewish refugees to flee Nazi rule over the following two years.

In early November 1938, a Jewish refugee killed a German diplomat in Paris. Nazis responded with the Kristallnacht, the “night of broken glass.” On the night of November 9-10, Nazis looted the homes of German Jews, sacked their businesses, and set their synagogues on fire. Then, the Nazis arrested 20,000 Jewish “criminals” and forced the Jewish community to pay for the damage. Roosevelt, his hands tied by the immigration laws, responded by recalling the American ambassador to Germany and extending the visas for Jews in America. Many Americans spoke out against Jewish persecution but were satisfied to offer words only. A survey in 1939 found that most Americans did not support taking in Jewish refugees.

In May of that year, a ship called the St. Louis, with 930 Jewish refugees aboard, departed Europe for the Americas. It went first to Cuba, but they were refused entry. The ship then sailed north up the Atlantic coast, hoping to be received. When US officials denied them, the ship was forced to return to Europe. The captain was able to divide up the refugees and secure them entry into Holland, Belgium, France, and Britain. Those who went to Britain were safe. But, within two years, every other country fell to Germany, and those passengers were again under Nazi rule—254 were killed, most of them in concentration camps.69

American inaction had deadly consequences.

US AID TO BRITAIN [55:19-57:33]

The fall of France began to wake Americans up to the danger the Nazis posed. Having long felt protected from European wars by the Atlantic Ocean, the fury of the blitzkrieg was a shock. Modern technology had shrunk the world. It helped shift the attitude of the public, and national defense became a priority.70

On June 4th, 1940, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill gave perhaps his most famous speech. He appeared before Parliament, reaffirmed British resolve, and looked to America. The speech was broadcasted into the homes of millions of Americans.

“We shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be,” said Churchill, “we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender…until, in God’s good time, the New World, with all its power and might, steps forth to the rescue and the liberation of the old.”71

Britain would stand and fight, but it could not last long without American aid. To Roosevelt, Churchill asked for weapons—destroyers, aircraft, ammunition, and steel.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill portrait by Yousuf Karsh titled “The Roaring Lion,” 1941. Yousuf Karsh, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 1933. Elias Goldensky, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Roosevelt grew bolder in his actions. He weeded out isolationists in his administration. He fired the Secretary of War and the Secretary of the Navy. Though he was a Democrat, in their stead he appointed two Republicans, both of whom were internationalists.72

ROOSEVELT & THIRD TERM [57:33-59:54]

In the opening months of 1940, Roosevelt gave every indication that he would honor the presidential tradition started by George Washington and retire after two terms. He oversaw the construction of new buildings at his home in Hyde Park and planned to establish his presidential library. But the war in Europe made him reconsider his plans. “I don’t want to run,” he privately confessed, “unless…. things get very, very much worse in Europe.” And when they did, Roosevelt decided to break with tradition and run for a third term as president.73

Roosevelt was in for a fight. In July 1940, isolationists founded the America First Committee. The organization was committed to keeping the US out of the war and was against providing aid to Britain. At its height, the committee had 850,000 members organized into 450 local chapters. Their celebrity spokesman was the famed pilot, Charles Lindbergh.74

Lindbergh held many anti-Semitic beliefs. In an antiwar speech in September 1941, he claimed that Nazis were not a threat. “The greatest danger to this country,” he said, “lies in [Jewish] ownership and influence in our motion pictures, our press, our radio and our government.”75

Lindbergh had visited Germany several times in the 1930s and was even honored by the German government in 1938. Privately, Roosevelt claimed he was convinced Lindbergh was a Nazi.76

And, while America dragged its feet, the war continued in Europe.

BATTLE OF BRITAIN & DESTROYER DEAL [59:54-01:02:52]

A Nazi invasion of Britain would require control of the air. So, Hitler sent his air force across the English Channel in what’s called the Battle of Britain. It lasted four months, July to October 1940. German pilots at first targeted Britain’s airfields. Then, they changed their tactics and began bombing British cities, terrorizing civilians. Londoners took refuge in underground shelters and subway stations. Children were evacuated to the countryside to avoid the nightly bombings. But, capitalizing on their own speedy airplanes and new radar technology, the British air force heroically defended their island.77

View along the River Thames in London towards smoke rising from the London docks after an air raid during the Blitz, September 1940. New York Times Paris Bureau Collection, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Roosevelt, meanwhile, was determined to get them aid but faced several problems at home. In May, Churchill had requested 40-50 American destroyers for the British Navy. They didn’t have to be new, old holdovers from World War I would suffice. Roosevelt wanted to send them, but military leaders opposed the transfer. And Congress, also concerned about the amount of aid flowing to Britain, prohibited such a deal unless military leaders confirmed that such equipment was surplus.78

Roosevelt essentially forced the military to declare that the destroyers were obsolete. Then, instead of selling them to Britain, he traded them in exchange for British naval bases in the Atlantic, which gave the appearance of protecting the Western Hemisphere. He also secured a private promise from Republican nominee Wendell Wilkie not to make the destroyer deal a campaign issue in the 1940 presidential election. Finally, he authorized the whole plan by executive order and bypassed Congress.79

In an election year for an unprecedented third term, this was a gamble. He was stretching his political power to its constitutional limit and arguably beyond it. But public opinion was slowly turning. In their own homes, Americans listened to coverage of the Battle of Britain on their radios. The resolve of the British people was inspiring, and more Americans came to support providing them with aid.80

AMERICA INITIATES DRAFT [01:02:52-01:04:19]

While they still hoped to stay out of it, political leaders worked to get the country ready…just in case. When the war began, the American military was a little smaller than Switzerland’s, made up of 245,000 volunteer servicemen. George Marshall, the Army Chief of Staff, claimed that those numbers were insufficient. So, in September 1940, Congress passed the first ever peace-time draft. All men ages 21-36 were required to register—a pool of 16.5 million. The military could now call up to 900,000 men annually for a 12-month term, after which the men would enter the reserves.81

So, Britain got the destroyers. America initiated a draft. In October, Hitler abandoned his plan to invade Britain. And in November, Roosevelt became the only president to ever win a third term.82

LEND-LEASE & ATLANTIC CHARTER [01:04:19-01:06:40]

Soon after Roosevelt’s reelection, Churchill sent him a message. “Britain's broke,” he explained. It would no longer have the funds to pay cash for American arms. Roosevelt acted quickly. The solution to the problem became known as the Lend-Lease Policy. He went to Congress to pass the “Bill to Promote the Defense of the United States.” Britain was the guardian of the Atlantic, he argued. Its defense protected America. The bill would grant the president the power to “sell, transfer, exchange, lease, or lend…war material” to any nation whose defense protected the US. America, Roosevelt said, must become the “great arsenal of democracy.”

Isolationists fought hard against the bill. Some argued it would make Roosevelt a dictator. One senator claimed the bill would lead to war and the death of a quarter of America’s young men. But the tide was turning. The bill passed in March 1941. It eventually led to $31 billion in aid to the British.83

In the summer of ‘41, Churchill and Roosevelt arranged for a secret meeting.

Roosevelt, supposedly on a fishing trip off the coast of Connecticut, traveled by ship up the Atlantic. He and Churchill met off the coast of Newfoundland. There the men crafted the Atlantic Charter. The statement called for the “final destruction of Nazi tyranny” and clarified that Britain and the US sought no new territory in the war.84

America was not yet in the war, but it was getting close.

GERMANY INVADES SOVIET UNION [01:06:40-01:09:30]

Simultaneously, the war took a dramatic turn in Europe. Though Hitler had signed a nonaggression pact with the Soviet Union in 1939, his aim was always to conquer his supposed ally. In June 1941, he launched Operation Barbarossa —a massive invasion of the Soviet Union. 3.2 million German soldiers in 148 divisions stretched across a thousand-mile front, from the Article Circle to the Black Sea.85

German invasion of Soviet Union, known as Operation Barbarossa, June 1941. R.D. Hooker, Jr., Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

One army struck at Leningrad, modern day Saint Petersburg, and besieged the city in September of 1941. Another army captured 250,000 prisoners near Minsk and then moved towards Moscow. A third struck at Kiev. By the end of the year, the Nazis captured a million square miles of Soviet territory.86

…And they unleashed their terror on the people. Before the year was out, they took roughly 3 million soldiers as prisoners of war. They left villages in ruins, seized food, executed civilians, and they killed roughly one million Jews in mass executions.87

But then the Nazis encountered Russia’s greatest advantage—winter. Hitler and his generals had assumed the Soviets would fall quickly. They underestimated Soviet resistance and were unprepared for a drawn-out fight. Oil froze, guns froze, soldiers froze too. In December ‘41, Germans reached a mere 20 miles outside of Moscow, but they were forced to pull back. 1.3 million German soldiers died in the campaign.88

Despite their initial losses, the Soviets refused to surrender. Back in the US, Roosevelt persuaded Congress to extend the Lend-Lease program to the Soviet Union. By the end of the war, the Soviets received $10 billion dollars in aid from the United States.89

CONFLICT IN THE PACIFIC [01:09:30-01:12:31]

Despite all the attention given to Europe, it was actually the conflict in the Pacific that drew the US into the war.

The Japanese invasion of China had turned to a stalemate. Internal frustration toppled yet another administration. Prince Fumimaro Konoe, the former prime minister, resumed the position in 1940. General Hideki Tojo became the war minister. Both men sought to end the conflict in China through a crushing defeat, with no negotiation.90

Japanese General Hideki Tojo, circa 1945. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

In 1940, while engulfed in the Nazi blitzkrieg, many European empires were forced to leave their colonies in Asia virtually defenseless. In July, Japan seized the opportunity and invaded French Indochina. They also eyed the Dutch and British East Indies. Control of those territories would provide Japan with natural resources and cut-off China.91

Then, in September, Japan signed the Tripartite Act with Italy and Germany, joining the Axis Powers.92 The two conflicts—one in Europe, the other in Asia—were now united.

Roosevelt hoped to limit Japanese expansion without outright conflict, so he sought to limit their resources. At this time, Japan’s military relied heavily on oil and steel imported from the US. To deter further Japanese expansion, Roosevelt signed the National Defense Act in July 1940. The act gave the president the power to declare certain goods vital to national defense and to therefore limit their exportation from the country.93

Like the rest of the world, Japan was shocked when Hitler invaded Russia. Japanese leadership was faced with a tough decision—continue to strike south into the weakened European colonies or turn north and attack Russia as well. Ultimately, military leaders settled on the southern plan in July 1941. Japanese troops moved from Northern Indochina into the South, preparing to move next into either British Malaya or the Dutch East Indies. From there, they would be in a prime location to attack the Philippines, which was a colony of the US.94

ROOSEVELT & JAPAN [01:12:31-01:15:01]

Roosevelt then took stronger action to limit Japanese control of the Pacific. Invoking the National Defense Act, he cut off American oil to Japan and froze Japanese assets in the US.

This left Japan with only enough oil stores to supply its military for 18 months. In early September, Japanese leadership determined that, if they could not regain access to American oil by negotiation, they would need to seize the Dutch East Indies, which could supply the oil they needed. To hold those islands and ensure naval supremacy in the Pacific, Japan would also need to take the British naval base in Singapore and destroy the US fleet which was stationed at Pearl Harbor.

It was an ambitious plan. But would it be necessary?

As the situation escalated, Prime Minister Konoe was ousted from his position. General Tojo took his place.95

Roosevelt considered a negotiated solution to the tensions in the Pacific. Japanese diplomats floated a potential deal where the US would recognize Japanese claims in China, hopefully leading to China’s full surrender. The US, then, could avoid war in the Pacific and focus on the conflict in Europe. Roosevelt toyed with the idea. BUT, if China were to fall, Japan could turn its focus to the north, invade Russia, divide Soviet resources, and strengthen Hitler’s control of Europe. World wars are complicated.

Ultimately, the US rejected the deal in November 1941. Roosevelt knew that doing so almost certainly meant war. He was right. Privately, Japanese leadership agreed that if no deal was reached by November 30th, they would launch their plan.96

PEARL HARBOR [01:15:01-01:16:47]

On the morning of December 7th, 1941, 187 airplanes departed from a fleet of Japanese aircraft carriers in the Pacific and flew south to the Hawaiian island of Honolulu. Their target was the American naval base at Pearl Harbor.

The attack was a complete surprise. 230 US airplanes were stationed at the base, the attack destroyed 152 of them and sunk 5 of 8 US battleships. 2400 Americans were killed.97

Photograph of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii on December 7, 1941, just as the USS Shaw exploded. The stern of the USS Nevada can be seen in the foreground. National Archives and Records Administration, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The attack rallied the Nation behind war like nothing else could. American isolationism evaporated.

The following day, President Roosevelt appeared before Congress. “Yesterday,” he began, “December 7, 1941—a date which will live in infamy—the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan.”98

Roosevelt asked that Congress issue a declaration of war against Japan. Congress granted it. Three days later, Germany, Japan’s ally, declared war on the US and the US did the same in return.99

CONCLUSION [01:16:47-01:19:11]

The shadow of World War I hung over the world. Exhausted and war-weary, the victorious countries hoped to avoid another conflict, while Germany sought to redeem itself after defeat. The United States came to see its own entry into the First World War as a mistake. It wanted to avoid making it twice. The problem was that World War II was not World War I, but it took a long time for many Americans to see the difference.

The Japanese military took control of their government and sought an empire while democracies in Europe crumbled, and the Nazis unleashed a genocidal nightmare.

American isolationists, meanwhile, aimed to keep the country out of the fight. But President Roosevelt, seeing the conflict for what it was long before the public, sought to aid American allies in whatever way he could.

With all the attention given to Europe, it is perhaps ironic that it was the conflict in the Pacific which finally drew America into the war. Isolationism died with the attack on Pearl Harbor.

And, on December 8th, 1941, America finally entered World War II.

Thanks for Listening.

[American History Remix is written and produced by Will Schneider and Lyndsay Smith. For the latest updates, be sure to follow us on Instagram and Threads. Check out our website for episode transcripts, recommended reading, and resources for teachers. That’s AmericanHistoryRemix.com.]

REFERENCES

Caplan, Jane, ed. Nazi Germany. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Doenecke, Justus D. and John Edward Wilz. From Isolation to War, 1931-1941. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Wiley Blackwell, 2015.

Herring, George C. From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Howard, Michael. The First World War: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Kennedy, David M. Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Kreis, John F. “Blitzkrieg in Poland.” Air Power History 36, no. 3 (1989): 31-35.

Leuchtenburg, William E. Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, 1932-1940. New York: Harper & Row, 1963.

Merriman, John. A History of Modern Europe: From the Renaissance to the Present. 3rd ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2009.

Snyder, Timothy. Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. 2nd ed. New York: Basic Books, 2022.

Weinberg, Gerhard L. A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

NOTES

1 David M. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 386. Quoted in William E. Leuchtenburg, Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, 1932-1940 (New York: Harper & Row, 1963), 197n1.

2 Michael Howard, The First World War: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 29.

3 John Merriman, A History of Modern Europe: From the Renaissance to the Present, 3rd ed. (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2009), 892-95, 924.

4 Merriman, A History of Modern Europe, 914.

5 Merriman, A History of Modern Europe, 916.

6 Justus D. Doenecke and John Edward Wilz, From Isolation to War, 1931-1941 (Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Wiley Blackwell, 2015), 8. George C. Herring, From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 412.

7 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 418-19.

8 Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 6-7.

9 “World War I Centennial Commemoration,” Veterans of Foreign Wars, accessed April 17, 2025, https://www.vfw.org/media-and-events/commemorations/world-war-i-centennial-commemoration.

10 Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 387. Doenecke and Wilz, From Isolation to War, 8.

11 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 502.

12 Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 386. Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 502-04.

13 Merriman, A History of Modern Europe, 961.

14 Merriman, A History of Modern Europe, 1006.

15 Merriman, A History of Modern Europe, 1007.

16 Merriman, A History of Modern Europe, 1007-08.

17 Merriman, A History of Modern Europe, 1007-09. Doenecke and Wilz, From Isolation to War, 74.

18 Merriman, A History of Modern Europe, 1008. “Benito Mussolini,” TIME, accessed March 8, 2024, https://content.time.com/time/covers/0,16641,19230806,00.html.

19 Merriman, A History of Modern Europe, 920-21. Gerhard L. Weinberg, A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 8.

20 Howard, The First World War, 116. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 1-2.

21 “The Weimar Republic (1918-1933),” Deutscher Bundestag, accessed March 8, 2024, https://www.bundestag.de/en/parliament/history/parliamentarism/weimar/weimar-200326.

22 Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 8.

23 Richard J. Evans, “The Emergency of Nazi Ideology,” in Nazi Germany, ed. Jane Caplan (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 31, 45-46. Weinberg, A World at Arms, 20-21.

24 Merriman, A History of Modern Europe, 957, 983-85.

25 Peter Fritzsche, “The NSDAP 1919-1934: From Fringe Politics to the Seizure of Power,” in Caplan, Nazi Germany, 57-58.

26 Fritzsche, “The NSDAP 1919-1934,” 58-59.

27 Merriman, A History of Modern Europe, 985-86.

28 Fritzsche, “The NSDAP 1919-1934,” 60-65. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 8.

29 Doenecke and Wilz, From Isolation to War, 22. Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 486.

30 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 486-87.

31 Doenecke and Wilz, From Isolation to War, 31-32.

32 Doenecke and Wilz, From Isolation to War, 33-34. Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 488.

33 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 489-90. Doenecke and Wilz, From Isolation to War, 54.

34 Doenecke and Wilz, From Isolation to War, 54-55.

35 Fritzsche, “The NSDAP 1919-1934,” 69.

36 Fritzsche, “The NSDAP 1919-1934,” 70-71. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 384.

37 Jeremy Noakes, “Hitler and the Nazi State: leadership, hierarchy, and power,” in Caplan, Nazi Germany, 73-74.

38 Fritzsche, “The NSDAP 1919-1934,” 70.

39 Doenecke and Wilz, From Isolation to War, 60-64. Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 484.

40 Merriman, A History of Modern Europe, 1007, 1033-34. Doenecke and Wilz, From Isolation to War, 73, 75, 82-83.

41 Doenecke and Wilz, From Isolation to War, 82. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 397.

42 Doenecke and Wilz, From Isolation to War, 83-84.

43 Doenecke and Wilz, From Isolation to War, 84.

44 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 507-08. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 399.

45 Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 398-99.

46 Doenecke and Wilz, From Isolation to War, 88. “Neutrality Acts, 1930s,” Office of the Historian, accessed July 23, 2024, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1921-1936/neutrality-acts. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 400.

47 Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 400. Doenecke and Wilz, From Isolation to War, 88-90.

48 Gerhard L. Weinberg, “Foreign Policy in Peace and War,” in Caplan, Nazi Germany, 204-05.

49 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 508.

50 Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 401. Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 510-11.

51 Doenecke and Wilz, From Isolation to War, 99.

52 Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 402.

53 Doenecke and Wilz, From Isolation to War, 100. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 402.

54 Doenecke and Wilz, From Isolation to War, 66. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 410. Nikolaus Wachsmann, “The Policy of Exclusion: Repression in the Nazi State, 1933-1939,” in Caplan, Nazi Germany, 138.

55 Weinberg, “Foreign Policy in Peace and War,” 202. Doenecke and Wilz, From Isolation to War, 82.

56 Weinberg, “Foreign Policy in Peace and War,” 202-03. Merriman, A History of Modern Europe, 1034-35.

57 Weinberg, “Foreign Policy in Peace and War,” 207-08. Merriman, A History of Modern Europe, 1051-52.

58 Merriman, A History of Modern Europe, 1051-55.

59 Doenecke and Wilz, From Isolation to War, 108. Merriman, A History of Modern Europe, 1053. Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 513.

60 Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 419.

61 Merriman, A History of Modern Europe, 1055-56. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 422.

62 Merriman, A History of Modern Europe, 1056-58. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 425.

63 Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 432-34. Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 518.

64 Doenecke and Wilz, From Isolation to War, 120. Merriman, A History of Modern Europe, 1060-61.

65 Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 438. Merriman, A History of Modern Europe, 1061-62.

66 Doenecke and Wilz, From Isolation to War, 123-24. Merriman, A History of Modern Europe, 1062-63.

67 “The German ‘Lightning War’ Strategy in the Second World War,” Imperial War Museums, accessed March 8, 2024, https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/the-german-lightning-war-strategy-of-the-second-world-war. John F. Kreis, “Blitzkrieg in Poland,” Air Power History 36, no. 3 (1989), 32.

68 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 517. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 413.

69 Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 410, 413-18. Doenecke and Wilz, From Isolation to War, 113.

70 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 520.

71 Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 441.

72 Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 445, 449. Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 520.

73 Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 454-55.

74 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 520. Doenecke and Wilz, From Isolation to War, 136.

75 “Lindbergh Accuses Jews of Pushing U.S. to War,” Jewish Virtual Library, accessed, March 9, 2024, https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/lindbergh-accuses-jews-of-pushing-u-s-to-war.

76 Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 433, 433n.

77 Merriman, A History of Modern Europe, 1063-64. Doenecke and Wilz, From Isolation to War, 128.

78 Doenecke and Wilz, From Isolation to War, 131-32.

79 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 522-23.

80 Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 452. Merriman, A History of Modern Europe, 1064.

81 Doenecke and Wilz, From Isolation to War, 124-26. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 459.

82 Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 452. Merriman, A History of Modern Europe, 1064. Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 523.

83 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 524-25. Doenecke and Wilz, From Isolation to War, 144.

84 Doenecke and Wilz, From Isolation to War, 152.

85 Doenecke and Wilz, From Isolation to War, 145-46.

86 Merriman, A History of Modern Europe, 1068-69.

87 Timothy Snyder, Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin, 2nd ed. (New York: Basic Books, 2022), 175, 184, 189, 221-22.

88 Merriman, A History of Modern Europe, 1069. “Mass Shooting of Jews During the Holocaust,” Holocaust Encyclopedia, last edited August 31, 2021, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/mass-shootings-of-jews-during-the-holocaust.

89 Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 484.

90 Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 503.

91 Doenecke and Wilz, From Isolation to War, 171. Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 530.

92 Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 505.

93 Doenecke and Wilz, From Isolation to War, 163-65, 173.

94 Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 508-10. Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 534.

95 Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 512-13.

96 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 534-35.

97 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 534-35. Doenecke and Wilz, From Isolation to War, 215-18. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 519. “Pearl Harbor Attack,” Britannica, last updated April 15, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/event/Pearl-Harbor-attack/The-attack.

98 “Joint Address to Congress Leading to a Declaration of War Against Japan (1941),” National Archives, last modified February 8, 2022, https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/joint-address-to-congress-declaration-of-war-against-japan.

99 Herring, From Colony to Superpower, 535.